Regeneration, as a concept, draws on ideas of rebirth, restoration, and revival. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the frenzy of urban regeneration projects in the western world is undertaken, according to Saskia Sassen, in direct pursuit of “global city” status, where the signature of the global city arises from global branding by urban regeneration.[1] Two major features of the wave of regeneration projects of that period are the active incorporation of community consultation within flagship cultural projects focused on physical transformation of place, and policies of producing and controlling positive perceptions of planning, process, and outcomes. If Sassen’s argument is valid, then Dublin, Ireland, pursued global city status aggressively from the early 1990s, with a number of large-scale urban regeneration projects—Temple Bar, the Docklands, and Ballymun—transforming the city’s center and its most marginalized suburb. The regeneration of bricks and mortar can be easily planned, measured, and evaluated, but the regeneration of a people’s psyche—a repositioning, perhaps, of an identity—requires a more fully humane approach. It is this human imperative which prompted the integration of the arts into urban regeneration program.

The axis theater, in the center of Ballymun, Dublin, was established as a direct result of the largest urban regeneration project (ongoing since 1998) ever to have taken place in the Republic of Ireland. As the centerpiece of its response to the regeneration, axis staged From These Green Heights (2004) by the Dublin-born playwright, Dermot Bolger, which would become the first play of his The Ballymun Trilogy, followed by The Townlands of Brazil in 2006 and The Consequences of Lighting in 2008. During one performance of From These Green Heights, a recovering drug addict, either unfamiliar with, or ignoring theater etiquette, wandered around the auditorium, shouting at the actors onstage, “Oh Jesus, I can’t take this.” The actors delivered a polished production, and the man in the auditorium improvised, speaking out of an intense personal encounter with a play in performance; the fictional portrayal of Ballymun’s heroin economy struck him, almost literally. This incident opens up questions of Bolger’s Trilogy as a form of playing witness: what are the active levels and layers of involvement, perception, and testimony concerned in bringing the plays to the stage, and afterwards? These questions, in Ballymun, parallel the ethical and human contexts in which the regeneration itself takes place.

This paper will use the notion of playing witness to reflect on the experience of regeneration in the stigmatized, predominantly working-class community of Ballymun. Theater’s effects will be explored by examining how the art form offered a platform to the community to collectively remember the past, and embrace the future. Susan Bennett’s “web of interpretation,”—the name I have given to Bennett’s ideas about theatrical production and reception presented in her influential Theatre Audiences (1990)—offers a conceptual frame in which moments of witness and layers of interpretation can be explored, with particular reference to three key witnesses: the dramatist (as it pertains to this article, Bolger), a local actor (Kelly Hickey), and an outside audience member (myself). The way in which the work of axis, especially in relation to Bolger’s Trilogy, questions established ideas of community theater will be considered with reference to Raymond Williams’ theory of the “dominant, the residual, and the emergent.”[2] Established understandings of community theater struggle to account for a new—emerging—form, which this researcher will argue exposes limitations among accepted ways of categorizing theater of this kind.

Ballymun’s Story

The cornerstone of the Ballymun Estate was laid in 1966 as a powerful signal to the rest of Europe that Ireland was embracing modernity by implementing the most ambitious large-scale, high-rise modern housing scheme ever in the history of the state. The estate would be located on the north side of Dublin city, five miles from the city center and two miles from the capital’s airport. The creation of Ballymun was a knee-jerk reaction by the then Minister for State, Neil Blaney, to the inner-city housing crisis that escalated in the early 1960s when four people lost their lives when tenement buildings collapsed into the street. This new high-rise estate would house up to 20,000 people in what the city council envisaged as a self-contained community, supported by an array of social amenities.[3] However, in reality, the majority of services and local amenities that decorated the blueprint never materialized. This failure, together with spatial isolation due to poor transport links, economic exclusion, and aesthetically bankrupt design, combined to produce the largest impoverished urban estate in Ireland.[4] By the mid-1980s Ballymun had become known as a ghetto, where widespread drug abuse and anti-social behaviour was rife.[5] The first progressive step by the Irish government in responding to the Ballymun crisis was the implementation of a “refurbishment programme” in 1993, which attempted to renew part of the estate.[6] This “refurbishment programme” was discontinued, following review, in favor of a more ambitious and all-encompassing regeneration strategy (ongoing since 1998), which Ballymun Regeneration Ltd. (BRL) was set up to oversee. The regeneration project is now sixteen years in process, and, because the first ten years of activity coincided with Ireland’s surge of economic growth—in other words, the Celtic tiger era—significant progress was made, as is especially evident in the physical environment of the area, from the quality of residential homes to the development of a new main street.

The social amenities that were all but jettisoned in the first build of Ballymun were top of the agenda for the regeneration of the area: “There was a sense of righting a wrong.”[7]One of the most significant outcomes of this approach was the building of the axis Arts and Community Resource Centre at the very heart of the town, for which the facility and its work was embraced as the centerpiece of the regeneration project. As articulated by the Ballymun Regeneration Progress Report, 2005-2006,

The axis Arts and Community Resource Centre was the flagship building of the regeneration. axis’ key stakeholders are the residents of Ballymun, artists resident in the community, the professional Arts sector, the community and voluntary sector and the local authority. In its dual role as an Arts and Community Resource Centre, axishas gained national recognition for its unique programming that places local people and their stories and creativity at the centre of works of the highest standard.[8]

The defining character of axis as a center that places local people, their stories, and creativity at the hub of their programming decisions is nowhere more apparent than in the decision it took to commission and stage The Ballymun Trilogy (2004-2008), under the directorship of Ray Yeates.

In the summer of 2004, Dermot Bolger was commissioned to write a poem to be recited at the Public Wake for the demolition of the first tower block. The poem, “Ballymun Incantation,” is a sustained reflection on the lives and experiences of a variety of local people across the course of Ballymun’s initial build, through the years of decline, and into the eventual regeneration. The poem was recited publicly by a mix of professional actors and local performers, an approach to casting that would continue with The Ballymun Trilogy. The poem’s final lines, reprinted in the text of his trilogy, read:

Every young poet who wrote it out in verse:

McDonagh and McDermott, Connolly and Pearse,

Every name scrawled on walls in each tower block,

Every face that is remembered, every face forgot,

Every life that ended here and every life begun:

The living and the dead of Ballymun.[9]

The poem is a homage to the many voices that were never heard, and a memorial to broken promises and suffering endured by the local community; it was, in this way, directly relevant to the majority of the audience. Its impact was twofold: first, it generated such a strong local response that following the Public Wake, Bolger returned by public demand to read the poem himself to an audience of 5,000 people the next day; and second, it spurred axis to commission the poet—now transformed, as it were, into a medium for the voice of the community—to write a play based on the poem, From These Green Heights. Following extraordinary local responses to From These Green Heights, axis commissioned The Townlands of Brazil (2006) and The Consequences of Lightning (2008), thus completing the Ballymun Trilogy. The dramatic action of each play centers on the lives and experiences of members of the Ballymun community. At the core of each drama is a series of interlocking lives which play out in dramas of family, home, place, and identity.

Bolger’s Approach to the Project

In writing the trilogy, Dermot Bolger was particularly conscious of his status as an outside artist taking on the responsibility of speaking on behalf of a community to which he had no ancestral link. He was born in the neighboring district of Finglas, and his relationship with Ballymun started in 1979, when he gave a poetry reading in the basement of a tower block. Ballymun, however, has been a constant figure in his work in the years since then, featuring in many of his novels, plays, and poems.[10] In conversation with this researcher, he acknowledged his enthusiasm at the opportunity to write for Ballymun, as the place embraced its new status as Ireland’s largest urban regeneration zone. According to Bolger, the commission to write From These Green Heights was the kind of privilege that few playwrights are offered, because “you don’t always get a chance, short of using TV, of communicating directly with the people your plays are written for.”[11] Bolger was very conscious of the fact that he was producing a piece of work (what was ultimately to become a body of work in The Trilogy) knowing “where it was going to be staged, and it was a slightly different audience going to it, going to see it.”[12] The specificity of the narrative in terms of place and people meant that Bolger was very much aware of the risk of limiting the play by overemphasizing local experience and the performance conditions in the fabric of the work. The task, he described, is to avoid “making a piece of work that is so site-specific that it can’t be played on or be played anywhere else,” and there was what he described as a feeling of “pressure as a playwright [in] trying to create a piece of theater that is true to Ballymun” and also commands attention as a piece of dramatic art.[13]

On the challenge of creating a play about a community he was not part of, Bolger acknowledged the need to research the historical and social aspects of the area but emphasized the importance of taking on the role of a witness capable of understanding and depicting the lives of people he knew, and had heard of, from the area. When asked about the ethics of such a project, and the obligation to accurately represent those people, Bolger was quick to clarify that in fact, while his understanding and depiction of the people of Ballymun was based on real life characters, he only used aspects of their personalities or their personal stories to inform his own original fictional/historical storyline. As he remarked,

[T]hat’s research, but without interviewing people directly. If you do that you feel you have a burden to tell their story exactly and it limits you. You feel a certain conscience, so you almost want to get the facts right. You want to get the actual period right and then you really want to invent characters, and then you don’t want to be burdened by saying I misrepresented that man I spoke to last week. I mean, again, I would never go into who a character is based on, but there are two or three stories that I would have known that would have formed that play and that some have links to Ballymun, and that’s the bit the playwright keeps back. Even though the people may have heard about the story, they wouldn’t know how it was about them.[14]

Bolger was also writing in the shadow of the media’s not-altogether flattering representations of Ballymun. Lynn Connolly emphasizes the role the media played in demonizing Ballymun as a community, thus contributing to the potent stigma that would become attached to the area and embed itself in the national consciousness: “The media never let go of Ballymun for a minute, and it was a rare day when a good story was printed about the estate. The Evening Press and the Evening Herald constantly reported crimes that happened in Ballymun.”[15] Similarly, Ballymun resident D. O’Sullivan spoke to this researcher about the media’s central role in cementing Ballymun’s national image as that of a ghetto, remarking that “The media love to portray Ballymun in a negative way and class it as a lower class town.”[16] Bolger was very aware how Ballymun had been misrepresented in the past in other aesthetic media such as TV, film, novels, and the like. He was conscious not to follow suit but instead to create plays that were true to the lives of the community, without romanticizing or glamorizing the community’s past and instead developing a style of dramatic storytelling that gave the authority of first-hand testimony to the fictionalized characters.

Issues of representation, especially on behalf of “the other,” are always problematic and have generated much theoretical debate, particularly among feminist critics. Tim Prentki and Shiela Preston, in their edited collection The Applied Theatre Reader (2009), have emphasized the dangers of representation, with special regard for those cultural workers who are active in constructing meaningful representations that may not ultimately be reflective of, or beneficial to, the community in question. This is a pressing concern for the whole field of applied drama, and it is particularly relevant for Bolger and his representation of life in a marginalized community traduced as a drug-fuelled vertical ghetto in the public imagination. As Preston writes, “representations [that] depict the real lives of individuals or groups who may be vulnerable and/or marginalised from the dominant hegemony is an ethical as well as political concern.”[17] She goes on to suggest that one approach to potentially counteract the potency of misrepresentation is that of generating the means of production from within the community. This is where the axis Arts and Community Resource Centre assumes critical importance. The center was initiated by the hard work of a community united by hardship, one which recognized the importance of the provision of arts facilities for their own collective nourishment; importantly, it was not the brainchild of BRL or the Regeneration Masterplan. The community itself secured initial funding for the center by competing for EU funds, and by other agencies attaching themselves to the project at a later stage, in supporting roles. The generation, so to speak, of axis through the community’s will and dedication—and not as an initiative parachuted in to serve an outsider’s vision for the area—gives to the center’s heightened sense of local popular ownership of artistic creation within its walls.

Bolger also spoke to this researcher about how writing these plays for a relatively new community theater venue offered him greater artistic licence, a poetic freedom that is seldom guaranteed with commissions for mainstream theater. He emphasized the unique demands involved in writing the Trilogy, including the need both to write plays for a mixed cast of professional actors and local amateurs, and to write into the actual space that was also embedded in the stage action as the fictional location of the dramas. Bolger’s insistence from the outset was that, while the plays would be professionally produced, he wanted certain parts to be performed by local people, who would be the real voice of the community onstage. This was (and is) a somewhat revolutionary move in terms of Irish professional theater practices. Kelly Hickey—whose importance to this paper will become clear shortly—was one of the youngest among a group of local amateur actors given an opportunity to work alongside established professional actors, such as Vinnie McCabe and Brendan Laird. From the very beginning, Bolger was also conscious that the people of Ballymun “didn’t want anything whitewashed of Ballymun, but they also didn’t want that it was all a disaster because there was a lot of great happiness in Ballymun.”[18] How such considerations were balanced becomes apparent in the following brief overview of the plays.

The Ballymun Trilogy (2004-2008)

The dramatic plot for each of the plays in The Ballymun Trilogy presents a complex web of local personal narratives and commentaries on lives lived and lost in the Ballymun Estate. Subjects of place, belonging, identity, family, and community are central to all the plays.

From These Green Heights stages Christy, Carmel, and their son, Dessie, relocated from Gardiner Street among the original, select group of tenants. Dessie’s relationship with Marie brings the family into contact with Marie’s mother, Jane, and her sister, Sharon. Jane has moved to Ballymun with her girls from the refined neighboring suburb of Glasnevin, following the breakup of her marriage. The twists and turns of Dessie and Marie’s relationship over many years link the families’ histories, and their own daughter, Tara, born in Ballymun, embodies and anticipates a better future at the play’s end.

The Townlands of Brazil stages the tragic history of Eileen, a tailor’s daughter, rejected by her parents when she became pregnant by Michael, a manual labourer from a small cottage in rural Ballymun in 1963. Eileen escaped to England, and raised Matthew alone as Michael had been killed in a construction accident while waiting for her to join him. Matthew arrives in Ballymun as a grown man, an engineer working on the demolition of the Ballymun tower blocks. The place he enters was the site of the home to which his mother could never return; it is now home to Monika, a young Polish woman among many immigrants to a prosperous Ireland, who will encounter a tragedy of her own in contemporary Ballymun.

The Consequences of Lightning takes place around the funeral of Sam, the original Ballymun tenant, the first to resettle in the new housing project. His son, Frank, who had a past relationship with Katie, is a successful developer living in middle-class comfort in fashionable Malahide. Sam is mourned by the immature Jeepers, and Katie’s daughter, Annie. Martin, one of a small community of Jesuit fathers who opted to live in Ballymun, mediates the complex unfinished business of the people assembled for Sam’s burial. Sam’s ghost is present throughout, commenting on place, people, and events.

These summaries reveal the central role of local narratives in the dramas of the Trilogy, narratives drawing on Ballymun’s painful past, its fluid, contradictory present, and its uncertain future. The dramatization of such stories within the purpose-built community theater and intended for a predominantly local audience poses questions about the interconnected layers of involvement and interpretation in acts of dramatic representation. Broadly speaking, in terms of involvement, this article explores three distinct roles: first, that of Dermot Bolger, whose involvement in the project as the creator of the original work is, of course, fundamental to the realization of the theater events; second, that of the aforementioned Kelly Hickey, a local amateur actor selected to represent her own community onstage, whose involvement challenges conventions of ownership of representation and dramatic material; and third, that of Niamh Malone (this researcher), whose involvement consists of having, so to speak, no direct involvement, who is an audience member, outside of and with no prior personal link to the community of Ballymun. This essay draws on the cumulative effect of all three witness positions to enable a thick description of the nature and significance of The Trilogy for the community of Ballymun.

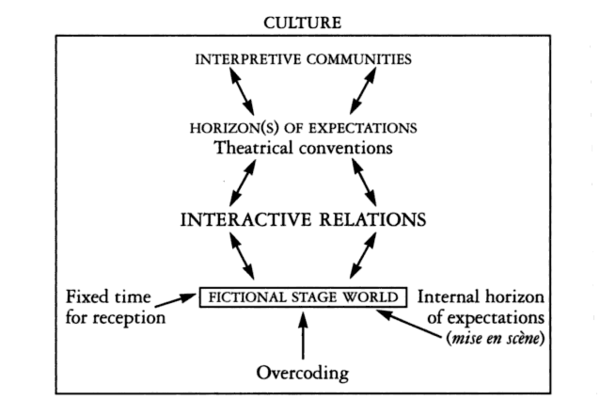

The central ideas around theatrical production and reception that inform Susan Bennett’s Theatre Audiences—what this author is calling her “web of interpretation”—offer a framework for understanding the complex layers of cultural forces in play in acts of theater. Bennett stresses the importance of the sensitivity of the witness to the social environment in which the play is set, and the cultural lens through which acts of interpretation will be perceived, especially from within the diversity of the auditorium. She argues for

the necessity to view the theatrical event beyond its immediate conditions and to foreground its social constitution. The description of an individual response to a particular production may not be possible or, indeed, even desirable. But, because of that individual’s participation in a given culture and the importance of his/her culturally-constituted horizon of expectations, and selection of a particular social event, it is important to reposition the study of drama to reflect this.[19]

Bennett summarizes this complex web of interpretation in the following diagram:[20]

Figure 1.1 Culture and Interactive Relations

While a comprehensive explication of Bennett’s diagram is beyond the purview of this article, the author wishes to highlight certain aspects of it that particularly pertain to the conclusions of this paper. To be sure, Bennett’s web of interpretation suggests that the three witnesses considered here—Bolger, Hickey, and Malone—all approach Ballymun, as it actually exists and as it is represented in the Trilogy, from distinct positions in relation to the creative processes of representation and interpretation. All three emerge from specific and different “interpretive communities.” However, there are significant overlaps among the experiences by which their cultural lenses have been formed. Firstly, all are involved in the art form of drama, Bolger as an internationally acclaimed professional playwright, Hickey as a local person born and reared in Ballymun with a background in youth theater, and Malone as a theater studies academic. Secondly, all three witnesses are from Irish working-class backgrounds. Third and finally, they have all lived in Dublin city. Such overlap in lived experiences suggests that cultural codes will produce significant degrees of shared meanings for the three witnesses. Coupled with the “Horizons of Expectation,” according to which Bolger, Hickey, and Malone could be said to be determined by their prescribed roles within the creative process—author, actor, and audience, respectively—Bennett’s web of interpretation clearly demonstrates the means by which specific expectations and perspectives influence and inform acts of witnessing.

What is particularly interesting about The Ballymun Trilogy in relation to “expectations” and “theatrical conventions” is that the form of dramatic expression developed by Bolger challenges influential understandings and categorizations of “community theater” on a number of fronts. While “community theater” in recent years has been configured as a key practice of the applied theater field,[21] it is generally accepted to be a form of theater which is produced for, by, or with a community outside mainstream theatrical venues and for a targeted audience.[22] According to such a definition, it could be argued that Bolger’s work is indeed “community theater” as it was made specifically for the community of Ballymun; however, the Trilogy challenges the category in that it was produced in a professional theater venue, with a professional production team, and performed by a cast of—in the main—professional actors. Additionally, the fact that Bolger, an established international artist, wrote on behalf of the community runs against established practices within the field of community drama, where scripts typically emerge from facilitated community workshops. Bolger’s approach to the creative project could therefore be seen as an emergent popular theater form, retaining remnants of the principles of an older form, such as writing for a community and having amateur actors perform. While established forms of community theater exist “dominantly,” the approach to writing and producing the Trilogy, not to mention the success it found, may indicate the emergence of a new cultural form.

Such a development in practice follows the dynamic process of cultural change described by Raymond Williams.[23] In what he refers to as an “epochal analysis,” Williams suggests that once a cultural process is established, it in turn becomes a cultural system, which will ultimately reveal “determinate dominant features.” The dominant and its characteristics can only be fully appreciated with reference to “residual” and “emergent” cultural features. Williams’s use of the “residual”—those aspects of the former “dominant”—as opposed to that of the “past” is a clear acknowledgement of the power of past systems of action and thought to continue to influence the present. The idea of an “emergent” acknowledges the inevitable generation of new meanings, values, and practices, within a dominant cultural system. In the case of Bolger’s work, his intense engagement with the living community of Ballymun, at a moment of extraordinary change, seems to have been the factor which set the emergent in motion.

The two plays subsequent to From These Green Heights were presented to an audience whose horizons of expectations had been shaped by their experiences of witnessing the first play of The Trilogy. The realization of the first play, in form, application, and reception, works towards shaping what Prentki and Preston refer to as “the poetics of applied theatre.”[24] Once the first play in its entirety has been performed, interpreted, and received by the audience of the axis theater, then Bolger’s work could be said to have set in motion a “poetics of community theater” which accommodates the multiple layers of interpretation to which Bennett alludes. Bennett’s work is especially helpful given her understanding that “the feedback of non-traditional audiences has changed, above all else, the product we recognise as theatre.”[25] In addition, Bennett’s “interactive relations” revolve around meanings produced in the encounter with the “fictional stage world” (see the figure above). There is not enough space here to venture into the vast field of semiotics and related areas of scholarship that inform Bennett’s, and my, work, so it must suffice here to note that the three identified witnesses—Bolger, Hickey, and Malone—arrive at meaning again from positions shaped by their roles within and/or in relationship to the creative process. For Bolger, then, the fictional worlds of the plays are created not so much through the limitations imposed by a “fixed time for perception” (see, again, the figure above); rather, dramatic content is distilled from cumulative encounters with narrative memories of the people and place of Ballymun over his lifetime. Once he was commissioned to write the plays, he could draw from that reservoir of knowledge to inform each dramatic narrative. The playwright’s “internal horizon of expectations” emerge in the dense, poetic style he brings to these memory plays, shaping in turn the mise en scène which frames the dramatic action.

For Hickey, for whom the fictional stage world reflected a degree of lived reality, her experience of the plays is not principally a function of performance duration but instead develops through reflection on her own lived experiences of growing up in Ballymun, prompted and organized by Bolger’s dramaturgy. As a local girl, her formative years were spent living through the transition from a high-rise flat in the old Ballymun to a semi-detached house on a small estate in the new Ballymun. She told this researcher that, like many “native subjects,” she was conscious of the “burden” of representing her community and speaking on behalf of her own people, who were not slow to offer (overwhelmingly positive) feedback on her role in The Townlands of Brazil. She remarked that,

A lot of people felt that it was their story being told and were really happy about how they have been depicted. People found the contrast of the tough times the Irish went through in the 1960s is reflective of what the local Polish population in Ballymun are going through now, and therefore challenging to stereotypes. As the character of Eileen, I got a lot of responses particularly from older ladies because they identified with the plight of my character who had to go to England to have the baby and escape the nuns.[26]

This remark suggests that her presence in the community enabled the questions posed by the play to continue to be pondered after the performance event.

For the third named witness, Malone (this researcher), the fictional stage world offered both a potted history of the area’s people and an insight into the human cost of the demise of the Ballymun estate during the late 1970s and 80s, the effect of which was to sharpen the sense of the impact of a human regeneration mirrored in the physical renewal—a renaissance of the people and their collective sense of self-belief. The formation of my perception took place across the duration of the plays’ performances and was later developed by further research. As a member of the audience in an auditorium filled primarily with local people, I had certain expectations of what I understood to be a recognizable community theater event, which, following my act of witness, I was obliged to revisit. As this essay’s title suggests, I was especially struck by the improvised interactions with actors initiated by audience members, as the style of the plays would suggest that this was neither foreseen nor intended by the author. Brendan Laird, who took lead roles in The Townlands of Brazil and The Consequences of Lightning, comments on how established audience conventions were challenged by local people:

There were instances during the run of Consequences where some of the audience (specifically, the Shangan Ladies’ Club) would comment as I was making an entrance: “Ah, here he is again: Moneybags.” When I was trying to “get back” with my ex (played by Anne O'Neill) in another scene, the audience (again, women) would freely comment with things like, “She doesn't want anything to do with him,” etc.[27]

Active, vocal responses such as this, along with those witnessed by this author in the axis theater in Ballymun on the opening nights of all three plays of The Ballymun Trilogy, testify clearly to the importance of immediacy and localism to working-class audiences. The exclamation, “Ah Jesus, I can’t take this,” spoken by a man no longer able to remain passive in the face of the representation of an all-too-recognizable reality suggests that the effect of Bolger’s dramatic narrative and mise en scène goes beyond giving local people an opportunity to witness their own community’s story unfold through dramatic narrative. Rather, Bolger’s work implicitly invites the Ballymun audience to interpret the representation of their people and their area as it is seen through the eyes of the playwright and artistic team of director, designer, and actors. The unscripted interaction between audience and stage demonstrates the potential for effect generated by a play that stages narratives drawn directly from community experience and is performed in a dedicated local space.

As an outsider, my interpretation of the plays was most definitely informed by how the people around me in the auditorium were reacting to the action unfolding. The response from local people, recorded both in observation records and in formal documents such as theater reviews, testify to the power of good theater. Generally, local people were very positive about the plays, with comments such as those offered by Ballymun resident N. Hanaphy being typical of many:

I really enjoyed the plays. I went with friends, and all of them were happy with how Ballymun was represented. […] I learned a lot about the history of Ballymun through Townlands in particular. It was really important that it wasn’t just about the people from Ballymun but also the people who have moved into our area.[28]

Considered alongside Hickey’s account of audience comments given directly to her, Hanaphy points to the plays’ success in making the area’s changing present, as well as its past, a topic for people’s reflection.

Dermot Bolger describes himself as greatly privileged to have had the opportunity to bear witness to the stories of his near neighbours in Ballymun; Kelly Hickey experienced no less a privilege in embodying and enacting those stories for her own community. My own research project was stimulated by the experience of witnessing a privileged audience responding to their work over three first nights in the axis theater—that community’s shared space, dedicated to representation and interpretation. Bennett’s “web of interpretation” offers a useful framework through which to consider and reflect on multiple, related, but always distinctive witness positions, and to open up the complexity of how meaning is constructed and authorized in a creative exchange in which local audiences witness artists bearing witness to them.

[1]Saskia Sassen, The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo, 2nd ed. (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[2]See Williams’ essay in K.M. Newton, ed., Twentieth-Century Literary Theory: a Reader (London: Macmillan, 1998), 242.

[3]See Sinéad Power, “The Development of the Ballymun Housing Scheme, Dublin 1965-1969,” Irish Geography 33, no. 2 (2000): 199-212.

[4]This information originally derives in part from Michelle Norris, “Privatising Public Housing Estate Regeneration: A Case Study of Ballymun Regeneration Ltd, Dublin” (paper presented at the Irish Social Policy Association/Social Policy Association Conference: “Development, Regeneration and Social Policy,” Trinity College Dublin, July 26-28,2001). A version of this paper can be found at “Irish Social Policy Association: Annual Conference 2001,” http://www.ispa.ie/newsevents/2001conference/. Much of this information was also gathered from Jenny Muir, “The Representation of Local Interests in Area-Based Urban Regeneration Programmes” (paper presented at the Housing Studies Association Conference, University of Bristol, September 9-10, 2003).

[5]See Lynn Connolly, The Mun: Growing Up in Ballymun (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 2006).

[6] As learned from Frank Wassenberg, “Housing in an Expanding Europe: theory, policy, participation and implementation,” (paper presented at European Network for Housing Research International Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, July 2-5, 2006).

[7]Council Representative and Senior Planner for Ballymun Regeneration Ltd., recorded communication with the author, 2008.

[8]Ballymun Regeneration Ltd, Ballymun Regeneration Progress Report, 2005-2006, accessed July 8, 2008, http://www.brl.ie/pdf/Monitoring_Report_2005_2006_web.pdf.

[9] Dermot Bolger, The Ballymun Trilogy (Dublin: New Island, 2010), xxi.

[10]See his extensive catalogue of published and current works and projects at www.dermotbolger.com.

[11]Dermot Bolger, recorded communication with the author, 2008.

[12]Ibid.

[13]Ibid.

[14]Ibid.

[15]Connolly, The Mun, 117.

[16]D. O’Sullvan (local resident of Ballymun), recorded communication with the author, 2011. Full names of several interviewees have not been disclosed for the purposes of anonymity.

[17]Shiela Preston, “Introduction to Ethics of Representation,” in The Applied Theatre Reader, eds. Tim Prentki and Shiela Preston (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2009), 65.

[18]Bolger, recorded communication.

[19] Susan Bennett,Theatre Audiences: A Theory of Production and Reception (London: Routledge, 1990), 184. The emphasis is in the original.

[20]Ibid., 183.

[21] Alongside drama/theater in education and theater of the political left; see Helen Nicholson,Applied Drama: The Gift of Theatre (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

[22]See Prentki and Preston, ed. Applied Theatre Reader.

[23] See Newton, ed. Twentieth-Century Literary Theory, 242.

[24]See Prentki’s discussion of “poetics” as it relates to applied theater in his “Introduction to Poetics of Representation,” in The Applied Theory Reader, eds. Tim Prentki and Shiela Preston (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2009), 19-21. His essay opens the second section of the edited collection titled “Poetics of Representation.”

[25]Bennett, Theatre Audiences, 182.

[26]Kelly Hickey (local actor from Ballymun), recorded communication with the author, 2009.

[27]Brendan Laird (professional actor), recorded communication with the author, 2011.

[28]N. Hanaphy, (local resident of Ballymun), recorded communication with the author, 2010.