Theatrical performances can enact two different forms of narrative—familiarizing or de-familiarizing—alternately confirming audiences in their sense of comfortably secure identity or provoking them to question that security. In presenting a de-familiarizing narrative or performance, theater makes the audience look and reflect anew. This has been a particularly powerful strategy within Irish culture since the revelations of institutional abuse have forced a re-investigation of the past, and a questioning, at a collective level, of assumptions about Irish identity, which are founded upon that past. The three works this essay discusses—The Walworth Farce (2006) by Enda Walsh, The Blue Boy (2011) by Brokentalkers, and Laundry (2011) by ANU Productions—mirror shifts within Irish culture and society, reflecting a profound destabilizing of the security of the conjoined issues of the past and identity. Their performance strategies are thus speaking out of cultural upheaval, as well as speaking back to that culture. And by using a combination of familiarizing and de-familiarizing narratives, these three productions posit the need for a culture of active spectatorship that can reflect on the specific question of how Irish theater interacts with the past—both on local and national levels—and with more general issues of theater-as-memory.

In The Walworth Farce, Enda Walsh creates a high-octane version of a dysfunctional family whose defining activity is the daily re-enactment of a re-invented version of their past. The three central characters—Dinny and his sons Sean and Blake—are Irish emigrants living in an impoverished council flat in London’s Elephant and Castle. The men live on the fifteenth floor of the block, which does not have a lift, a fact that emphasizes their isolation from “normal” society. Each day the three men deliberately and self-consciously perform a play in which they re-enact their mythical last day in Ireland. Elements of this play are based on real life: the death of Dinny’s mother, and Dinny’s subsequent murder of his brother and sister-in-law. But these facts are buried in a much embroidered and fantastic tale involving another family and much skullduggery, money-grabbing, and wife-swapping.

The audience is given insight into how this unlikely plot has been devised when, at some moments in the performance, new lines are added to what is clearly an ever-evolving script.[1] As the audience piece together this evolution, it becomes clear that Blake and Sean, though now adult men, have been performing their roles since they were children, acting out the parts of “Young Blake” and “Young Sean,” as well as playing the parts of their uncle, aunt, and mother (among others). This is not simply a parodic version of a play within a play, but a parody of the idea of “playing” itself. Childhood games of make-believe and role-playing clearly fuel the two boys’ engagement with this performance (seen, for example, in the manic glee of Blake’s wig-switching, and Sean’s diving in and out of wardrobes), though they become grotesque in this adult and adulterated version of childhood mimicry. The performances of Young Blake and Young Sean do not, however, create a space of innocence within the play. Young Blake and Young Sean recount how they beat up and taunt a neighbourhood boy, and how they impaled a dog on a tent pole.[2] These two stories are invented for the sake of the performance, something the audience later realizes after Sean reveals that in the “real” past he and Blake quietly played in the garden and planned to become astronauts and bus drivers when they grew up.[3] While Dinny’s acts of imagined violence in the family performance do have roots in reality, the boys’ imagined acts do not. By changing these facts and reimagining the two boys as violent bullies, Dinny—as ring-leader and originator of the story—has recreated them in his own image. This act not only robs the two boys of their childhood but also implicates them in the overall violence of the performance and, in doing so, arrests any possibility for them to imagine their way out of the performance. Though Sean remembers what really happened—he recounts his childhood memory of that day—and urges Blake to escape with him, Blake was too young to remember and has no other basis for his identity than Dinny’s warped version of the past. Hence, when Blake realizes the emptiness of Dinny’s world and finally sees the need for escape, he can only imagine and enact that escape in violent terms, first by killing Dinny and then tricking Sean into killing him, his own brother.

What makes this day different to all the other days that the three men have performed their farce is that Sean has unwittingly made a friend in Hayley, a checkout girl at the local Tesco: when Sean accidentally brings the wrong grocery bag home, Hayley generously delivers the right bag to him. Hayley’s entrance disrupts the performance by introducing a note of reality, as has been noted by several commentators.[4] What Hayley also introduces, of course, is time. The men’s daily repetition of the past through performance attempts to freeze their past in a farcical non-time so that neither change nor the lack of change needs to be admitted. Hayley, a representative not just of the real outside world but of linear time, forces the idea of change and progress into the narrative. Hayley says that she can only stay for the duration of her lunch break and suggests to Sean that they might go to Brighton Beach at the weekend or “sometime.”[5] These suggestions introduce a sense of futurity to the flat, which is otherwise remarkably successfully frozen in time (albeit the past is not “real” but invented). Dinny refuses to allow any disintegration within the performed “memory”; the story of the past must remain vivid, complete, and unquestioned. Though new lines may be added to the script, the freezing of time insists that no new memories can be formed. The challenge and burden of this insistence is clearly shown in the eroding familial relationships but perhaps is most visible in the moment when Dinny smears moisturizing cream on Hayley’s face, forcing her into a performance of white face. Hayley’s newness, visually obvious in her black skin, is one challenge too far for the power of Dinny’s imagination to support such a static performance of the past.

The role of the past—even an almost entirely imagined one—in shoring up identity is vividly demonstrated in this farce; so, too, are the problems with using the past, which can only ever be reconstructed and never re-lived, as a basis for identity. If the past is insecure—which it inevitably is in any act of memory, and it most certainly is when the memory is in large part invented—then identity is also insecure. The manic performance and re-performance of the family farce, the inability to cope with divergences from its central form, are reactions to this insecurity. In these ways, Walsh’s play stages the relationship between memory and identity. Equally importantly, The Walworth Farce stages how memory itself functions not as a simple act of retrieval but as a creative process. Indeed, the fictional nature of the family’s daily performance illustrates this creative aspect of memory in extremis by showing how easily the past can be moulded into a new, more pleasing form, one which suits the needs of the present. The past is reinvented in order to adequately explain and support the status quo in the present. Hayley disrupts that status quo by introducing elements of “reality” and time, and by appealing directly to Sean rather than recognizing Dinny’s authority. Dinny’s presentist logic is then further disrupted by Sean’s contradictory memory of the past; though Sean’s memory may be at least partially invented too, the dreams of a different life retrospectively projected onto his younger self (who dreamed of being a bus driver—“Just like driving a rocket ‘cept your orbit’s the Grand Parade”[6]) enable progress and drive his own narrative.

What Hayley’s presence also achieves is to make the audience look anew, for when Hayley enters the plot, the audience can begin to see the drama through her eyes, as she acts as witness to what is not just parody but abuse. When Hayley frantically calls her mother for help, she alerts the audience to the explicit danger of the situation, in which she recognizes the abusive dynamic at play that keeps Blake and Sean, and now her, trapped in this violent fantasy world. Clearly, it is not the outside world but the inside world that is the threat, a reversal of Dinny’s warnings of “them bodies from outside be banging down our door and dragging you down below,” and “feckers out there […] waiting to gobble you up.”[7]

In many ways, this moment of recognition—where the attribution of safety to the refuge of the Walworth Road flat is exposed as untrue—is also at the heart of other dramas that perform and expose abusive relationships. Though The Walworth Farce concerns a single family, in many ways it stages a form of abusive acculturation that is typical of larger institutions, and which forms the basis of two works which address Ireland’s network of industrial schools and Magdalene laundries.

The Blue Boy by Brokentalkers and Laundry by ANU Productions were both first performed at the Dublin Theatre Festival in 2011 as part of the “Behind Closed Doors” strand of the festival, which described itself as an attempt to mark the ways in which the Irish theater community addresses “often forgotten facets of Irish society” such as the history of institutional abuse.[8] Both productions meditate not only on the failures to recognize this abuse in the past but also on how the memories of the past can be reintroduced and recovered. They both thus stage, in analogous ways to Walsh, the attempt through performances of memory to make present what is rendered absent by time and forgetting.

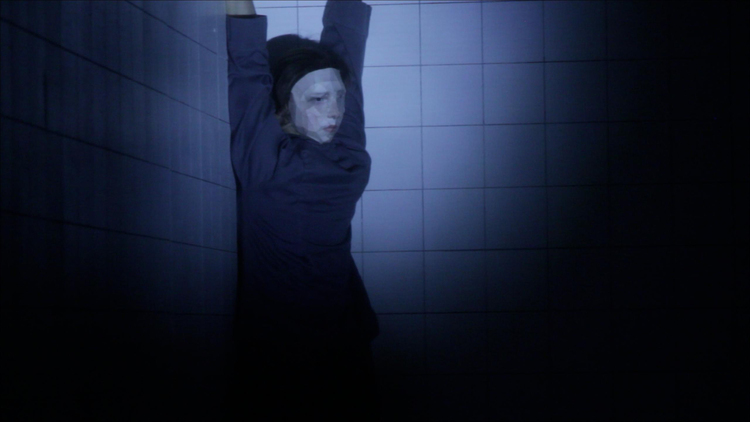

The Blue Boy is performed in a theater space but is not a traditional theater piece. Brokentalkers have devised a multi-part performance including direct address and storytelling, music, video, and audio clips, and dance. The Blue Boy is a demanding work. The theater audience is actively engaged and required to participate in the interpretation and construction of meaning. The performance consists of two main parts, and the stage is itself divided into two—a small forestage is separated by a transparent screen from the rest of the main stage. At the opening of the show, Brokentalkers co-founder Gary Keegan directly addresses the audience, describing how as a child he had played with his maternal grandfather’s yardstick, which, as Keegan had only learned in recent years, his grandfather used in his job as an undertaker. One of his grandfather’s duties was to visit Artane Industrial School to measure any child who died, in order to make a coffin for him or her. Gary pauses his story at this point and the production plays a recording of Gary’s mother describing how upset this used to make her father. He “was used to seeing adult bodies” but the children’s bodies, and the bruises he saw on them, upset him.[9] After this story, Gary walks to one side, and a projection onto the screen shows images from the 1932 Eucharistic Congress, while various recordings play, including two stories from people who had been incarcerated in industrial schools—one male, one female. At this point, the screen, opaque until now, is lit from behind so that it becomes transparent and we see seven masked performers in a dance of ritualized and repetitive tasks.

The past that The Blue Boy performs is multiple—the audience is invited into Gary’s personal memories at key points. These memories are identifiable with and yet also particular to his unique experience. When Gary shows the audience how he used to play with his grandfather’s yardstick, he provokes laughter at the incongruity of a grown man re-enacting a child’s gestures of playing with dinosaurs and guitars.[10] This sequence illustrates the role of imagination in accessing the past, as the audience must make the connection between present adult (visible) and past child (invisible). It also, of course, lulls the audience into a false sense of security, a security which begins to ebb away once Gary begins to talk of Artane. Again, here the present is in obvious tension with the past, as the twenty-first-century audience will hear Artane as a byword for institutional abuse. After the 2009 publication of the Ryan Report with its catalogue of abuses in industrial schools, the audience cannot think of Artane as a leading institution of order and reform, as it would have been thought of in Gary’s grandfather’s time. The memories evoked by the yardstick, used to measure a child’s body, are no longer surprising, yet still remain shockingly taboo.

This opposition between past and present is obvious also in the following section, where additional video footage of the 1932 Eucharistic Congress is shown, coupled with an audio soundtrack of Irish Times Religious Affairs correspondent Patsy McGarry discussing the power of the Catholic Church. Again, what is obvious here is a narrative that is formed in the present but is used to read—and to judge—the past. This is not to say that the use of these performance strategies is misleading; rather, it is to identify how they are functioning. Indeed, Brokentalkers invite the spectator to ask these kinds of questions by creating such a non-traditional show. As Gary’s narrative is a direct address to the audience, the spectator is figured as an active witness from the beginning of the piece. The shifts from story to video to audio and then to dance and music are not seamless; rather, they are abrupt and quite deliberately conspicuous.

As Gary says midway through the show, “Growing up in that neighbourhood we got a sense from our parents and grandparents that bad things had happened to the children in that place. As a child I didn’t know the details but we knew that bad things had happened on the other side of that big grey wall.”[11] Gary’s reference to the “big grey wall” is signified onstage with the screen that becomes transparent when light is cast on the “children” inside the wall. The audience’s attentive spectatorship is the kind of scrutiny that needed to be directed behind the actual institutional walls, but wasn’t.

What The Blue Boy thus performs so effectively is, like Walsh’s play, a meta-play about how memory itself functions as a creative process. The show recounts a narrative that is both familiarizing—from stories of childhood to institutionalization—and de-familiarizing—in the formal construction of the piece and in the alienation and emotional provocation of the dance performances. These dances and the accompanying music are, perhaps, the most disturbing elements of the show. Sean Millar’s music shifts between harmony and discord while the dancers are choreographed to move in repetitive and ritualized movements, evoking the cruelly repetitive nature of institutional life. The movements are erratic and shuddering, suggesting entrapment and abortive attempts at free and self-determined movement. They wear masks and one dancer is spotlit with her mask worn on the back of her head, so that the dancer’s body seems to move out of joint, against expectations. Though aesthetically this choreography is completely different to the frantic movements performed in Walsh’s play, the sense of embodied trauma and arrested development echoes between the productions. In The Blue Boy, the dance moves both enact the ritualized behavior of the past and reference the dancers’ bodies in the present, repetitively and even obsessively performing and re-performing this evocation of the past.

The multiple representational strategies of The Blue Boy foreground both the fragmented and constructed nature of memory, while also attempting to perform that memory as powerfully as possible. The visible construction of the show, from direct address to complex choreography, uses theater to mirror the artistic process implicit within the art of memory, both personal and collective. In this way, The Blue Boy is exemplary of theater-as-memory, where performance enacts memory’s bringing-into-presence what was absent.[12]

The label theater-as-memory can also be appended to ANU Productions’ Laundry, which, like The Blue Boy, attempts to bridge the temporal distance between past and present, absence and presence. Laundry is a site-specific drama performed within the former convent and laundry of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity on Sean McDermott Street in Dublin 1. The audience arrives in groups of three but are immediately separated as individual spectators and led through the building, encountering a different mini-scene in each room. The scenes include: a young man desperate to see his sister who is incarcerated in the laundry; a young woman reciting the names of the forgotten women; a young woman bathing in cold water and carbolic soap; a room of women in contorted poses reciting articles of the international conventions on human rights; an older woman who has sought refuge in the laundry following the death of her husband; a young woman who defies the strictures of the laundry and imagines herself attending a party in a new dress and heels; and finally, a young woman frantic to escape. Each of these scenes requires an act of witness or level of participation from the spectator: in the bathing scene, the audience member helps to unwrap the young woman from the bandages binding her breasts; in the escape scene, the audience member chooses whether to accept a bundle of laundry in order to help the young woman escape. This production is literally enacting theater-as-memory by blending past and present, by insisting on the presence—rather than absence—of the women who had been incarcerated in the laundry, and by mimicking some of the actions that may have occurred in the past, thereby placing the spectator in what is both a visceral and voyeuristic relationship to that past.

Laundry thus invites the audience to go beyond the walls of the convent laundry to function as active spectators of what is being performed in the present, and of the past that its performances evoke. Active spectatorship is not limited to the performance as it occurs within the laundry building; for example, after helping one woman to escape, the audience member is bundled (with an armful of laundry) into a waiting taxi, and the production’s penultimate scene is set in the taxi as the driver takes the audience member around the streets, giving a commentary on the history of the “Monto” area and the laundry within it. The final scene concludes in a modern day laundry where the audience regroups into its original three, and all three listen to an archival radio programme discussing the laundries. These two scenes concluded the production by transitioning the audience back into the outside world and providing some historical context for the scenes within the laundry building. What the taxi tour also does, of course, is to extend the role of active spectatorship from inside the building to the outside world. So the production locates the laundry firmly within a network of streets in the center of Dublin. There is no escaping the implication that the laundry is not simply an isolated and exceptional building but an embedded part of the history of the capital city itself.

The purpose of developing a culture of active spectatorship in both Laundry and The Blue Boy is to mobilize audience awareness and recognition of a much effaced past—the suffering of vulnerable children and women in institutions—with the intention of developing a more ethical collective memory, one which acknowledges the history of abuse and thus, with this knowledge, arms against future abuses. Though set in a completely different context, The Walworth Farce likewise suggests that a false version of the past can only lead to a cycle of abuse and that it is only through active and discriminating spectatorship that false, or farcical, performances of the past can be undone.

The term “ethical memory,” however, does not simply refer to the ethics of remembering but also to the ethical uses of memory. And in this context, it is necessary to discuss theater-as-memory in terms of its potentially traumatizing effect on the audience. This is most strikingly an issue for Laundry, which works to reconfigure the relationship between spectator and spectacle, particularly in scenes in which direct participation is called for.

In the bathing scene (which is often one of the first scenes encountered), the audience member helps a young woman unbind her breasts before watching as she enters a cold bath and washes herself. When she emerges out of the bath she again appeals, silently, to the audience member to help her rewrap the bandages around her breasts. When I went to see the production this was the third scene I witnessed in the show, and I was unprepared for how complicit it made me feel, as I became implicated in both the physical control and the surveillance of this young woman. Speaking to other spectators since the production, I know that my feelings of guilt and discomfort were shared, and even more strongly so by several male spectators who had actively wanted to avoid contact with this young, naked, and vulnerable woman. There is, of course, no reason why the spectator could not either refuse to participate or choose to leave, and both choices would be respected and responded to by the actors as legitimate options. Yet the majority of spectators did participate, and, indeed, it is from scenes such as this that the show derives much of its power, by creating the sense of danger and boundary crossing, not to mention by giving spectators access to an experience and a space otherwise locked away in the past.

The ethical issue is not simply about power, and discomfort with that power, but is about how memory functions. In Laundry, it is as if the past is not simply being re-enacted but is actually reanimated into a present-past, and this is in large part due to its site-specific setting. The reality “value” of the building itself, from the ante-room for visitors to the still-grand internal chapel, lends the imagined and constructed performance a greater weight and sense of authenticity. If the experience of being incarcerated in the laundry was, for the majority of the Magdalene women, a traumatic experience, then the reanimation of the past is also, by extension, a reanimation of that trauma. Audience members, who are more like participants than distanced spectators, may thus find the experience of the show not simply unsettling but actually traumatic (the lack of boundaries is also, of course, an issue for the actors). The ethical question with regard to Laundry thus centers on the risk that a commemorative and ethical-memory-oriented theater piece, which is site-specific and actively asks for audience participation, may not enable sufficient critical distance between the spectator and spectacle to prevent the show from becoming a transference of trauma. This potential risk returns us to the question of whether theater wants to tell a familiarizing or de-familiarizing narrative: can a narrative that is too de-familiarizing ultimately render it unproductive?

While, as an audience member, I experienced Laundry as a powerful, emotive, and thought-provoking production, I am aware that other spectators found the experience alienating, as they found themselves positioned in scenarios where they felt disempowered and vulnerable. Though this experience may, in itself, mimic the experience of the thousands of women who entered Ireland’s Magdalene laundries, it remains for us to ask whether the re-animation of trauma, or the production of guilt in a modern audience for the crimes of the past, are appropriate commemorative processes.

Indeed, if we read Hayley in The Walworth Farce as an unwitting audience member, we can see the potential emotional trajectory of moving from spectator to participant. Hayley enters as an initially confident, friendly, and outgoing young woman. She then goes through a series of emotional states, from being “confused” to “laughing,” to “annoyed,” “irritated,” and exasperated, to “crying,” until she finally escapes.[13] This emotional trajectory from an interested and engaged spectator to a traumatized witness illustrates how the performance of memory can be “a present and ethically complicit act for performers and spectators alike.”[14] Hayley’s complicity in the performance, in fact, leads directly to Blake’s death. This is not to say that audience members of all theater-as-memory productions are necessarily traumatized; rather, it is to call attention to the mutual and potentially overwhelming relationship between spectacle and spectator, in which both sides—the performance and the audience member—is affected and disrupted by the presence and actions of the other.

In her review of The Walworth Farce, Kim Solga argues that Walsh’s play raises questions about what role theater can play “as a site of witness” in the exploration and resolution of pain.[15] Solga states that “the theatre, more often than we care to admit, may do very little good, or even do real harm” and that the closure of this play “offers absolutely no comfort.”[16] Rather than producing catharsis and change, the ending of the play shows Sean begin a new and equally destructive farce. While I would not want to draw too strong a conclusion from this about theater as a whole, I think Solga is right to identify that—to paraphrase Walsh—if we are the stories we tell ourselves, then we need to be very careful about how we shape and perform those stories.[17]

Despite these questions, or perhaps because of them, productions such as The Blue Boy and Laundry are vital not only for their contribution to a living theater culture within Ireland, but also to the debate about the Irish past. What is valuable about these performances is the multiple ways they both open up a history of abuse and encourage active participation from spectators. What is dangerous about any theatrical production as a resource for dealing with a history of suffering is not its experimentation but, as Dinny says, the potential to get “stuck in a pattern.”[18]

The theatrical experiments of Walsh, Brokentalkers, and ANU Productions encourage us as theater scholars to think about theater-as-memory as a way of interacting with and presenting the past. And, ultimately, the success of each of these performances of the past is entirely dependent on the audience’s act of recognition, without which the memories cannot attain meaning. This recognition is part of what Paul Ricoeur calls, quoting Freud, “the work of remembering.”[19] This particular conception of remembering is that of memory as a force to be exercised, a labor to be undertaken. All three of these theatrical productions clearly aim to provoke an audience into developing an active reaction, whether that is positive or negative, and by doing so to make the audience reflect not only on the production—the “inside” world—but also on what lies beyond the theatrical space—the “outside” world. As Ricoeur posits, “the major question regarding the transmission of the past: Must one speak of it? How should one speak of it? The question is addressed to the citizen as much as to the historian.”[20] It is for this reason, then, that the major achievement of theater-as-memory is to remind an audience of their roles as citizens.

[1] One telling moment, for example, occurs when Dinny adds in this “new line”: “The truth is I haven’t worked for six years, Dinny.” The improvisation is part of Dinny’s response to Sean’s “cutting corners” on the story and leaving out lines. Though the story is all invention, Dinny accords it the status of fact: “The story doesn’t work if we don’t have the facts.” See Enda Walsh, The Walworth Farce (London: Nick Hern Books, 2007), 13.

[2] Ibid., 38.

[3] Ibid., 58.

[4] Patrick Lonergan comments, for instance, that Walsh introduces “realism” through the character of Hayley, which is achieved because she is “a normal person”; see Lonergan, review of The Walworth Farce, Town Hall, Galway, Irish Times, March 22, 2006, 14. Charlotte McIvor argues that the realism Hayley introduces is racially inflected: Hayley’s “appearance disrupts the obsessive repetition of distorted (Irish) family history […which] ultimately results in a series of real deaths. […] Hayley’s role as outsider is intensified by her racial difference”; see McIvor, “The Walworth Farce: Review,” Theatre Journal 62, no. 3 (October 2010), 463.

[5] Walsh, Walworth Farce, 60.

[6] Ibid., 58.

[7] Ibid., 32, 23.

[8] Loughlin Deegan, The Ulster Bank Dublin Theatre Festival Programme 2011, n.p. The program can be found at “Ulster Bank Dublin Theatre Festival Programme 2011, accessed May 26, 2014, http://issuu.com/shaunalyons/docs/ubdtf2011_issu_download.

[9] Brokentalkers, The Blue Boy (unpublished script), 4. Made available to the author by Brokentalkers.

[10] Or so he did during the performances attended by this author.

[11] Brokentalkers, The Blue Boy, 22.

[12] Here I am paraphrasing Paul Ricoeur’s definition of memory in Memory, History, Forgetting: “a being was presented once; it went away; it came back. Appearing, disappearing, reappearing.” See Ricoeur, Memory, History, Forgetting, trans. Kathleen Blamey and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 429.

[13] See Walsh, Walworth Farce, 46, 48, 50-1, 75, 83, respectively.

[14] Phil Hansen and Bruce Barton, “Memory,” Canadian Theatre Review 145 (Winter 2011), 5.

[15] Kim Solga, “Realism/Terrorism: The Walworth Farce,” Canadian Theatre Review 145 (Winter 2011) 91.

[16] Ibid.

[17] I paraphrase Dinny here; see Walsh, The Walworth Farce, 44.

[18] Ibid.

[19] As he states in reference to Freud, “it is on the level of collective memory, even more perhaps than on that of individual memory, that the overlapping of the work of mourning and the work of recollection acquires its full meaning”; see Ricoeur, Memory, History, Forgetting, 79

[20] Ibid., 452.