This article sets out to explore the tradition of translation and performance of Irish drama in Galicia, a north-western region of Spain largely unknown to international audiences because of the way in which its language and culture have been rendered invisible by its geopolitical position and history. Focusing on the recent incorporation of one particular play, Martin McDonagh's A Skull in Connemara, I will explore some of the key factors governing re-actualizations of Irish theater on the Galician stage, attending to constructions of Irish identity and their particular importance in processes of Galician self-recognition, and to the central function of translation within contemporary Galician culture. As I will show, the function of translation in this case should be seen both in its role as a way to strengthen a minoritized literary system and to fill a perceived gap in the theater repertoire.[1]

My analysis will combine key insights from descriptive translation studies regarding the relationship between source and target languages and cultures, with close attention to the specifics of both Galician and Irish literature and theater. At the same time, I attend to the creativity of agents who mediate between these systems—agents like translators or theater directors—in order to show the complexity of their negotiation between the domestic and the foreign. Ultimately, I will demonstrate the balance between what Lawrence Venuti calls “domestication” and “foreignization” in the performance-oriented translation process of adapting Martin McDonagh for the contemporary Galician stage.[2]

Arguably, few national identities are as internationally recognizable as the Irish, due to an array of cultural references that populate the collective imaginary both within and beyond its geographical borders. Long before the Celtic Tiger catapulted the country to the international foreground in ways that transcended the purely economic, Ireland could count cultural products as some of its most visible exports—among them, numerous Irish playwrights and dramatic works. In Spain, from the early twentieth century onwards, we find a considerable number of plays by Irish authors being translated not only into Spanish but also into other languages in the Iberian Peninsula—Catalan, Basque, and Galician. Given the minoritized status of these cultures within the broader Spanish context, translation must be considered a priori as a step towards supplementing their literary systems. In the case of the Galician system, the incorporation of Irish drama has been marked not only by minoritization but also by idiosyncratic perceptions of Ireland, rooted in the popularized belief that Ireland and Galicia share common origins.

This belief in common origins begins in the nineteenth century: Eduardo Pondal and other authors associated with the revival and rehabilitation of the Galician language and cultural identity—what was known as the Rexurdimiento—drew a poetic connection between Ireland and Galicia on the basis of them sharing a common Celtic past. This mythical common origin went on to be used by the emerging Galician nationalist movement during the early twentieth century in an attempt to legitimize claims for cultural recognition and increased autonomy from the Spanish central government in Madrid by drawing a parallel with the Irish political situation. Ireland thus became a paradigm for the consolidation of a distinct cultural and political identity. It was at this very time that the incorporation of canonical texts from Irish dramatic literature was initiated, with the publication of W.B. Yeats’ Cathleen Ní Houlihan in one of the key organs of Galician nationalist discourse, the Revista Nós, in 1921.[3] This translation ultimately exemplifies the extent of Galicia’s mystified identification with Irish culture, an identification that, as I will show, has continued to affect the incorporation of cultural products from Ireland up to the present day.

At present, translation is considered in the Galician context as a very valid source of creative material for theater practitioners, but this was not always the case. The early twentieth-century cultural revival triggered public debate over the issue of translation as a legitimate strategy to redress the lack of original texts in Galician language. The discussion resumed in the 1960s during the later years of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, within the frame of another reconstruction process: the resurgence of the Galician language in the public space after its repression in the post-Civil War years. Whereas many advocates of translation thought it quite legitimate to augment the Galician corpus by means of translated plays, others regarded translation as inadequate to the task of establishing a national theatrical canon; for the latter, only texts originally written in the Galician language should be included in the repertoire. Nevertheless, the debate was progressively sidelined throughout the 1970s, during which time the relative number of productions of translated plays increased rapidly, including a significant number of plays from the Irish context.[4] As observed by Noemí Pazó, an affinity between Galicia and Ireland is explicitly mentioned in theatrical paratexts—programs, for example, as well as other promotional materials—that frame works by Sean O’Casey and J.M. Synge.[5] The foundation in 1984 of the Centro Dramático Galego (CDG), the Galician national theater ensemble, has since strengthened the position occupied by translation in the Galician theatrical system. From its early days, the CDG has alternated productions of Galician originals with translations of both classic and contemporary texts, contributing to the consolidation of a canon of translated dramatic literature in the Galician language.

The most recent author to enter the canon of Irish drama translated into the Galician language is Martin McDonagh. At this point in time, three works by the playwright—namely, the three plays comprised in the “Leenane Trilogy,” as it is referred to—have been staged in Galicia by two different professional companies. The first of them, The Beauty Queen of Leenane, translated by Avelino González and Olga F. Nogueira, was performed bearing the title A raíña da beleza de Leenane by Teatro do Atlántico under the direction of Xúlio Lago in 2006, ten years after the original Irish production was staged by Druid Theatre in Galway and London.[6] Producións Excéntricas undertook adaptations of the other two plays in the trilogy, in quick succession, under the direction of Quico Cadaval: Un Cranio furado (A Skull in Connemara) in 2010 and Oeste solitario (The Lonesome West) in 2011. In both of these instances, too, the company worked with Avelino González, whose role as initiator of the translation of McDonagh and own particular modus operandi will be discussed below in greater detail. It is worth noting that Martin McDonagh’s plays are present in the Galician context only as performance texts, as the Galician language translations remain unpublished. As we shall see, this is in large part due to the nature of the translation process involved, which was a collaboration that focused heavily on performance and performability.

All three productions of Martin McDonagh’s works in Galician won several María Casares awards, including one for “Best Translation/Adaptation.”[7] A more telling indicator, however, of the plays’ impact—in so far as it denotes exposure beyond the geographical borders of Galician-speaking territory—may be the nomination of Oeste solitario to the Premios Max awards that acknowledge the work of professionals from the whole of the Spanish state. As a minoritized language, Galician does not enjoy the same status as Spanish in terms of general cultural influence, despite apparently favorable legal and institutional structures.[8] An awards nomination beyond the community brings recognition, and visibility; in commercial terms, it is likely to have a positive impact on the prestige of the play among Galician audiences, above all among those who are not habitual Galician speakers.

The collaboration between Avelino González and Producións Excéntricas has resulted in several successful productions, albeit ones that entail a markedly target-oriented reading of Martin McDonagh’s original. This is particularly true in the adaptation of A Skull in Connemara, Un cranio furado. Judging from media responses to the play, both audiences and critics have broadly accepted the Galician company’s realistic interpretation of McDonagh’s original. In fact, in contrast to the play’s original text and production, the Galician version has been seen as a truthful picture of rural life, more so, certainly, than would ever possibly be accepted by Irish audiences. This re-interpretation is built upon identification with the Irish context and reinforced through linguistic choices and other performative devices. Whereas the Irish may see in McDonagh a caricatured representation of Ireland through a compendium of stereotypical features, non-Irish audiences are more likely to simply recognize what they believe to be “real” Ireland. And Un cranio furado takes Galician audiences a step further: they are encouraged to recognize themselves. The distillation of Irish identity present in Un cranio furado will thus be read here as an attempt not so much to open the eyes of the Galician public to a different culture but to mirror how Galicians perceive their own ethnicity, their own national identity. The play works not because it is about the other but because it is about the “us,” the “nós.”

To support this claim, it is necessary to further consider the recent incorporation of Martin McDonagh’s “Leenane Trilogy” as a legitimizing strategy both in the wider context of Galician translation history and practice and, above all, in terms of the added prestige associated with the paradigmatic role of Ireland in the construction of contemporary Galician national identity. In this context, McDonagh’s association with Irish culture, as well as his international renown, deeply informs the choice of his plays for translation into Galician. By the time McDonagh’s works arrived in the Galician cultural context, ten years had lapsed since The Beauty Queen of Leenane premiered in Galway. In that time, he had gained recognition not only through his dramatic works but also as a screenwriter, with award-winning films like Six Shooter (2005) and In Bruges (2008). Yet, despite their widespread international exposure, his plays have generated a considerable amount of controversy around not only the author’s problematic treatment of Irish ethnicity but also his very own ethnicity. I wish to briefly turn to several examples of these well-known debates over McDonagh's Irishness in order to shed light on the shifts that take place in the translation of his work into a Galician context.

Often referred to as “London-born Irish,” McDonagh has always avoided labelling himself as either Irish or British. Criticisms of his dramatic works usually reference his controversial depiction of Irish society, often equating it to an outsider’s mocking portrayal of the rural West of Ireland. Elizabeth O’Neill succinctly describes in her review of The Lieutenant of Inishmore the prevailing attitudes towards the double nature of McDonagh and his works:

A modern day Synge or an English chancer? [...] Audiences have been divided roughly into two camps; those who think he’s captured the black humour and zeitgeist of a postmodern rural Ireland, and those who see him as making a mockery of Ireland and the Irish by lampooning that caricature of old, the “stage-Irish” fool.[9]

Similarly, in a profile on McDonagh published by The Guardian, Henry McDonald quotes author Malachi O’Doherty’s views: “To me a lot of Martin McDonagh reads like paddywhackery. […] The Irishness of the people is part of the joke. You can see in a writer like Beckett, who was Irish, that when he depicts the depleted human condition, he does it without reference to ethnicity.”[10] At a time when cultural products cross borders more easily than ever—due to the increased accessibility of those products brought about by the numerous modes of transmission and media now at our disposal—distinctions like those detected by O’Neill and made by O’Doherty nevertheless indicate a cultural setting in which the issue of national identity is a recurrent topic of discussion.

Indeed, in the Irish cultural context, attempts to define the essential features of Irishness are commonplace. For example, in an article published in The Irish Times in 2012, Patrick Freyne lists the ideologies that he believes “have shaped Irish identity over the past century,” including a number of “isms” (among others, he lists, Celticism, Catholicism, alcoholism, and localism), as well as several references to Celtic Tiger-related concepts (such as “brand” Ireland and cosmopolitanism).[11] Freyne’s piece is not a kind of overview of Ireland intended for non-Irish readers but an account of Ireland designed to encourage reflection and discussion among the Irish regarding those factors that have affected the makeup of their society in recent times. Freyne’s article exemplifies the more general Irish concern with self-definition.

Undeniably, McDonagh’s national identity would be deemed incidental, as is the case with many other authors, were it not for the themes he explores in his plays and the attributes he bestows upon his characters. The inhabitants of the fictionalized Leenane that he creates are loaded with markers of Irishness, albeit rather conventional ones. Very possibly, Martin McDonagh’s use of ethnic and cultural clichés is offensive not so much in itself but because he is “not Irish enough,” a claim sustained by novelist and journalist Adrian McKinty on his blog:

Of course no one likes stereotypes but I think McDonagh is being picked on because of his “Englishness”—always the bogey man for a certain class of critic. The gate keepers of Irishness are on very shaky ground when they try to exclude people with planter names (Gerry Adams) or Norman names (the entire Fitzgerald clan) or anyone who's spent the majority of their life living outside the 32 counties (Yeats, Wilde, Joyce, Beckett, Swift, etc.) [...] So let’s keep London born McDonagh and just to balance things out I'll gladly swap all four of those proud non tax paying Micks in U2 for him.[12]

McKinty’s polemical register suggests just how fraught these issues of Irishness and Irish national identity are in the critical response to McDonagh’s work.

This controversial side of Martin McDonagh’s reception remains fundamentally overlooked or even ignored in Galicia.[13] This does not mean, however, that his national or ethnic identity is obviated. On the contrary, his name is regularly followed by descriptive references that position his work in the context of both the Irish and British cultural systems and reflect the author’s dual background. For example, on the website of Producións Excéntricas, the company describes their production of Un cranio furado as follows:

Unha obra moderna, comercial, divertida, escrita por un explosivo e novo autor anglo-irlandés nos 90, martin [sic] McDonagh, que tiña tanta vontade de provocar ó tradicional mundo irlandés que herdaba como horrorizar ó requintado público urbano londinense. (A modern, commercial, fun work, written by an explosive young Anglo-Irish author in the ‘90s, Martin McDonagh, who had as much desire to provoke the traditional Irish world that he was inheriting as to appal the refined urban London audiences.)[14]

In the Galician context, McDonagh is sometimes referred to—as he is above—as “anglo-irlandés” (Anglo-Irish), a label that may succeed in communicating the duality of the author’s national identity to local Galician audiences yet is loaded with socio-political meanings in the Irish context. Although the problematic delimitation of the term is well-documented,[15] the majority of Galician spectators are likely to remain unaware of its colonial overtones and to accept the simplified image of Irish identity that is laid before them.

Mentions of Martin McDonagh in promotional materials and press releases point repeatedly to his Irish origin as well, and on occasion they do so to the point of attributing him iconic status, as we see in the following excerpt from the Teatro do Atlántico website for their production of A raíña da beleza de Leenane:

Considérase que McDonagh é unha nova voz e tamén unha nova calidade no drama irlandés suxeríndose que está a facer por aquela dramaturxia o que Pogues fixo pola música irlandesa tradicional nos anos 80. (McDonagh is considered a new voice and also a new quality in Irish drama, suggesting that he is doing for that dramaturgy what The Pogues did for traditional Irish music in the 80s.)[16]

The identification of McDonagh (and The Pogues) as belonging to the Irish cultural milieu is determined by target system perceptions; in other words, it is rooted in the condensed image of Irish culture that has come to exist in the Galician context—what is, in recent times, the existence of an identifiable international cultural image generated from the Irish source system (the “brand” Ireland of Freyne’s overview). In his influential work Theatre and Globalization: Irish Drama in the Celtic Tiger Era, Patrick Lonergan discusses in detail how the reception of Irish theater has been affected by globalization and proposes a definition of Irish drama that reflects the current “shift from geographical to conceptual spaces”: Irish plays are not necessarily plays produced in either of the two Irish states but “plays that are marketed or received internationally as corresponding to the Irish ‘brand.’”[17] In defining the Irish dramatic canon, as Lonergan proposes, according to the “conceptual” as opposed to the geographical—according to whether a play carries the Irish “brand”—Martin McDonagh’s place within that canon is assured. However, the notion of the “brand” also draws attention to the contrast between what is perceived as Irish in the Irish context and what international audiences identify as “Irish”; this contrast is ultimately exemplified by the reception of McDonagh’s works in their Galician adaptations.

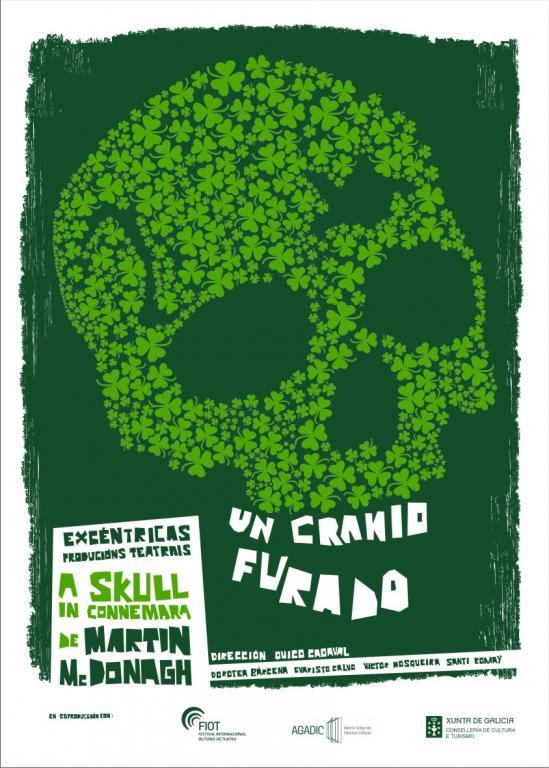

Indeed, the way in which McDonagh’s plays have been marketed in Galicia points unequivocally to an Irish “brand,” with Irish motifs featuring prominently in the case of Un cranio furado—again, Producións Excéntricas’ take on A Skull in Connemara. The main image chosen to represent the play on promotional cards and posters is a skull made up of shamrocks in two contrasting shades of green.[18] In addition, the original title and the author’s name feature very prominently on the promotional materials, highlighting the fact that we are faced with a translation and encouraging audiences to assume the “Irishness” of the play. If anything, this distillation of Irish identity is heightened by the removal of any reference to Connemara in the Galician title of the play, which literally translates “a perforated skull,” leaving the audience with a more generic vision of the “conceptual” space of Ireland, no longer attached to geographical spaces. Yet, as we shall see below, this shift will also allow easier identification of the space evoked in the play with rural Galicia. With their following production, Oeste solitario (Lonesome West), Producións Excéntricas omitted the original title, albeit including a more subdued allusion to it, in the form of its initials “LW.”[19] The image selected for the poster is a playing card depicting a “King of Shamrocks,” again resorting to the most formulaic symbol of Ireland, both easily and internationally recognizable. In both cases, the marketing choices put unambiguous stress on clichéd Irish imagery.

A rather conspicuous use of the Irish brand is present in several production choices, such as the use of Irish traditional music to introduce the play and the presence on stage of a selection of photographic images: stills of rugby games, St Patrick, and John Wayne characterized as Sean Thornton in The Quiet Man. This triad of references is unequivocally evocative of an Irish setting in the eyes of a Galician audience. Characters’ names, geographical references, and allusions to popular culture are preserved in the Galician text. In contrast, other foreignizing elements such as Irish-language terms are avoided; so, for example, the Irish “poteen” is replaced with the Galician “caña,” also a traditional home-made spirit.

A similar approach is taken with regards to characterization. The character of Mairtin Hanlon wears a Manchester United jersey with a “Keane” inscription on the back, as indicated in McDonagh’s stage directions, even though this name would mean very little in the minds of most Galician theatregoers. Precisely because of its transparency, this cultural hint fits in with the underlying translational agenda of the performance text—a nuanced domestication consisting not so much in erasing references to the source context but in molding them to respond to target context expectations, sidestepping naturalistic elements that might potentially distance the audience. Indeed, whereas both Avelino González and Quico Cadaval categorize McDonagh’s work as realism, they consciously avoided strictly naturalistic codes of representation, which would have entailed a meticulous depiction of an Irish household, in their opinion detrimental to creating a connection with the audience:

Que funcione é suficiente. O problema do teatro é un problema de convención: canto antes consigas que o espectador acepte, antes empezamos. […] Canto máis naturalista sexa o escenario, máis vai mirar a xente o que lle falta. Hai que acadar ese equilibrio entre naturalista e simbólico; no teatro ten que haber certa estilización. (If it works, that’s enough. The problem in theater is a problem of convention: the sooner you get the audience to accept, the sooner we get started. [...] The more naturalist a set is the more people are going to see what is missing. One must find that balance between naturalist and symbolic; in theater there must be some stylization.)[20]

When questioned about the importance of the plays’ “Irishness” in the decision to produce Martin McDonagh, both Avelino González and Quico Cadaval responded initially by downplaying this specific factor. However, as they developed their various arguments, it became increasingly clear that it was not an aspect that they could overlook. Indeed, Avelino González admited to being attracted to Martin McDonagh’s works because they were classified as Irish drama in the bookshop where he first found them and, as he declared, “Regromou en min o mito de Galicia e Irlanda” (“the myth of Ireland and Galicia reappeared in me again”). In his own words, when he read McDonagh, his reaction was to think “Somos nós” (“it is us [Galicians]”). When Producións Excéntricas decided to stage the play, it was, according to Cadaval, for essentially pragmatic reasons—the company’s permanent members were two male actors and A Skull in Connemara required them to cast just two more performers. Nevertheless, they reverted to that powerful Galicia-Ireland connection: “Inflúe na librería pero non á hora de escoller as obras. É algo que se aproveita despois, porque ese imaxinario que eu tiña, o ten tamén o público” (“It’s influential in the bookshop but not when it comes to choosing the plays. It is something you make the most of at a later stage because that imaginary that I had, the audience also has it”).[21]

In the course of the same interview, the translator Avelino González referred explicitly to his perception of a gap in the Galician dramaturgical canon when explaining his interest in the works of Irish playwrights, an interest which was sparked during a visit to the bookshop in London: “O encanto que tiñan estes paisanos é que escribían o que os dramaturgos galegos deberían escribir e non escriben” (“The appeal of those fellows was that they were writing what Galician playwrights should be writing but don’t”).[22] And director Cadaval further explained what McDonagh’s works could bring to the Galician stage:

Un territorio onde encontrar realismo pouco mixiricas, sen sentimentalismos, mesturado con elementos grotescos, non querendo atribuírlle a Irlanda unha serie de características poéticas e con referencias á modernidade. (A territory where one can find realism that is hardly whining, without sentimentalisms, mixed in with grotesque elements, without a wish to attribute a series of poetic characteristics to Ireland and with references to modernity.)

Comments such as these suggest that the plays’ controversial grotesque representations of dysfunctional characters and social interactions in the Irish rural milieu may hold the key for their successful incorporation to the Galician system, where McDonagh’s sui generis realism is regarded as full of valuable virtues. Cadaval interprets McDonagh’s code as a raw realism that makes no attempt to poeticize Ireland, at least not in the allegorical ways pursued by W.B. Yeats and his contemporaries. Arguably, the degree of stylization in McDonagh’s stage geographies could be seen as a poeticization of Ireland through the use of clichés of rural life, a vision that is reactualized by the “references to modernity” that Cadaval identifies in McDonagh’s work.

Moreover, Cadaval and González placed substantial emphasis on the fact that Galician authors were unable to provide original texts to match the performative and theatrical opportunities offered by McDonagh’s work. This became particularly clear when Cadaval referred to the plays as “what Galician playwrights should be writing and don’t write.”[23] González added further that McDonagh’s cultural background gave him “a boldness that we Galicians do not dare to have.”

Almost invariably, the gap in the Galician dramaturgical tradition observed by Cadaval and González is discernable in the paratextual materials that accompany productions of McDonagh. Usually the gap is articulated in slightly different terms but is always coupled alongside a mention of the correspondence between the Galician and the Irish setting. In the descriptive material for Producións Excéntricas production of McDonagh’s Skull, we again find a particularly revealing choice of words:

Os feitos acontecen en Connemara, mais podían pasar en Bergantiños se tivesemos alguén que os soubese escribir. Como non tiñamos, tivo Avelino González que domear en galego aquel bravo inglés que escribiu McDonagh. (“The events occur in Connemara, but they could come to pass in Bergantiños if we had somebody that knew how to write them. Since we didn’t, Avelino González had to tame into Galician the wild English that McDonagh wrote in”.)[24]

According to this view, González did not just translate, he “tamed” (“domou”) Martin McDonagh’s wild language. The attribution of an audacious, bold quality to the play harks back to the trope of the “wild Irish,” consistent with stereotyped perceptions of Irish identity. The passage furthermore implies that the source text contains an irreverence that the target Galician culture lacks and desires, a trait that can only be taken by force. The way in which this appropriation is presented echoes Lawrence Venuti’s words on the violence of the translation process; that is, in the case of translating McDonagh—and to quote Venuti—the “forcible replacement of linguistic and cultural difference” is framed as a feat on the part of the translator and coexists here with the recurring attribution of prestige to a source culture, with which an affinity is sought.[25]

The role of Avelino González as initiator has definitely marked the incorporation of the texts into the Galician system, not least because of his idiosyncratic approach to the translation process. His translations exhibit a clear emphasis on performability, speakability, and the overall dramaturgical viability of the texts he produces. He has stated that the work of the translator is “at the service of a concept of mise en scène.”[26] His ideas echo those of Hans J. Vermeer’s “skopos theory,” as the function of the translation—in this case, for performance—provides the rationale behind the linguistic choices, such that lexical decisions are often made on the basis of feedback from performers obtained during the rehearsal process. González’s working method favors this creative dialogue—when he comes across a play that he sees potential in, he prepares a draft translation, which he circulates amongst prospective companies. If there is interest, he then proceeds to work on a performance text that is by no means a definitive version but is rather a malleable, rough outline according to which the director and the performers can work. There is no doubt that his own personal experience as an actor informs his methodology, as does the fact that he is not a translator by trade. In his own words: “Eu non son traductor, atópome traducindo” (“I am not a translator, I find myself translating”). When he reads a play, he does so from the perspective of a performer, with both the advantages and limitations that perspective brings. While he has the advantage of an awareness of what works on stage and benefits from the opportunity to closely collaborate with the performers, González relies to a great extent on an intuitive identification of phraseology and context-specific elements.

The recurring references to a lacuna in the Galician theatrical canon raise the question of whether theater practitioners and audiences would show the same degree of recognition, or even tolerance, towards portrayals of rural Galician life that had originated in Galicia as they afford to McDonagh’s work, or would they begin to generate similar criticisms to those triggered by Martin McDonagh’s work in the Irish context. In Galicia, the ruralist theatrical tradition of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been condemned for its stereotypical and often offensive depiction of rural life, and its exploitation of clichés for comedic effect.[27] The cultural embrace of McDonagh’s work in the Galician context depends on a spectatorship that does not see such clichés but instead sees “realistic” depictions that encourage identification on the part of the audience and utilize the prestige associated with the Irish cultural context.

While the use of Irish symbols in the adaptation of A Skull in Connemara can be linked to the aforementioned mythical connection with the Irish nation in the Galician milieu, these stereotypes are also commonplace at a global level as markers of the Irish brand. Although different in many ways from the early twentieth-century identification utilized by the incipient nationalist movement in Galicia, there is a common strategic aim in the use of visual elements, as well as in the manner in which the play is framed, both in productions and publicity for those productions. Several production choices suggest that the success of the play relies on convincing the audience of the cultural proximity of Ireland to Galicia, such as is expressed in the following terms on the programs originally distributed at the performances of Un cranio furado: “Os feitos acontecen nun país de chan ácedo e alta pluviosidade. Pode ser Connemara como pode ser Bergantiños” (“The events take place in a country with acidic soil and high pluviosity. It can be Connemara or it can be Bergantiños”).[28]

It is clear, then, that the divided critical response surrounding Martin McDonagh’s work in the Irish context would cast a shadow over that aspect of his work that is so important for its overwhelming embrace in the Galician system—its Irishness. Debates in Ireland over whether the playwright deserves a place in the Irish canon do not attract any attention in Galicia; neither do the controversies around his use of ethnicity that, for many of his detractors, tread a fine line between the grotesque and the downright racist. There is no trace of these issues in the production of or reception to the plays in Galician, the overriding aesthetic of which is far more “realistic” than their Irish original. However, as I have shown, these aesthetic and commercial choices that inform McDonagh’s “translation” for the Galician stage aim to fill a particular gap in the Galician system; specifically, what McDonagh provides is a theatrical language capable of representing contemporary rural Galicia without the baggage of its own contentious ruralist tradition.

More than the usual understanding of domestication in the context of theater translation—what we have gathered from Venuti’s important work—the Galician taming of McDonagh entails both strategic appropriation and identification with the foreign—in this case, the Irish—and the expansion of its own domestic forms of representation. The particular case complicates any simple juxtaposition of domestication and foreignization and calls for more context-sensitive histories of processes of cultural translation.

The author would like to specifically acknowledge the Irish Research Council, without whose continued support this article would not have been written.

[1] The term “minoritized” is preferred to other formulations because it refers to languages whose lack of symmetry in relation to a dominant language has been caused by some level of colonialist intervention, a nuance of meaning that is not contained in terms such as “minority” or “lesser-used,” terms that could refer simply to the number of speakers of a language. For a discussion of the contrast offered by these terms, see Aguilar-Amat and Laura Santamaría, “Terminology policies, diversity, and minoritized languages,” in Translation in Context: Selected papers from the EST Congress, Granada 1998, ed. Andrew Chesterman, Natividad Gallardo San Salvador, and Yves Gambier (Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2000), 74-75.

[2] Venuti refers to “domestication” when a translation is inscribed with target system values and simultaneously conceals the translation process by presenting the text as a faithful reflection of the original. Conversely, “foreignizing” translation attempts to convey the cultural difference and linguistic otherness contained in the source text. See Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (London: Routledge, 1995).

[3] Signed by Antón Villar Ponte, the text was accompanied by poems and pseudo-anthropological articles on Ireland, as well as several references to Terence McSwiney, the late Lord Mayor of Cork, who had recently died on hunger strike. Numerous instances of intertextuality suggest that Villar Ponte’s main source text was Marià Manent’s Catalan version of the Yeats’ play, which appeared in La Revista earlier that year. The silencing of this mediation process is consistent with the explicit agenda of the Revista Nós, namely the suppression of intermediaries in establishing links between Galicia and other cultural contexts. This information was originally gathered for Elisa Serra Porteiro, “Ten ar de forasteira: Villar Ponte’s Galician translation of W.B. Yeats’ Cathleen Ni Houlihan,” (paper presented at The Speckled Ground: Hybridity in Irish and Galician Cultural Production conference, Galway, March 30, 2012). For an analysis of the incorporation of Yeats to the Galician system see Silvia Vázquez Fernández, Translation, Minority and National Identity: The Translation/Appropriation of W.B. Yeats in Galicia (1920-1935) (PhD diss., University of Exeter, 2013).

[4] In 1960, the Escola de Teatro Lucense staged J.M.Synge’s O casamento do latoneiro (The Tinker’s Wedding) and the Santiago de Compostela-based Ditea produced Cabalgada cara o mar (Riders in the Sea) in 1972. The same company inaugurated in 1976 their “Ciclo irlandés,” or “Irish cycle,” a series of productions of texts by Irish playwrights, including Sean O’Casey and W.B. Yeats.

[5] Noemí Pazó, “Teatro e tradución. Unha prospectiva xeral,” in Cento vinte e cinco anos de teatro en galego. No aniversario da estrea de A fonte do xuramento 1882-2007, ed. Manuel F. Vieites (Vigo: Editorial Galaxia, 2007), 309-10.

[6] This was not the only translated Irish play produced by Teatro do Atlántico, having already staged Conor McPherson’s O encoro (The Weir) in 2004 and Brian Friel’s O xogo de Yalta (The Yalta Game) in 2009.

[7] As with most awards, their significance as a measure of quality or impact is relative, to say the least. The “María Casares” are presented on a yearly basis by the members of the Asociación de Actores e Actrices de Galicia (Galician Actors Association), and all Galician-language productions are automatically nominated. Furthermore, translations and adaptations will almost invariably be judged without knowledge of the original text.

[8] Despite the changes in legislation carried out during the 1980s, language-related prejudices and negative stereotypes continue to exist, raising questions not only about the efficacy of linguistic policies but also about the rationale behind them. See Xosé Ramón Freixeiro Mato, Lingua galega: normalidade e conflito (Santiago de Compostela: Láiovento, 1997), 137.

[9] Elizabeth O'Neill, “Theatre Review: The Lieutenant of Inishmore” RTÉ, October 1, 2003, http://www.rte.ie/ten/2003/1001/inishmore.html. [The editors wish to note that the link to this review is permanently broken, but that the author has received written consent from O’Neill and RTÉ to quote from this review. For a similar explication of the double-sided reception of McDonagh’s work, see Karen Vandevelde, “The Gothic Soap of Martin McDonagh,” in Theatre Stuff: Critical Essays on Contemporary Irish Theatre, ed. Eamonn Jordan (Dublin: Carysfort Press, 2000), 293.]

[10] Henry McDonald, “The Guardian profile: Martin McDonagh,” The Guardian, April 25, 2008, http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2008/apr/25/theatre.northernireland.

[11] Patrick Freyne, “Drink! Fecklessness! Partitionism! Shame! The Irish ideologies,” Irish Times Weekend Review, September 8, 2012, 4.

[12] Adrian McKinty, “Is Martin McDonagh Irish Enough?” The Psychopathology of Everyday Life—Adrian McKinty's Blog, February 10, 2009, http://adrianmckinty.blogspot.ie/2009/02/is-martin-mcdonagh-irish-enough.html.

[13]In the course of a personal interview with Xúlio Lago and María Barcala—director and actor, respectively, with Teatro do Atlántico—both were inititally surprised to find out about the strong public reactions to Martin McDonagh’s drama, which they tentatively attributed to that public’s “lack of contact with rural reality”; María Barcala and Xúlio Lago, interview with the author, Culleredo, April 17, 2013.

[14] “Un cranio furado (A Skull in Connemara),” Producións Excéntricas, accessed May 28, 2014, http://www.excentricas.net/gl/espect%C3%A1culos/List/show/un-cranio-furado-a-skull-in-connemara-235.

[15] See Anne MacCarthy, Identities in Irish Literature (Weston, FL: Netbiblo, 2004).

[16] “A raíña da beleza de Leenane (The Beauty Queen of Leenane),” Teatro do Atlántico, accessed May 28 2014, http://www.teatrodoatlantico.com/index.php/gl/espectaculos-anteriores/49-leenane. (last accessed: 31 January 2013).

[17] Patrick Lonergan, Theatre and Globalisation: Irish Drama in the Celtic Tiger Era (Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009), 28.

[18] An image of the poster can be viewed here: http://static.plenummedia.com/34076/images/20101020165136-skull-web.jpg?d=500x0, though it reproduced here at the top of this article.

[19] An image of the poster can be viewed here: http://static.plenummedia.com/34076/images/20110916115942-lonesone-west-web-web.jpg.

[20] Quico Cadaval and Avelino González, interview with the author, Santiago de Compostela, September 3, 2011.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] “Un cranio furado (A Skull in Connemara),” accessed May 28, 2014.

[25] Venuti, Translator's Invisibility, 18-19.

[26] Cadaval and González, interview.

[27] See Laura Tato Fontaíña, Historia do Teatro Galego: Das orixes a 1936 (Vigo: A Nosa Terra, 1999).

[28] Producións Excéntricas (program for Un cranio furado, Santiago, 2011).