Gallipoli. Produced by Century Ireland. gallipoli.rte.ie.

For much of the twentieth century, Ireland suffered from selective amnesia when it came to the Great War. Legends about the Ulster Division’s sacrifice at the Battle of the Somme stirred some quarters in Northern Ireland, but much of the island seemingly chose to forget the wider war-time context for the events of the Easter Rising. This began to change rapidly in Irish academia and culture in the early 1990s, and now, in this decade of centenaries, Ireland is pointedly choosing to remember the experiences of tens of thousands of Irishmen in khaki uniforms.

Gallipoli was the first major theater of war for many of these young men. Winston Churchill’s doomed notion was to attack Germany’s ally, Turkey. By capturing Constantinople, the Allies could simultaneously take Turkey out of the war while also freeing up much-needed supply channels to Russia. The naval campaign in March of 1915 was a fiasco; the decision was then made to attempt a land invasion on the Gallipoli peninsula on the northern bank of the Dardanelles. Allied forces met with fierce Turkish resistance. What Churchill had envisioned as a swift master-stroke quickly turned into yet another stretch of barbed wire and trench warfare. After eight weary months of fighting and half a million casualties between the two sides, including over 100,000 dead, the campaign was abandoned by the Allies. The Dublin, Munster, and Inniskilling Fusiliers all took part at Gallipoli, along with the 10th (Irish) Division, the first of Lord Kitchener’s volunteer Irish divisions to see battle. Unlike the 16th (Irish) or 36th (Ulster) Divisions, the 10th was not recruited along sectarian or political lines, so it perhaps best reflected the complexities of Irish participation in the imperial war effort. Although memories of Gallipoli tend to focus on the tragedies associated with the Australia New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) soldiers and their futile efforts to gain ground against the Turks, many nations were represented within Allied forces at the Dardanelles, including the French, South Africans, Indians, and Newfoundlanders. Some 12,000 Irishmen fought at Gallipoli, and 4,000 of them never returned home.

The RTÉ website Gallipoli Ireland is part of the ongoing Century Ireland history project in association with Boston College, designed to highlight “ongoing realtime” Irish experiences in the period between 1913 and 1923. Gallipoli’s choice for inclusion in this endeavor demonstrates not only the undeniable interest Ireland now has in the country’s participation in the war effort, but also serves to underscore how this “sideshow” campaign encapsulated many of our most familiar tropes from the Great War: slaughter, sacrifice, hubris, fraternalism, nascent nationalism, and the bravery of ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances. The site serves as both a primer for those unaware of the Dardanelles Campaign and as a source for more in-depth information and analysis. Its creation marks the 100th anniversary of Gallipoli while also highlighting the Irish content of the campaign, which previously has gone relatively unnoticed.

The site’s greatest strength is the accessibility of its content. Its layout is straightforward and easy to navigate, but the gems come in the form of a series of video clips, audio episodes, and day-by-day accounts from diaries of eye-witnesses to the attacks on Cape Helles and Suvla Bay. Professor Lucy Collins discusses the contentious enlistment of Irish poet Francis Ledwidge, while Professor Keith Jeffery notes Gallipoli’s importance to the overall strategy of the war as it existed in Churchill’s mind at the beginning of 1915. A most interesting inclusion among the video selections is an analysis of “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda” by former Pogues member Cáit O’Riordan, who notes how John Bogle’s folk song has touched audiences across geographic and generational lines. The audio selections include half a dozen excerpts from RTÉ’s The History Show on such topics as Irish-born members of the ANZACs and the centenary of the battle.

Two standout interactive areas on the site are its “Guides” and “People” sections. The guides are very user-friendly introductions to an interesting series of topics central to the Gallipoli campaign, including Irish leadership of the Zion Mule Corps, Victoria Cross winners from Ireland, food and leisure activities, and an exploration of how men died on the battlefield. The “People” section includes realtime diary excerpts from an Irish nurse and numerous Irish soldiers, such as Guy Nightingale from the Royal Munster Fusiliers and John McIlwain of the Connaught Rangers, along with selections from death notices. Juxtaposing the frank tones of the diary entries alongside the formal, stilted language of the death notices is a stark reminder of how impersonal histories of war can be without a concerted attempt to highlight the human factor in each story. The “Galleries” incorporate images, photographs, and artwork from the collections of the Imperial War Museum, the National Library of Ireland, the National Archives at Kew, and the National Museum of Ireland, as well as archives in France and Australia.

The final section of the website is dedicated to educational links. While this often can be a section that many overlook on a given website, this version has some of the most pertinent information for those curious to know more about Irish participation in this part of the war effort. Worksheets from the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland and the National Library of Ireland are geared to a range of ages and include more analyses of women’s roles in the war as well as recruitment and propaganda campaigns. The “Books and Websites” page demonstrates the growing interest in Gallipoli’s Irish dimensions. Recommended titles include Myles Dungan’s classic Irish Voices from the Great War (1995), Philip Orr’s Field of Bones (2006) and Jeff Kildea’s Anzacs and Ireland (2007), along with a number of primary materials from the war years and the 1920s. Among its listed websites, the most fascinating one might be the Irish Anzac Database, which was created with the impressive goal of documenting the thousands of Irish-born men who served in the war—including at Gallipoli—as ANZACs.

The Century Ireland Gallipoli website is a welcome addition to the numerous materials memorializing and analyzing experiences of war a century ago. Whatever one’s sentiments about Irishmen in British uniforms, successful projects like this one ensure that the evocative experiences of these individuals take their place alongside more familiar events from 1916 and after.

Credits:

Images 1-2 depict the 7th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers leaving the Royal Barracks in April 1915. From Dublin, the Battalion traveled to Basingstoke for training and then departed for Gallipoli. These images are provided by the National Museum of Ireland.

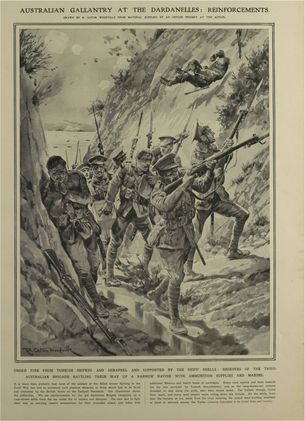

Image 3 depicts Australian soldiers under fire on June 5 1915. This image may be found in Illustrated London News.

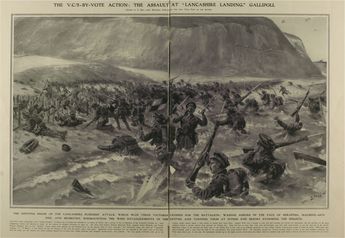

Image 4 portrays the Lancashire landing on September 4 1915. Illustrated London News.