Joan FitzPatrick Dean. All Dressed Up: Modern Irish Historical Pageantry. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2014, xvii + 335 pp.

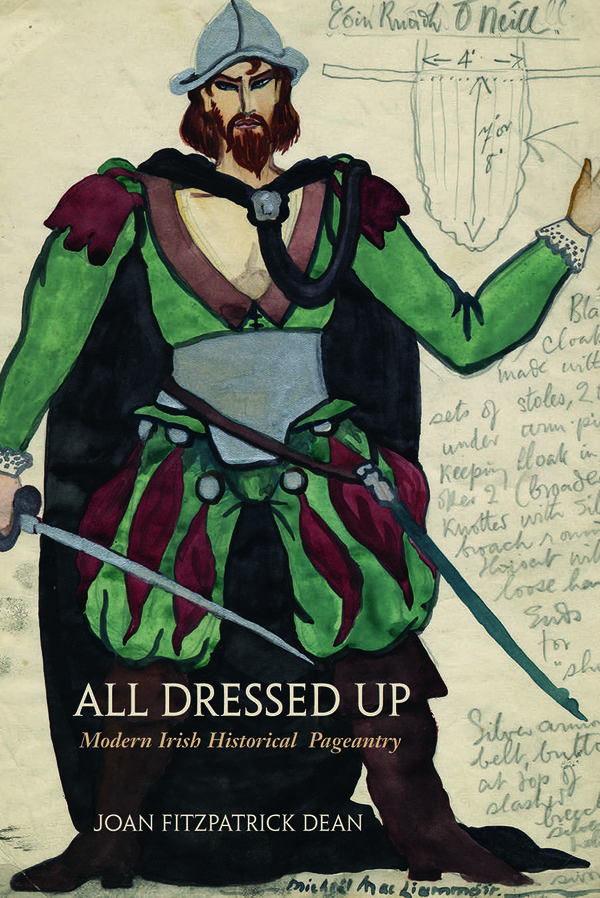

The history of public spectacle in an Irish context goes back at least to Daniel O'Connell's monster meetings of the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and includes republican funerals, commemorations, Gaelic League Processions, and tableaux vivants. Aspects of this tradition in the early twentieth century have been studied by, among others, Paige Reynolds, who considers the element of spectacle at the intersection of Revivalism and Modernism in Modernism, Drama, and the Audience for Irish Spectacle (Cambridge University Press, 2007), and Timothy McMahon, who addresses the parades and performances put on by the Gaelic League at the turn of the century in Grand Opportunity: The Gaelic Revival and Irish Society, 1893-1910 (Syracuse University Press, 2008). In her marvelous new book, Joan FitzPatrick Dean explores the pervasive yet elusive phenomenon of Irish historical pageantry and traces its manifestations over the course of the entire twentieth century. The pageants she discusses were indeed public spectacles, often performed in front of large crowds, in which actors impersonated various figures from the past at pivotal moments in history that were represented consecutively as "the March of the Nation" towards freedom and prosperity (6). Consequently, almost all pageants included a propagandist element. Dean ascribes the apparent reluctance of theater historians to consider pageantry as a distinct theatrical idiom to the fact that such performances often left no script, yet her own extensive archival research has uncovered a wealth of materials that include not only scripts but also programs, production photographs, publicity papers, costume designs, press clippings, and even film footage. The many black-and-white images included in the book give a good sense of the range of these materials and of the scale and splendor of some of the more elaborate pageants, while eight sumptuous color plates illustrate the quality of design that went into the costumes and advertising for some of the more lavish productions.

One thing evident from Dean's study, which should make these pageants fascinating for theater historians, is the extent of the involvement in their production of figures better known to us from the more orthodox Irish theatrical tradition. Fred Morrow of the Theatre of Ireland stage-managed several pageants in the early part of the century. The Gate Theatre's Micheál MacLiammóir and Hilton Edwards devised The Ford of the Hurdles for the 1929 Dublin Civic Week with characteristic adventurousness and, in doing so, managed to combine "expressionistic dramaturgy, stunning design, and sensuous nationalism" (128). MacLiammóir also designed the costumes for the 1935 military tattoo and for The Roll of the Drum, "Ireland's first military stage show" in 1940 (162). Lennox Robinson directed large-scale pageants in honor of St Patrick in 1932 (the year of the Eucharistic Congress and the 1500th anniversary of the saint's legendary conversion of Ireland to Christianity). Edwards and MacLiammóir, again, were pivotal to the successful stage-managing of the 1955 Pageant of St Patrick, which ran to six performances at Croke Park. While the overall message of the piece suggested that the brutality and the gory rituals of the pagans had mercifully been replaced by the peaceful serenity of St Patrick's Christianity, the performance derived much of its thrill from the "frenetic spectacle of pagan depravity" (209), which included slave drivers in chariots brandishing whips, dwarves and a monstrous hunchback dancing grotesquely to discordant music, and bloodstained cages housing sacrificial animals. Hilton Edwards, Brendan Smith, and Michael O'Herlihy were involved in staging the 1956 Pageant of Cuchulainn, which was scripted by Denis Johnston and featured 30-year-old Ray McAnally as the Celtic hero; this pageant also included a gigantic brown bull of Cooley made of papier mâché, with accompanying audio effects to suggest its tremendous roar. The pageants devised by Tomás Mac Anna and Bryan MacMahon for the 1966 commemoration of the Easter Rising were the last of such large-scale historical spectacles.

Dean's study not only provides detailed and evocative descriptions and analyses of the many individual pageants staged over the course of the twentieth century, but also conveys how they reflected their era's political and socio-economic Zeitgeist. Before Independence, pageants were staged by opposing political entities to support their conflicting ideologies: in 1907, for example, the nationalist tableaux of the Gaelic League Language Week Procession competed with the pageant play presented as a charity fundraiser by Lord Iveagh under the patronage of the Lord Lieutenant, which affirmed the political status quo and paid tribute to the largesse of the British aristocracy. In the years leading up to the Easter Rebellion, Patrick Pearse mounted increasingly elaborate and ambitious pageants that promoted "heroic masculinity" (57). The performance of Macghníomharta Chúchulain ("The Boyhood Deeds of Cuchulain") by students of St Enda's school presented the young hero as fearless and "beauteous" (57). (The English translation of the text, by Seán Ó Briain, is included in an Appendix.) Pearse's Lug Lamfada featured over 100 performers and envisioned the Celtic warrior-god as a savior and rebel leader whose victory over Balor was clearly understood as a contemporary metaphor, given that the event concluded with the singing of "A Nation Once Again." Cuchulainnoid war-mongering also featured heavily in the pageants performed in 1910 and 1914 by the pupils of Castleknock College, which showed that oppression could be overcome by physical force combined with Christian virtue. Compared with all this masculine posturing, A Pageant of Great Women staged at Molesworth Hall in 1914 was, inevitably, a more modest affair, even if it starred Constance Markievicz as Joan of Arc in a suit of armor made of linoleum. The newly created Free State had its own agenda: the Grand Pageant of Irish History performed in the late 1920s presented various waves of historical invaders of Ireland but somehow managed to make no reference to the British at all.

Dean suggests that the 1932 Eucharistic Congress heralded a shift away from representations of Cuchulainn and Celtic mythology toward St Patrick and the coming of Christianity, a slant that dominated Irish pageants into the 1950s and increasingly turned them into occasions of faith; this is illustrated by the anecdote that Anew McMaster's performance as St Patrick in the 1954 Tóstal pageant so affected members of the public that "unscripted onlookers rushed forward to kiss the hem of his robe" (204). The militant element previously embodied by Cuchulainn, however, was carried on in the military tattoos created by the Irish Defense Forces in 1935 and 1945. Staged at the RDS where they attracted hundreds of thousands of spectators, they involved as much as a third of the regular army as performers and included demonstrations of modern battle tactics and the use of explosives. The 1935 tattoo culminated in a reenactment of the 1916 attack on the GPO, replicated for that purpose as a large-scale model, which concluded with the building going up in flames. During the Emergency, soldiers also staged smaller shows in provincial towns: these "Step Together" pageants were performed to enhance the military's reputation, present a consistent message about Irish neutrality, and construct a proud Irish heritage.

According to Dean, several factors contributed to the decline of these kinds of pageants. Pageantry lost much of its popularity after the introduction of television in 1961. Mac Anna's 1966 pageant Ainseirí was a last hurrah: it paid tribute to the martyred patriots of 1916—with a spotlight on James Connolly since his life and writings "resonated in the difficult economic circumstances and strike action of the mid-1960s" (227)—as well as to the GAA, the Gaelic League, Fianna Éireann, the Irish Citizen Army, the Irish Volunteers, and Cumann na mBan. Audiences were disappointing. The rise of violence in the North further contributed to the decline of politically or religiously-inflected public spectacles.

In a more recent era, the group Macnas revived pageantry in the context of the Galway Arts Festival. Macnas returned to Celtic mythology for some of the inspiration behind their annual parades, notably for their version of The Táin in 1992, which was also successfully presented at the Expo Festival in Seville, Spain. In their focus on spectacular effects, masks, costumes, and giant puppets, however, the Macnas parades were inspired as much by the European circus and carnival traditions as they were by earlier Irish pageants.

All Dressed Up provides access to and insight into a treasure trove of material that, as the author rightly concludes, reveals the confluence of many tributaries. For that reason, historians, folklorists, anthropologists, musicologists, and historians of theater and of art and design will find much here to whet their appetites. With this book, Joan FitzPatrick Dean has opened a rich vein that invites further exploration by scholars in all these areas of scholarship.