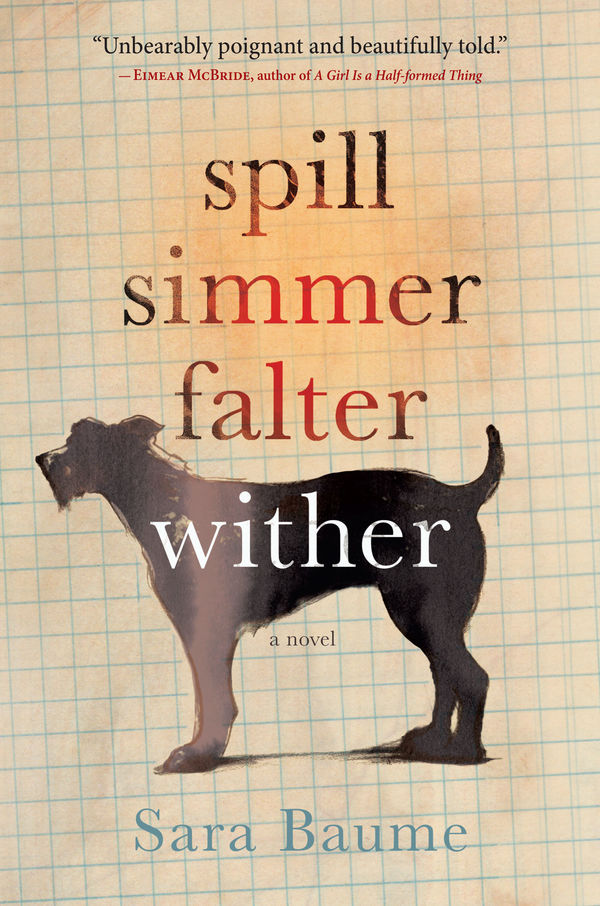

Sara Baume. Spill Simmer Falter Wither. Dublin: Tramp Press, 2015, 216 pp.

Sara Baume’s debut novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither, has been garnering widespread acclaim since its publication last year by the innovative independent Irish publishing house, Tramp Press. Baume’s novel quickly won the 2015 Newcomer of the Year Award at the Bord Gáis Energy Irish Book Awards, the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, and the Hennessy New Irish Writing Award. In a review of the novel, Joseph O’Connor writes, “It’s hard to imagine a more exciting debut novel being published this year. This book is a stunning and wonderful achievement by a writer touched by greatness.”[1] Baume’s novel is indeed a breathtaking piece of work, elegantly structured, and beautifully articulated, and powerfully demands ethical and emotional engagement from the reader, operating almost as a manual in the development of empathetic and environmental awareness.

Spill Simmer Falter Wither is told from the perspective of a 57-year-old man called Ray, an unintentional recluse living in a small Cork seaside town—his house situated in the center of the village, yet his humanity positioned on the edge of community like the coastal setting. Early in the novel he outlines the failures of connection that structure his life:

Everywhere I go it’s as though I’m wearing a spacesuit which buffers me from other people. […] when I pitch and clump and flail down the street, grown men step into the drain gully to avoid brushing against my invisible spacesuit. When I queue to pay at a supermarket checkout, the cashier presses the backup bell and takes her toilet break. When I drive past a children’s playground, some au-pair nearly always makes a mental note of my registration number 93-OY-5731.

They all think I don’t notice. But I do. (14)

And it is Ray’s capacity for noticing that makes this narrative so compelling, rendered even more affective in Baume’s choice of the second person voice.

The entire novel, set over the course of a year, is told in the voice of this lonely man speaking directly to One Eye, a rescue dog he adopts in the opening pages of the novel, equally alone, equally unwanted, who becomes a type of soulmate and doppelgänger for Ray, blurring the boundaries between the human and the non-human animal: “Your photograph is the least distinct and your face is the most grisly. I have to bend down to inspect you and as I move, the shadows shift with my bending body and blank out the glass of the jumble shop window and I see myself instead” (10). This narrative strategy of the second person voice has the effect of both implicating the reader, placing you in the position of a vulnerable and disfigured dog, and registering the narrator’s cautious yet intense desire for connection and communication. It is a highly affective and affecting strategy. This is definitely not a novel for reading in public if you don’t like people to see you sobbing as you experience the tentative emotional connection as it develops, strengthens, and deepens between these two unwanted and unloved creatures who become everything to each other. Baume does vulnerability and emotional attachment dangerously well. If this novel doesn’t cut you open, expose your heart, and teach you empathy, then you are a lost cause. As Leslie Jameson in her book of personal essays on empathy writes, “Empathy isn't just something that happens to us—a meteor shower of synapses firing across the brain—it's also a choice we make: to pay attention, to extend ourselves.”[2] This novel forces us to make that choice, by asking us to spend time with Ray, to notice what he notices, to extend ourselves into his lonely life.

One of the rewards of entering into Ray’s life and mind in the course of this novel is his aforementioned ability to pay close and intimate attention to the world he inhabits. Take this moment, for example:

I haven’t lived high or full, still I want to believe I’ve lived intensely, that I’ve questioned and contemplated my squat, vacant life, and sometimes even, understood. I’ve always noticed the smallest quietest things. A chewing-gum blob in the perfect shape of a pterodactyl. A two-headed sandeel coiled inside a cockle shell. The sliver of tungsten in every incandescent. (43)

What moments like this show you are the richness and beauty of the inner lives of people you might dismiss as strange or odd, as Ray is dismissed by his community. The failure to empathically imagine the lives of such people results in the loss of their unique perspective on the world, their inner moments of beauty. The novel insists on connection, empathy, engagement, and understanding.

Furthermore, as Ray charts these “smallest quietest things” over the course of a year, the reader’s attention is also drawn to the intricacies of the changing seasons of the Irish landscape. In the “falter” (Fall/Autumn) section, Ray notes: “Here’s penny-cress, angelica and a hare over in the field. Stiff as a garden ornament. Now it barrels off, breaks into a succession of long vaults over the stubble of harvested grain, between the bales. Did you see it, did you see the hare?” (124). This demand to look at nature combined with careful detailing of its transformations and cycles is both a testament to Baume’s visual art background (her meticulous way of looking at the world) but also has an ecological underpinning. For as we move through the landscape with Ray and One Eye—sometimes viewing the world from a human perspective, sometimes through the animal’s eyes as imagined by Ray—we are given an intense and intimate appreciation for the environment in such a way as to encourage its protection, sustainability, and conservation; concepts significant in a post-Tiger climate. Importantly, this is a landscape that is evoked in all its beauty, with all its scars, with all its wildness, and all its domestication. Baume asks us to look at this landscape with the same kind of empathy and compassion afforded to the lonely older man and the disfigured, one-eyed dog, asking us to extend ourselves beyond ourselves into the odd, the broken, and the neglected.

Baume details the minutiae of the Irish landscape with such attention that I felt almost unbearably homesick while reading this novel and will re-read it any time I need to evoke Ireland and its contours.

[1] Joseph O’Connor, “Spill Simmer Falter Wither, by Sara Baume: Greatness Already Evident,” The Irish Times, February 7, 2015, http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/spill-simmer-falter-wither-by-sara-baume-greatness-already-evident-1.2094028.

[2] Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014), 23.