The Language that to-day no Irishman may employ in any public service without fine, or penalty, or loss of some kind, shall, in God’s good time, become again—“as sacred as the Hebrew, as learned as the Greek, as fluent as the Latin, as courteous as the Spanish, as court-like as the French.”—Roger Casement, “The Language of the Outlaw”[1]

I think I can state without any fear of contradiction that we, the academic community, are most definitely in centenary commemoration mode here in Ireland. Having survived the horrors of the Great Famine, emerged unscathed from the ’98 celebrations, we have done with the GAA, Conradh na Gaeilge, the Abbey, major political, cultural and literary figures of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, and so on, and, having nearly done and dusted the Lockout, we are now to 1916. The ground work has been set and all of these individual investigations contribute to our improved understanding of what went on to culminate in 1916 in all its intricacies. So many individual people, organizations, and events were central to this dénouement and the significance of each one needs to be meticulously and forensically analyzed. Roger Casement, as a public and private person, his importance at home and abroad, his political profile, his influence in different areas of humanity, presents us with one of the most interesting case-studies of this whole era of Irish history. It is my intention in this paper to explore his introduction to, preoccupation and affinity with, and support for the Irish language and its speakers and promoters throughout his life.

People familiar with the history of nineteenth-century Ireland are aware that there was a heightened awareness of and increasing and expanding dissemination of information about all Irish matters as the century progressed. This manifested itself in many ways: in the establishment of many societies which had initially an academic and antiquarian interest in Gaelic language and literature; disseminating and popularizing that corpus of literature in translated form; exploration of the Irish language in all its iterations in learned circles amongst European philologists; harvesting of Ireland’s folk and musical traditions; the exploitation of Irish literature and history for creative writers in Ireland; and the advance of cultural nationalism.

This all culminated in the foundation in 1893 of the Gaelic League, the aim of which was first and foremost to revive the Gaelic language as the vernacular of the people of Ireland and secondly to create a new literature in that language. Charles McNeill, Secretary, outlines the aims and progress of the League in the following letter at the end of the nineteenth century:

I need not point out the success and influence which have accrued to the Irish language movement since the starting of the Gaelic League about five years ago. There are now upwards of seventy branches of the League spread over the whole of Ireland, as well as numerous branches and affiliated societies in the United States and Great Britain. All these are working earnestly and with one mind towards the same end, namely the preservation and spread of the native language, and the proper recognition of its claims and influence as an element and safeguard of national life and feeling. This conception as realized by thoughtful men is something higher and more powerful than the political nationality, and rises into an atmosphere above the strife of parties. The Gaelic League, accordingly, has drawn within its rank men of the most different religious and political views, and it opens to them a large and fertile field of common labour. It is hoped that all classes will co-operate in a work like this.[2]

In this period also, there was an increasing awareness of Irish history accentuated by contemporary political events including nationalist agitation and increasing cultural nationalism and the production of treatises on Irish history which were more favorable to the native perspective and sensitivities than had been the case hitherto. Growing up towards the latter part of the nineteenth century, Casement, as a literate, intelligent young man, would have been exposed to and would have sought out information about all such matters and absorbed many of the ideas contained therein. Such an education would not have been transmitted through the formal schooling system as, in that system, no reference would have been made to Irish history, language, or culture. The veracity of this is reflected in the following admission from Casement himself: “I was taught nothing about Ireland in Ballymena school—I don’t think the word was ever mentioned in a single class of the school—and all I know of my country I learned outside the school.”[3] Ireland and elsewhere in Europe saw a great awakening of nationalism, an exploration, examination, and articulation of it in all its iterations, benchmarked with other countries throughout Europe and further afield. It was a period of self-discovery with the aspiration of defining one’s future in national and ideological terms. This communication and cross-fertilization of ideas Pan-Celticly and transnationally was aided and facilitated by the rise in literacy and educational outlets, especially in the middle classes where resided the greatest literacy, and also in the concomitant proliferation of newspapers and magazines which promoted and disseminated current ideas and ideologies. This question of literacy, of newspapers and magazines as educational and influential tools, is of utmost importance in the case of Ireland at the time and requires closer scrutiny. Apart altogether from what was available to Casement and his contemporaries in book form relating to all matters Irish, newspapers and magazines, in Ireland and abroad, contributed significantly to the cultural and ideological education of the masses because the end of the century saw an explosion of cultural nationalist printed matter, facilitated in no small part by technological and distribution advances in the printing trade.[4]

As a flavor of what was happening in the Press at the turn of the century, one can cite, for example, the following report in The Nation on February 27, 1897 heralding the soon to be published The Daily Nation:

The principal aim of The Daily Nation will be to arouse the people to a sense of their own rights and to defend these against all assailants. It will be in the highest and truest sense the exponent and upholder of the civic and national liberties of the masses of our countrymen […] The time unquestionably has come when effort must be made to put before the nations of Europe, as well as before the democracies of America and of the Colonies, the supreme national claims of Ireland.[5]

Similarly, Seán Ó Lúing had the following to say about The United Irishman, which first appeared in 1899, in his article “A Revolutionary Journal”:

It is the pioneer Organ of Irish-Ireland […] It is Irish in all things, and is written and conducted solely with a view to Ireland’s interests. It concerns itself with all that concerns Ireland and with nothing else. Its writers include every thinker for Ireland in Ireland or out of Ireland. Its aim is to remake Ireland a reflecting Ireland, a Doing Ireland, a self-respecting Ireland, a prospering Ireland, a Free Ireland. Its motto is, Ireland for the Irish people.[6]

One newspaper in particular, I suspect, did have had a great influence over Casement in his formative years in terms of informing him about Ireland, namely the nationalist Freeman’s Journal and the Weekly Freeman’s Journal. This was the most widely-read newspaper in Ireland in the late-nineteenth century. In support of this notion, Ó Síocháin states of Casement:

In his school days he begged from the aunt, with whom he spent his holidays, for possession of an attic room which he turned into a little study and the writer remembers the walls papered with cartoons cut out of the Weekly Freeman, showing the various Irish Nationalists who had suffered imprisonment at English hands for the sake of their belief in Ireland a Nation.[7]

In this regard, it is also interesting to note in the case of Éamon de Valera that during his youth, “The walls of the [i.e. his bedroom] loft were covered with political cartoons from the Weekly Freeman.”[8] It is also worth noting that the Weekly Freeman stated that it published several of Hyde’s books seriatim and, most importantly:

[…] We assert boldly that it was by the Weekly Freeman bringing them (i.e. O’Growney’s Simple Lessons [easily the most widely used Irish language manual for many years]) before tens of thousands of the youth of Ireland, and placing an easy and effective means of instruction before them, that the progress of the Gaelic League was made possible.[9]

Casement, exposed and influenced by all those information channels, was also very conscious of the impeccable Gaelic pedigree of his native Ulster, as is evident from the following:

Ulster is, in many respects, the most typically Irish province in Ireland. Viewed ethnologically, we find its inhabitants are by origin mainly of Gaelic blood. The Ayrshire and Galloway Scots, who made up so large a proportion of the “plantation” scheme of James 1, were themselves very largely of Gaelic origin, and, in many cases, still Irish-speaking when they landed on the Antrim shores; while the West Highland Islemen, who then, and from a much earlier date, had permeated the coasts of Ulster, taking part against the English in every war of the North, were not only Irish-speaking, but were allied in marriage, religion, a common music and a common poetry, a common ancestry, and a full-shared communion of historic associations with those they came amongst.[10]

In addition to all of the aforementioned, Casement was to connect and interact with that whole coterie of Gaelic-minded people, particularly women, of similar background to himself in N. East Ulster.[11] In particular, Bigger,[12] Ada McNeill, Margaret Dobbs, Rose Young,[13] Alice Milligan,[14] Mary Hutton,[15] and Joseph Campbell are synonymous with what was best in the Gaelic Revival Movement, before it went off politically in a particular direction, and parted company with many of its stalwart, early promoters.[16]

All of the foregoing is ad rem when we first formally encounter Casement in the Gaelic arena in 1904 when he first made his presence felt in those circles. From then on he is a central and important contributor to the Movement not only ideologically, practically, and in terms of generating publicity, but in bankrolling actual Gaelic-related causes. As for his knowledge of Irish prior to that year, very little is known for certain. It is stated that his friend, Robert Lynd, a Gaelic activist and teacher of Irish in the Gaelic League, St. Andrew’s Hall (Oxford Street, London), taught Irish to Roger Casement from 1902 to 1903. We also have the following account of a prolonged immersion in Irish in the Donegal Gaeltacht but no dates are recorded:

Casement too was a lover of the Irish language, which brought him more than once to Donegal, the nearest large Gaeltacht to his Antrim home. A member of our society, Mr. Cecil A. King, when staff reporter some years ago with The Derry Journal, took down the following story from a Master Boyle, who taught at Sleandran, near Buncrana: In Inishowen: When Roger Casement resolved to go to the Gaeltacht to learn Irish, the place he selected was Urris in Inishowen. He walked the whole way from Ballymoney in Co. Antrim, to Lishally, crossed the ferry to Culmore, proceeded over the Scalp, along the old road to Buncrana, and thence through the Gap of Mamore to Urris. Here he spent six months, living the life of the people, hearing and speaking nothing but Irish, and leaving for his home in Antrim with a good working knowledge of the vernacular. He is said to have lodged in the townland of Tiernasligo. He usually wore a “well-ye-coat” (a sleeved waistcoat) made of homespun. In those six months he learned to love the place and the people, laying the foundations of an affection that he retained to the last.[17]

Séamus Ó Cléirigh quotes from a letter written by Casement on March 5, 1904 on the history of Casement’s interaction with the Gaelic Movement:

had not much acquaintance with the Gaelic movement in Ireland until last month when I was fortunate enough to come across, at two country houses (one in Cork, the other in Antrim) I was visiting, ladies in touch with the movement, and from them I learned how deep was the interest growing in this effort to keep alive and extend Irish influences and thought.” The two ladies in question were the Hon. Louisa Farquharson and Ada MacNeill. Casement met Louis […] in February 1904 in Ballyhooly, Co. Cork […] a member and later chief of the Gaelic Society of London.[18]

Louisa Farquharson, a Scottish Gaelic activist, had a great influence over him, as did Ada MacNeill with whom he had close contact ever afterwards. Whatever about the history of his knowledge of the Irish language or his expertise therein, we see in Casement from 1904 onwards one totally committed to and wishing to be involved in the Gaelic League and its ideology and activities. He resembles a religious convert in this respect. True to Gaelic literary tradition, he expresses his love for the language in poetry:

THE IRISH LANGUAGE

It is gone from the hill and the glen,

The strong speech of our sires,

It is sunk in the mire and the fen

Of our nameless desires.

We have bartered the speech of the Gael

For a tongue that would pay,

And we stand with the lips of us pale

And bloodless today.

We have bartered the birth-right of men,

That our sons should be liars.

It is gone from the hill and the glen,

The strong speech of our sires.

Like the flicker of gold on the whin

That the Spring breath unites,

It is deep in our hearts and shall win

Into flame where it smites.

It is there with the blood in our veins,

With the stream in the glen,

With the hill and the heath, and the wains

Shall think it again.

It shall surge to their lips and shall win

The high road of our rights,

Like the flicker of gold on the wind

That the sunburst unites.[19]

Casement’s first public association with the Gaelic League was at Feis na nGleann in Co. Antrim which was held in the summer of 1904. We witness here a public record of his active participation in and promotion of all of the ideals and activities of the League and his association with the main promoters and enthusiasts of the movement, initially in the N.E. of Ireland. The feis was looked upon and promoted by the Gaelic League as an excellent promotional and propagandist tool at local and provincial level feeding the national Oireachtas: “A Feis is one of the most powerful means of working up a living, active interest in the language.”[20] As stated at another feis:

The main object aimed at by the organisers of the Feis was to promote the revival and preservation of the Irish language, to improve Irish literature as far as possible, to excite the enthusiasm of the people in the movement, and generally to induce those who may be apathetic or indifferent, to join the ranks of the Gaelic workers, and give what assistance they could.[21]

The first provincial feis in Ulster was held in Belfast in 1900 and local feiseanna proliferated across the province subsequently.[22] On the committee of Feis na nGleann, Casement was more than actively involved in its execution and success. His involvement with the Gaelic movement increases locally and nationally from 1904 onwards as he makes his presence felt in promoting the language. The effect of Feis na nGleann is recorded thus in an article by “Benmore,” a friend of Casement’s from this time:

Hundreds of young boys and girls were brought into contact with their motherland; the schoolroom became a centre of activity; the Gaelic classes aroused a great interest in subjects that had slept for years. The quaint songs of the Gael took the place of the vulgar productions from overseas. The clash of the camán resounded in every glen, and stout young hurlers were to be seen at play on many a field on the glorious summer days of a dozen years ago. The travelling teacher, in the teeth of wild, tempestuous storms, cycled around the rugged coast of Antrim, between Ballycastle and Glenarm, showering his Gaelic lessons around. The Gael was resurgent in those days in the Glens. Seeds were dropped here and there in those days that will yet fructify and the gleaners of Gaelic Ireland will in other years with a freshness and strength gather the harvest. And now many figures loom up on the horizon of my mind, and pass quickly in succession. Small men and big men, keen thinkers, great workers, grand intellects, men and women who shaped and fashioned a clean Gaelic policy for the children of the North.[23]

From this local espousal of the Gaelic cause, Casement was to progress to the national stage. Douglas Hyde, the father of the Gaelic League and the public face of the Movement, made Casement’s acquaintance in Sligo 1904 at the Sligo feis and a very strong relationship ensued. As Hyde wrote, “Do casadh Ruaidhrí Mac Asmund orm ag feis Shligigh. Ní raibh a fhios agam ar thalamh an domhain cia’r bh é an fear árd áluinn uasal […] do bhí seisean ag cur mo thuairisge féin san am chéadna.”[24] Through Douglas Hyde, Casement initiated his financial support for the Summer Gaelic Colleges, the first of which was established in Béal Átha an Ghaorthaidh, in 1904, a fact recorded by Hyde as he turns down an invitation to attend the opening ceremony for the Munster College in 1904:

I greatly regret that a previous engagement keeps me from attending what will certainly be one of the landmarks of the Irish Language Movement, the opening of the Munster Training College. It would give me great pleasure to be present at the most practical work done yet, from which I expect the greatest advantage to our movement in the near future. The College at Ballingeary, as a piece of selfhelp, will be invaluable as an object lesson. I am glad to be able to enclose a cheque for €5 from Mr Roger Casement, Ballycastle, co. Antrim, which he hopes to make an annual subscription.[25]

Casement’s connection with and financial support for the same College continued for years afterwards and was widely acknowledged and appreciated.[26] His interest in various aspects of the Gaelic Movement and the people connected with them was real, active, and constant. Casement later stressed the importance of the language and the contribution the Gaelic Summer colleges were making towards that end as he indicated in a letter he sent to the Ballingeary authorities:

If ever we let the Irish language die we shall have parted with the foundation stone of Irish Nationality, and, although we may see Ireland a nation it will be a nation lacking the mind, the culture, the colour, the very life-blood of its forefathers. I have just come from a trip through Connemara, and I see everywhere the same evidence of loss of nationality in the decay of language.

If we let it die we shall be a base generation of Irishmen, and those who come after us may well say it was the cowardly and selfish generation of the 20th century that allowed the language to die out. You in Ballingeary, at any rate, are trying bravely, and I hope and pray successfully, to redeem your part of Ireland from that reproach this generation is, indeed, in peril of incurring.[27]

Casement’s connection with, love, and support for one of these Colleges in particular is very important. These Irish Colleges, which were predominantly held during the summer and early autumn when the Irish countryside is at its most appealing, were set up to train teachers for Gaelic League classes, to instruct teachers in modern language teaching methods and to introduce people generally to the Irish language and Ireland’s history and culture in a traditional, Gaelic-speaking milieu. Coláiste Uladh, in the heart of the Donegal Gaeltacht, and all its early history from its establishment in 1906, is central to Casement’s Gaelicism:

These Colleges are very democratic in their composition, and it is one great reason of their charm. Within their walls, as within the Gaelic League, all are equal. A common cause, a common enthusiasm, unites all; young and old, Protestant and Roman Catholic, man and woman. As a rule it means a very rare earnestness and self-denial in the students who devote their one holiday in the year, not to pure holiday-making, but to the attempt to become better acquainted with the language, the literature, the history of their native land, believing that they will be the better citizens for so doing. This is the root idea of the whole Gaelic League: that to the Irish race, the knowledge of their own country, history and language is the one sure foundation on which to build all other knowledge. It is the great idea underlying all educational schemes of the present day in every country; know yourselves. [28]

Casement was to be a great supporter of these Gaelic Colleges in years to come as they were established in the various provinces. Also in the summer of 1904, Casement made a trip or perhaps a pilgrimage to the Aran Islands, long regarded as tobar an dúchais.[29] The Aran islands, from the late-nineteenth century onwards, was the favorite destination and haunt of a great variety of visitors who sought there the last uncorrupted bastion of Celtic civilization. Over the decades they recorded aspects of the life experienced there—linguists, folklorists, anthropologists, ethnographers, photographers, writers, and, especially, the most prominent figures in the Gaelic League who, for many years, frequented the islands as their Gaeltacht of choice. Casement was not impressed by his experience, however, as he communicated to Hyde:

My visit to Galway convinces me (beyond a shadow of doubt, I am sorry to say) that the only hope of the language is in such groups as this of Tawin. The general mass of the Irish-speaking parents have kicked the language out of doors. In Kilronan I heard the fathers and mothers speaking a vile attempt at English to their children—and they with a rich, splendid speech of their own. But there it is! Nowhere did I find the language cared for and, with the exception of Tawin, every Irish-speaking home I entered tabooed the tongue of the parents to the children. It is shameful and almost inexplicable to a man who has traveled as I have among peoples who each and all respect and love their own language. My own countrymen alone are contemptible! For it lies with the people themselves, and if they wished or cared for their country really they could keep her language here in the West, where it is still known and spoken.

Although I nearly despair of the future (I hope I am wrong and only temporarily depressed) of the language, still I feel the very urgency of the situation calls for all the braver effort, and I should be a traitor (like those I am upbraiding) if I allowed my fears to stay my hand or chill my heart. It is only by concentrated action and unremitting and increased effort can any impression be made on the dull, apathetic, dead heart of the Irish-speaking Ireland I have lately seen. [30]

Casement immediately afterwards became publicly involved with what was to become a cause célèbre of the Gaelic League. He wrote to Hyde about the plight of a national school in Tawin, Co. Galway and he, in turn, went on to publicize the matter nationally in a piece titled “The Tawin School: An Appeal from An Craoibhín” that reads as follows:

A chara, I forward you a most interesting letter from Mr. Roger Casement, H.M.’s Consul at Lisbon, in which he tells at considerable length exactly what met his eye in his recent tour through the West—of the pitiable Anglicisation of Kilronan and the coast south of Galway, and of the one little unaided community which he found struggling for their nationality against such tremendous odds. I have never been in Kilronan myself, but I know other parts of the coast, and my own experience entirely corroborates that of Mr. Casement. I made it my business to enquire particularly into the circumstances under which Tawin lost its school, which finally broke up owing to the schoolmistress’s inability to instruct the children in their own language, which the Tawin people insist upon having taught. The school is now a wreck and must be rebuilt. It may seem odd that I should write to you in favour of rebuilding a “National” School seeing how the “National” system has lain like lead upon the heart of the West crushing out of it its very life and soul. But now with the introduction of the bilingual system there is a chance for rational education once again, and Father Kean has guaranteed that if the school be rebuilt no one shall be appointed to it henceforth except someone who will conduct it upon bilingual and rational lines. I have been so much touched by Mr. Casement’s letter that I beg you to print it. We must not allow Tawin to go under in the struggle, or to sink into a Kilronan. I would ask you if you would not open a special fund to rebuild Tawin’s school. If you do, please put my name down for two guineas, and I would appeal to your readers to give what help they can. The admirable actors of An Dochtúir have placed us all under an obligation, and the Tawin people are no strangers to our Dublin branches. I am convinced we shall soon have their school up again for them, and that Tawin will remain one of those places from which we shall draw future inspiration.[31]

The following is Mr. Casement’s letter from Sligo, October 4, 1904:

I am very sorry to miss you at Ratra. I have been in Galway and on Inismór, and then at Tawin on Galway Bay, and coming north yesterday I wired you from Claremorris to say I should go to Ratra tomorrow to see you; later I wired again from Sligo to ask if you were at home, but the telegram came back to say you were in Dublin. I much wished to see you and talk about Tawin—and indeed about Aran, too. There is so much to be done there—much to fight against, and some to cheer up and strengthen. Tawin above all needs a helping hand, and it is of Tawin I would speak and get your advice. I heard of it first from the article which appeared some weeks back in An Claidheamh, praising its brave stand for the language, and then when steaming to Aran I saw its desolate promontory and handful of houses stretched out into the bay. As good luck would have it, on getting back to Galway I found the play An Dochtúir was to be given by the original Tawin Company, with the author himself in the title role, so I stayed over Friday and saw it and met S. O’Byrne and all the Tawin men. Next day, Saturday last, I went out to Tawin and stayed the night there, the guest of O’Byrne at his mother’s house, in the midst of them, and the following day went to the chapel, at Mass, and met the priest, Father Kean.

Well, I heard from Tawin of the loss of its schoolmaster (or mistress rather) through its very stand for the language. The school is empty now, and in shocking repair, and the Board will not send a master until the schoolhouse is put into a fit state. It will grant two-thirds of the cost of repairs, but Tawin (or some other source) must make good the third. Father Kean says that means about £60, the Tawin men think nearer £80, from them. I have not anywhere seen or heard of such a brave true spirit as beats in that handful of poverty-stricken Irishmen and women. They are Irish to the heart, and it did me more good than all else I have seen in Ireland to find them so fiercely trying, in the face of the uttermost difficulty, to keep their own language. They are setting a splendid example to all the rest of the country round, where, although the Irish language lives on the lips of the old, it is not being given by them to their children. Only in Tawin, in all that coast strip, do the parents insist on the children having the language, and they are often being jeered and laughed at by the bigger neighbours round. The loss of their schoolmistress was due to this attitude of theirs and their determination to have the language taught; so that if Tawin goes under in this fight for its own tongue, for my part I see clearly that the days of Irish-speaking in that bit of Galway are numbered. I think every effort should be made to help Tawin—as an object-lesson for the surrounding district. If it gets its school started again the people all around will know that it is due to “the Irish” and to that alone, and Tawin’s brave stand for it, that it has succeeded. The village itself cannot find the sum required. The old men offered, and signed a declaration, to give free labour to help build the school instead of a money grant, but the contractor would not accept that. Father Kean says whenever the sum is subscribed he can start the work, and he can and will insist on a competent Irish teacher going. As things are today the Tawin children are a good four miles from a schoolhouse, and the few that now attend school have to be sent to live near the school, away from their own homes, and when they come home their Irish is going or gone. The mothers and fathers want their own school; where the children will be every day and hour within sound of the old tongue. The young men too hold an Irish school of their own, but in the present wretched building it is a poor business. I have omitted very much I had wished to tell you, but it would be impossible in a letter. I want you to try and help Tawin. I told the people and Father Kean I should do my utmost, for it is a clear case of a community worthy of help. For my own part, I have promised Father Kean to subscribe £20 myself to help the school fund. Could the League not also give Tawin a helping hand? […] I hope the training college at Ballingeary is going on well—it is so badly needed. I fear not very many of the school teachers are the best Irish teachers. There must be better trained teachers. I will send my subscription next year to Ballingeary, please God. But although the schools are a problem, and a stiff one, they are nothing to the homes! It is there in the homes in the West that I fear the cause is lost. The people have no spirit, or knowledge of their past or any hope save “to go to America.” I heard that on all sides. Tawin—poor, brave, fighting little Tawin—is going there too. Some of the young men of An Dochtúir are soon to go—there is nothing for them to do at home. However, the 30 Irish children of Tawin are still at home and to be cared for, and they have the Irish and love it. I saw one thing in a cradle—an infant in arms—and its first intelligible speech is—‘Speak Irish!’ (in the Gaelic, of course. I cannot spell it, or I would put it in its right form). Indeed I heard that injunction in Tawin again and again—it is their motto—their battle-cry all through the countryside—‘Speak Irish!’ Some of the young men are actually sworn on oath not to speak English, and they go all through the country round by Oranmore and Kinvarra, refusing to answer in anything but Irish. But they are only a handful; and therefore I say we should strengthen their hand—and soon too. Well, I have troubled you enough. Do what you can for Tawin—my £20 is ready to help the fund. Surely we can get the £40 to £60 more needed and send it to Father Kean and get the work started. There is ever so much more to be done, but I am not rich, and already I have subscribed to so many things this year I am getting poor! I think were I to live in Tawin or Kilmurry in Aran for three months I should be able to speak the language a bit, and certainly to read it. I can pick up fairly quickly, and in Tawin I found myself able to follow something of what was said around me. Oh, if it could only be made again a living tongue![32]

Here we encounter Casement championing the Gaelic cause, articulating his love for the language, decrying the Anglicization of Ireland, supporting the underdog’s fight for the language. In this cause he became acquainted with Hyde and with Séamus Ó Beirne from Tawin with whom he would have further collaboration in the future in the cause of the linguistic, cultural and physical rehabilitation of the people of rural Ireland.

The year 1904 was the year of Casement’s formal espousal of Irish, the Gaelic movement, the cause of the Gaeltacht. The revival of the language was of paramount concern to him. The Gaeltacht dearest to his heart was Cloughaneely in Gortahork from 1906 onwards when the college was founded there and which was run by and frequented by the great Northern revivalists with whom he was already very friendly.[33] It was, over the years, a haven for all those connected, however tangentally, with the movement:

Gortahork, where Parnell once campaigned, where Maud Gonne rode a charger as she roused the district, where the noble-hearted Casement helped to found an Irish College and which place was in his mind as he sadly noted in his Diary that he saw it from the vessel that was taking him to Norway on his fateful expedition.[34]

The references to Casement’s connection with, contribution to, and support of the College, are well documented.[35] At this remove, it is very hard to imagine the enthusiasm of the people who attended this and similar colleges, irrespective of religion, politics, education, gender, status, and their missionary zeal for the cause of Irish Ireland.

It was the Very Rev. Dr. Maguire who performed the opening ceremony of the Cloghaneely College… The principal was a Miss McNeill, a Protestant native of Co. Antrim. All the bishops in Ulster, Catholic and Protestant, the Moderator of the General Assembly and the Jewish Rabbi, Belfast, were among those invited to the inaugural ceremony.[36]

Over the following years Casement’s name is linked with support for the Irish language and the Gaeltacht, the cradle and stronghold of the language. He is recorded as financially supporting various Summer Colleges, Gaeltacht schools in remote and isolated locations, like the Cruacha Gorma in central Donegal or Rathlin Ireland in Antrim.[37] Casement espoused all efforts to improve the promotion, status, and prominence of the Irish language in Irish society, be it in connection with the appointment of doctors in the Gaeltacht, registering one’s name officially on one’s cart in Irish, the regular inclusion of an Irish article in a newspaper,[38] and so on.[39] This was true also of the great battle to have Irish made a compulsory subject for matriculation in the National University, a very contentious debate in 1909 which stirred up a lot of passions, not least among the Catholic clergy:

Mr. Roger Casement wrote, If the University is not a poor man’s University, it cannot live. The poor Irish student is not ashamed of his country, or afraid of his Language. If the University is to be built up by the Irish people, then the Irish Language must be its foundation stone.[40]

And then latterly:

[…] Is it not a shame and an insult, that while the tongues of Pagan Roman Greece and Rome, and Modern Pagan France will be honoured in the new University intended for the Catholics of Ireland, that the National Language of Ireland which, under God, saved Ireland for the Catholic Church, is to be treated as if it were the language of some wretched tribe inhabiting a West African swamp! Yet, if rumour be but true, this is how a majority of Senators intend treating our National tongue in the new University. Men and women of North Galway, have you no pride and no spirit left, to resent this injury! Have you become like unto a much-belaboured ass, to which an additional blow is a matter of small concern. Evidently so, in the opinion of those wise and learned Senators, who in their wisdom intend providing you with foreign thistles to eat, instead of succulent Irish grass. […] Latin, Greek and Yiddish, Saxon, French and Finnish—All are taught here but Irish.[41]

Wherever Casement appeared and his presence recorded during the years up until his death, whatever activity he was involved with in support of the Irish people in all of its manifestations—humanitarian, economic, military, and so on—the importance of the Irish language was always stressed by him. Over in London on one occasion when he visited an Irish craft fair with his friends—also Irish-Irelanders—he spoke to Pat (The Cope) Gallagher, grandfather of the current T.D. and former M.E.P., who had brought over home-produced articles for display and sale:

Another man was frail with a black beard. The lady was also delicate with silvery grey hair. They came to me. The gentleman with the black beard asked me if I was Mr. Gallagher. I said that I was. “Let me introduce my friends to you,” he said, “Mrs. Stopford Greene, Lord Skerrin, the Honourable Mr. Gibson—Lord Ashbourne’s heir—and my own name is Roger Casement.” They asked me many questions about Donegal, and especially about the Rosses. They knew a hundred times more about the rest of Ireland than I did. They looked at the sports coats and the Limerick lace. Mrs. Stopford Greene was much interested. I am sure that they remained at our stall for nearly an hour. When they were bidding me good-bye, Sir Roger Casement gripped my hand tightly and said, “I have been told you are doing good work for the people. I hope you will not forget the language. Ireland will be lost if she does not preserve her language. Look at Bulgaria to-day—she is the admiration of the whole world, and why?—because she preserved her language.[42]

On another occasion, on a completely different mission, the following is recorded:

Sir Roger Casement inspected Sluagh Lord Edward Fitzgerald of Na Fianna Eireann (Irish National Boy Scouts). […] He congratulated the Fianna on the excellence they had attained in signaling, drill and physical culture. He then gave an interesting account of the Fianna of old, and asked the Fianna of today to emulate their historic predecessors. […] In addition to the training of their bodies, there was the training of their minds in the study of their native language and history.[43]

Even when heavily involved in the humanitarian crusade to alleviate starvation in Connemara, the Irish language is very much in his thoughts in a letter to the editor of the Irish Independent titled “A Noble Effort: Letter from Sir R. Casement”:

Sir, Before your list for the Connemara Islanders closes I should like to say that through the generosity of an Englishman and his family (and some friends here) I am assured of sufficient means to provide the infant children of Carraroe National school with the meal a day, for the next year. I had appealed to Irish men and women to make good for these little kinsmen of ours. While I am indeed grateful to my English friends for their generous and warm-hearted sympathy, I feel that there may be some more Irish people who would wish to be associated with them in so good a work. I have to acknowledge with gratitude a few kindly gifts from Irish friends, and from none more than from one in Canada, who, having read my letter in the Montreal Gazette, says that the first money he has ever earned in his life he ‘wishes to give to his country.’ I am making arrangements so that the money at my disposal shall be laid out to the very best advantage for the purpose in view, and those who may feel disposed to co-operate can do so by sending their contribution to me to the Care of: The Hibernian Bank, College Green, Dublin. Possibly a part of the moneys already subscribed to your journal might be devoted to a similar purpose in the neighbouring schools, two of which, I believe, are in fully as great need of friendly outside help as Carraroe. […]

P.S. The response to your appeal is itself striking testimony to the widespread, national feeling evoked on behalf of the Irish language; for, I think, were your lists of subscribers analysed, it would be found that the vast bulk was made up of those who contributed, not alone for love of the people they wished to help, but for love of the old language those people have so faithfully and so fluently retained. It would be of much interest, I think, to your many readers could you give an analysis of all the subscriptions received in their various sterling categories. […] I think it may be truly said that your appeal has reached the hearts of the Irish people, and that those hearts still beat true for the poor, and true for the old language of this country.—R.C.[44]

Casement managed to convert others to his humanitarian cause aligned with language revival as is evident from the following comments of Mrs. J.R. Green at a meeting of the Irish Literary Society in London:

Meeting of Irish Literary Society, London

She praised Sir Roger Casement’s plan for providing meals for the school children in the middle of the day on condition that the conversation was in Irish.[45] It was a melancholy thing to find in so many quarters a contempt for the Irish Language and the almost absolute indifference in learned circles in England to the oldest and finest Language and literature in the world.[46]

Casement explains his plan further in the Butte Independent:

That is the position of the Irish language in Connemara today—going West, on its long journey, to face the rocks, the cold sea, the wilderness—and die with its face to the wall. I believe the language could still be saved and put on its feet in the West by systematizing more and more the effort begun at Carraroe. There the brightest hour of the school day—that when the children have the pleasant meal, their play, their song and grace in Irish—is identified with the Irish language. And what is working so happily there might easily, and with equal need and equal good, be done in the neighboring schools.[47]

It is worthy to note that when Casement was in Germany trying to recruit Irish prisoners, he met Brian Ó Ceallaigh, the man central to Tomás Ó Criomhthain’s writing Allagar na hInise and An tOileánach. Ó Ceallaigh was to say of that encounter: “He found I knew Irish, talked about the Gaelic League; about Kerry.”[48]

His interest in Irish never waned, despite the circumstances in which he found himself. He was even able to put his knowledge of Irish to practical use during his final imprisonment; according to a letter from his brother to the Irish Independent titled “Roger Casement and Gaelic”:

Sir, When my brother, Roger Casement, lay under sentence of death in Pentonville Prison he was never permitted to see a visitor—relative or friend—without the presence of a warder. Upon the last visit of his nearest relatives he hit upon a plan—nothing less than to hold their conversation in Gaelic. This was done, the warder, an Englishman, not understanding one word of the glorious language! So that Roger Casement’s last words and messages were given in the language he so dearly loved. A signpost he was instrumental in having erected in this beautiful spot—the Gaelic letters standing out boldly—has been cut down by order of some bigots. […] It is an insult to the true Ireland to hold up to scorn the language of the Gael.[49]

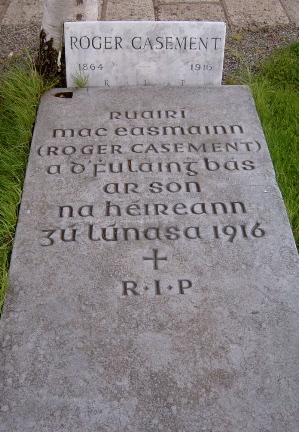

It is difficult for us here in the twenty-first century to appreciate how strongly the Irish language resonated with the Gaelic League enthusiasts at the beginning of the last century, how committed they were to its survival and active in its promotion. Casement was intimate with such people for many years, moved in their circles, followed and supported their causes, and, in particular, was spiritually, intellectually, ideologically and emotionally driven by its aims and objectives. He subscribed to and fully endorsed Yeats’ sentiments delivered in New York in 1904: “I hope we will all live to see the day when Irish will again be spoken in Ireland to the exclusion of all other tongues. The Gaelic language will be a barrier to the vulgarity and coarseness which is today the plague of Ireland.”[50] It is fitting that the Irish language is prominent on his gravestone.

[1] In the preparation of this article, use was made of the very helpful and exhaustive research published over the years. I mention in particular: Séamas Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary (Lilliput Press: Dublin, 2008); Séamus Ó Cléirigh, Casement and the Irish Language (Clódhanna Teo: Dublin, 1977); Eamon Phoenix, Pádraic Ó Cléireacháin, Eileen McAuley & Nuala McSparran (eds.) Feis na nGleann: a Century of Gaelic Culture in the Antrim Glens (Stair Uladh: Belfast, 2005); Ríona Nic Congáil, Úna Ní Fhaircheallaigh agus an Fhís Útóipeach Ghaelach (Arlen House: Dublin, 2010); Angus Mitchell, “An Irish Putumayo: Roger Casement’s Humanitarian Relief Campaign Among the Connemara Islanders, 1913-14,” Irish Economic and Social History, 31 (2004): 41-60; Diarmaid Ó Doibhlin, “Womenfolk of the Glens of Antrim and the Irish Language” in Seanchas Ard Mhacha/Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, 16, no.1 (1994): 103-124.

[2] Charles McNeill, “The Gaelic League,” letter to the editor, Tuam Herald, Mar. 11, 1899.

[3] Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement, 12.

[4] Casement would have been well aware of The Peasant, The Leadar, The United Irishman, Sinn Féin, Ulaidh, Gaelic American, and other periodicals. It is very interesting to explore the range of newspapers and magazines that formed the staple diet of Casement and his contemporaries. It is also of note that Casement financially supported some of these productions. See Ó Cléirigh, Casement and the Irish Language, 27.

[5] The Nation, February 27, 1897, 1.

[6] Seán Ó Lúing, “A Revolutionary Journal,” Leader, Jan. 26, 1952, 21-23.

[7] Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement, 14.

[8] The Earl of Longford and Thomas P. O’Neill, Eamon De Valera (London: Arrow, 1974).

[9] Nollaig Mac Congáil, “Saothrú na Gaeilge ar Nuachtáin Náisiúnta Bhéarla na hAoise seo Caite: Sop nó Solmar?” in Réamonn Ó Muireadhaigh, ed., Féilscríbhinn Anraí Mhic Giolla Chomhaill (Dublin: Coiscéim, 2011) 144.

[10] Casement, “The Irishry of Ulster,” letter to the editor, The Nation, October 11, 1913.

[11] Diarmaid Ó Doibhlin, “Womenfolk of the Glens of Antrim and the Irish Language,” Seanchas Ard Mhacha/Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society 16, no.1 (1994): 103-24.

[12] Guy Beiner, “Revisiting F.J. Bigger: A Fin-de-Siecle Flourish of Antiquarian-Folklore Scholarship in Ulster,” Béaloideas 80 (2012): 142-62.

[13] For further information about Rose Young and her involvement with Irish, see the introduction to: Diarmaid Ó Doibhlin, Duanaire Gaedhilge Róis Ní Ógáin: cnuasach de na sean-amhráin is áille agus is mó clú (Dublin: An Clóchomhar, 1995).

[14] Catherine Morris, Alice Milligan and the Irish Cultural Revival (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012).

[15] Mary Anne Hutton (1862-1953) is remembered mainly for her poetic translation of the Táin. See “Hutton, Mary Anne,” http://www.ainm.ie/Bio.aspx?ID=259.

[16] At the beginning of the last century, the Gaelic Language and League numbered among its supporters some of the most influential and public figures in Irish society. Among them was W.B. Yeats: see, for example, the following (translated) excerpt from An Claidheamh Soluis, the Irish Nationalist newspaper: “Public Meeting at Kiltartan. Among those who attended were Mr. Edward Martyn, Lady Gregory, W.B. Yeats […]. Mr. W.B. Yeats said that a few years ago the cause of the Irish language seemed to be a lost cause. He had heard people singing London music hall songs of the vulgarest kind in a Connacht fishing village, 18 miles from any town. He was told that those who sang them thought it proved them to be better educated than their neighbours, who only sang the beautiful old Irish songs. But now, owing to the work of the Gaelic League, the pride was beginning to be all on the other side. Those that had the Irish were beginning to be proud of it, and to remember that the stories and songs it contained were their greatest possession, and those who had no Irish were beginning, like himself, to learn it. […] If we allowed Irish to become forgotten or even debased, we would look foolish in the eyes of the world. […] Every nation had its own duty in the world, its own message to deliver, and that message was to a considerable extent bound up with the language. The nations make a part with one harmony, just as the colours in the rainbow make a part of one harmony of beautiful colour. It is our duty to keep the message, the colour which God had committed to us, clear and pure and shining; An Claidheamh Soluis, July 29, 1899, 314-5. See, also, George Moore’s views on the Irish language, well-publicized at the time: “[…] but it will be our fault if our children do not learn their own language, for I am convinced that it profits a man nothing if he knows all the languages in the world and knows not his own”; Moore, The United Irishman, March 3, 1900, 5.

[17] Cecil A. King, “Some Casement Associations with Donegal,” Donegal Annual/Bliainiris Thír Chonaill, 7, no. 1 (1966): 59.

[18] Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement, 213.

[19] Roger Casement, Ulster Herald, Aug. 19, 1916.

[20] An Claidheamh Soluis & Fáinne an Lae, Jul. 13, 1901.

[21] Fáinne an Lae, Sep. 19, 1898.

[22] This from the Freeman’s Journal: “FEIS ULADH—On Friday evening, 14th inst., there was held a meeting of this committee, which has been appointed by the Belfast branches of the Gaelic League to superintend the preparation of the Feis Uladh, or ‘Ulster Festival’ which will take place in Belfast towards the end of November. The objects of the Feis will be the encouragement of Irish literature, music, and industries, to effect which it will offer prizes for literary works, hand-writing, singing and recitation, all in the Irish tongue; for Irish step-dancing, Irish choir and solo singing; ancient Irish geography, harp and pipe music, Irish art, designs etc.; see Freeman’s Journal, Sep. 18, 1900.

[23] Ulster Herald, Aug. 12, 1916.

[24] Hyde, Mise agus an Connradh (Dublin: Oifig Díolta Foilseacháin Rialtais, 1937), 125. “I met Roger Casement at the Sligo feis. I had no idea whatsoever who this tall, handsome gentleman was. […] He was asking about me at the same time.”

[25] Southern Star, Aug. 21, 1909.

[26] See, for example, the following points made by Seán Ó Floinn in his letter to the editor for the Irish Independent: “Sir—Most of your readers know of the associations of the late Roger Casement with the Sinn Féin and Irish Volunteer movements and the 1916 Insurrection. His keen interest in the Irish language movement as far back as 1905 may not be as well known as it deserves to be. Below I give the contents of a letter written by Roger Casement on August 23, 1905, to the late Rev. Professor Richard Henebry, D.Ph., the well-known Irish scholar from Co. Waterford who was professor of Irish at University College, Cork, from 1909 to 1916. The letter was written from ‘The Savoy, Denham, Uxbridge, England.’ It was found by me recently in a book that belonged to the late Dr. Henebry. The following is the text of [the] letter. ‘Dear Dr. Henebry, I hope you found your friend Mrs. Stopford Green at the Gresham. I was very sorry to leave Ireland and fear it will be some time before I can get back. I hope you will be in Ireland then and that I may be able to visit the Irish school at Ballingeary, Co. Cork. I send you an article of mine on the Irish language question written in a Belfast quarterly in May last some of the quotations of which may interest you. We must all try and fight for the language this winter, and leave no stone unturned to help teachers and scholars. This address will always find me. I may be abroad in a month or two.—Sincerely yours, Roger Casement.’ The letter reveals a warm friendship between Roger Casement and Dr. Henebry, and between them and Mrs. Stopford Green and shows Roger Casement’s interest in the Irish language movement eleven years before his death 3rd August, 1916. Dr. Henebry died on St. Patrick’s Day, 1916”; Ó Floinn (Carrick-on-Suir), “Casement and the Language,” Irish Independent, April 14, 1938.

[27] Casement, Irish Independent, Apr. 20, 1914. This was written the occasion of laying the foundation of new building of the Munster Training College.

[28] Casement, Sinn Féin, Sept. 16, 1911.

[29] Tom Casement, Roger’s brother, also spent some time in the thirties on Aran, no doubt retracing his brother’s visit there at the beginning of the century. Mentioned by Ria Mooney in Breandán and Ruairí Ó hEithir, eds., An Aran Reader (Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1991): 239-42.

[30] An Claidheamh Soluis, May 11, 1904, 6; quoted again in editorial of Leader, Nov. 12, 1904.

[31] Ibid.

[32] An Claidheamh Soluis, November 5, 1904. For a fuller account about the Tawin controversy, see: Nollaig Mac Congáil, “Fíoradh na Físe Gaelaí? Bunú Choláiste Thamhain Céad Bliain Ó Shin: Stair Chorrach” Journal of the Archaeological and Historical Society, 62 (2010): 157-85, https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/1414/Com.2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[33] We can see Casement aligned and ad idem with this constituency in the following reported title “The League in Ulster: Proposed General Conference” in An Claidheamh Soluis , September 2, 1905: “On Friday of Oireachtas Week an informal meeting of some of the Ulster Delegates to the Árd-Fheis was held in Barry’s Hotel, Dublin, for the purpose of devising some scheme for the consolidation of the working units in the North, with a view to the more effective propagation of the aims and principles of the Gaelic League. There were present: Miss Mac Neill, Cushendun House, Cushendun, Miss Lavery, Belfast; Miss Mac Crudden, Belfast; Miss Alice Milligan, Rev. Fr. Greenan, Co. Down; Rev. M. O’Mullin, Carndonagh, Co. Donegal; Rev. J. O’Doherty, Derry; Rev. Fr. Maguire, Donaghmoyne; Mr. Stephen Gwynn, Mr. Roger Casement, Mr. Richard Bonner, Townnawilly, Donegal; Mr. John King, Newcastle; Mr. Seamus Mac Manus, Mountcharles, Co. Donegal; Mr. Ward, Omeath; Prof. Mac Laughlin, St. Columb’s College, Derry; Mr. P.J. Flanagan, Derry; Mr. J. Bonner, Barnesmore, Co. Donegal; Mr. J.J. O’Hegarty, Derry; Mr. Cahill, Co. Down and Mr. Tierney, Monaghan. Mr. Stephen Gwynn presided. The position of the Movement in Ulster generally was discussed, and proposals were put forward for the amalgamation for the whole province of the Toome conference, at present operating in the North East, and the Ulster Union of the Gaelic League, working in the North West, the objects of both of which are practically similar. […] The following resolutions were unanimously adopted: that the secretaries be requested to issue along with their summons the sketch of an agenda paper covering the following points for discussion: 1. the formation of an Ulster Training College. 2 the creation of a machinery for the organization of Ulster 3. the cultivation of the Irish tongue and literature in Ulster.”

[34] MacDara, “Beyond the Mountains,” Ulster Herald, August 29, 1902.

[35] See, for instance, Séamus Ó Néill & Bernárd Ó Dubhthaigh, eds., Coláiste Uladh: Leabhar Cuimhne Iubhaile Leith-Chéad Blian 1906-1956 (Donegal: Coiste na Coláiste, 1956), 11. They note that Úna Bannister was a frequent visitor to Gortahork and earnestly participated in the College activities to the extent that we find her composing poetry (in English) there–a common occurrence among staff and students there and being mentioned in another poem there; see 11 and 17. “Tháinig Úna agus Eilis Bhainistear as Sasain a fhoghluim Gaedhilge”; 14. “Dhá nó trí bliana a bhí an Choláiste ar bun nuair a thoisigh Ruaidhrí Mac Easmuinn ar shuim a chur san obair. Thug sé fa deara go raibh an teach ar an Ardaidh Bhig ro-bheag don mhéid mac leighinn a thigeadh gach bliain. Bheartuigh sé ar halla a thógáil a bheadh ina aionad [sic] foghluma do lucht na Coláiste sa tSamhradh agus ina ionad cuideachta agus caidreibh do mhuintir na paróiste ar feadh na codach eile den bhliain. Chuir sé a lámh ina phóca féin agus fuair sé congnamh airgid óna chairde”; 11. A record of a speech by Agnes O’Farrelly published in the Ulster Herald (27/8/1921, 3) records “[…] the pleasure and the satisfaction of Roger Casement when he saw the new building he had initiated so that the College might be suitably housed—that and his keen interest in the life of the place.” The College is materially represented by a neat stone building acquired by the generosity of Sir Roger Casement; see Sinn Féin, Aug. 23, 1913, 3. “D’fhan pioctúir an fhir chaoil aird thigeadh de shiubhal cos trasna Chill Ulta as an Fhal Charrach ‘un na Coláiste go soiléir ina n-intinn”; Ó Néill & Ó Dubhthaigh, Coláiste Uladh, 17. “Bhí suim mhór ag an fhear uasal Ruaidhrí Mac Easmuinn i nOideachas dhá-theangach, agus gach bliain nuair a thigeadh sé go Cloich Cheann Fhaola, bhronnadh sé suim airgid ar scoltacha dhá-theangacha na paróiste le duaiseanna a thabhairt do na scoláirí a b’fhearr Gaedhilg. Sa bhliain 1912 bhronn sé leabhar ar gach príomh-oide de na scoltacha seo. Tá ceann de na leabharthaí seo i seilbh an sgríbhneora agus ní scarfadh sé léi ar ór nó ar airgead. ‘Dánta Staireamhla na h-Éireann’ is tiodal dí. Ar chionn de na dánta tá ‘Cath na Binne Boirbe’ a chum Ruyaidhrí Mac Easmuinn é féin. Cheartuigh an t-ughdar in a láimh-sgríbhinn féin, mion-dhearmaid cló thall ‘sa bhfos ‘sa dán seo’; ‘Ag Fágáil Sláin.’”; ibid., 69.

[36] Pádraig Ó Baoighill, Cardinal Patrick O’Donnell (Donegal: Foilseacháin Chró na mBothán, 2008), 260.

[37] “Casement also gave strong support to the effort to bolster Irish on Rathlin island, Co. Antrim. From 1904 on he made regular payments to the Rathlin Teacher’s Fund”; see Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement, 552, n.46.

[38] Ó Cléirigh, Casement and the Irish Language, 23-25.

[39] This refers to the famous case taken by the Gaelic League on behalf of Niall Mac Giolla Bhríde recounted in his Dírbheathaisnéis Néill Mhic Ghiolla Bhrighde (Dublin: Brún agus Ó Nualláin, Teór., 1938): 97 ff.

[40] Meeting of Gaelic League in Galway regarding Irish as a compulsory subject for matriculation in NUI, “Irish in the National University,” Connaught Telegraph, Jan. 2, 1909.

[41] “The Boycott of Irish,” letter to the editor, Tuam Herald, Jan. 30, 1909.

[42] Patrick Gallagher, My Story (Dungloe: Templecrone Co-Operative Society: 1939, 203-4).

[43] Butte Independent, Apr. 15, 1914.

[44] Casement, “A Noble Effort: Letter from Sir R. Casement,” Irish Independent, Jun. 26, 1913.

[45] The condition that food would be provided with an Irish language stipulation echoes what happened during the Famine when a change of religion was a prerequisite for being fed.

[46] Connaught Telegraph, Mar. 2, 1914.

[47] Letter from Roger Casement, Dublin April 17, 1914, Butte Independent, Jun. 20, 1914.

[48] Ó Síocháin, Roger Casement, 410.

[49] Agnes Casement-Newman (Co. Antrim), “Roger Casement and Gaelic,” Irish Independent, Jul. 15, 1924.

[50] Quoted in Robert Mahony, “Yeats and the Irish Language Revival: an Unpublished Lecture,” Irish University Review, 19, no. 2 (Autumn, 1989): 220 f.