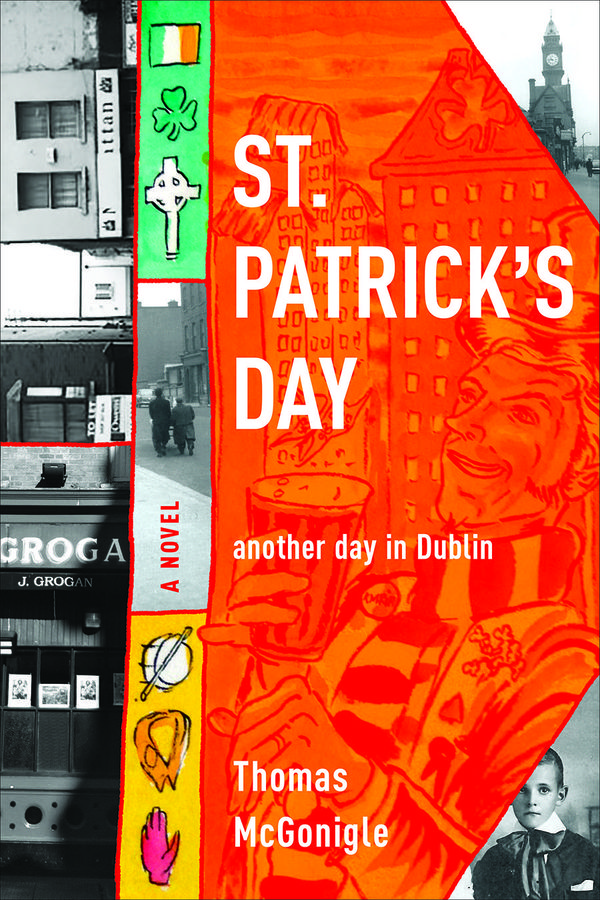

Thomas McGonigle. St. Patrick’s Day: another day in Dublin. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2016, 244 pp.

Winner of the Notre Dame Review Book Prize, Thomas McGonigle’s third novel St. Patrick’s Day: another day in Dublin, offers a quasi-comprehensive depiction of the teetering stacks of memory. An Irish American writer recently bereaved of his father, gallivants around a half-remembered Dublin on a wet, sordid St. Patrick’s Day: in other words, “[t]he self-absorption of a small country” (127). In swimming, modernistic prose, McGonigle takes the reader on a sodden journey of Dublin all the while studying its claims to a literary landscape and the uncanny familiarity of geographical memories.

Born in Brooklyn to Irish parents, McGonigle’s time as a student in UCD in the 1960s informs the simultaneity represented through the prose. Flitting almost imperceptibly between the past and the present, across Dublin, Europe, the world, the resurfacing memories of the protagonist decoupage the seedy and somewhat sad reality of his present. The complexity of national identity is explored in the mutually-informing strictures of both Irish and Irish-American cultures: the most ardent symbols of Irishness on the ostensibly the most “Irish” of days, is actually a product of American culture. Likewise, the high priests of Irish culture, James Joyce in particular, were saved by American influence. While uprooted Irish-American families struggle to reconcile the hybridity of their identity, Tom muses that the streets of Dublin are empty in the evening, “with all the people tucked into suburbs stuffing themselves on the American dream” (39).

St Patrick’s Day takes from other Dublin stories. While Joyce’s Dubliners and Ulysses are the clearest influences, there are also shades of J. P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man and Brian O’Nolan’s At Swim Two Birds. The Ulyssesian impulse to record an entire day intact is admirable but McGonigle’s novel has little of the warmth or good-natured humor of Joyce’s work. The shades that haunt the characters of this work flit like memories in an altogether less disorientating and more realistic stream of consciousness than is to be found in some of Joyce’s more experimental works. Similarly, the experimental nature of a work that seeks the reproducibility of Joyce’s method, feels fittingly worn out, tired, done. The poppy love story that bolsters Ulysses is here replaced with an altogether more muted and sad affair. At times, Joyce himself appears as one more shade of the work: characters speak with an uncanny similarity to Joyce’s. McGonigle captures the ways in which the literary styles of Gabriel Conroy, Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom can lodge in the mind of the reader and spew unbidden as one traces their Dublin steps.

While the hat-tip to Joyce is initially most notable, there are also a number of striking resemblances to Samuel Beckett’s early collection of short stories, More Pricks Than Kicks. The protagonist of St. Patrick’s Day is highly reminiscent of Beckett’s character, Belacqua, a melancholic ne’er-do-well who vacations between the class strata of Dublin’s inner city. The excesses of Beckett’s pre-war modernistic prose meld well with McGonigle’s. As a body explores the city, the body too is mapped with a kind of scatological relish. Indeed, what is striking about St Patrick’s Day is the widening gulf between Irish modernism and the modern Irish moment. Like Joyce’s Ulysses, the novel commemorates the cities and times of its creation—“Dublin-Sofia-New York / 1972-2015” (238). And, like Ulysses, the work is conducted along an ever-meandering stream of consciousness, one that registers not only the simultaneity of place-memory but the way in which past memories resurface in the present.

The work is thoroughly modernistic but this emphasis on modernism serves to highlight the very distant memory of this mode of writing. Much of the novel takes place in the present day in Grogan’s, a stubborn and beloved pub on Dublin’s South William Street. While Grogan’s may once have been the epicenter of many a debauched night, nowadays South William Street is a hub of urban creativity: cocktails, nightclubs, hip restaurants and the middle-class neo-arts-and-crafts haven that is the Powerscourt Shopping Centre. These new institutions of an urbane, European capital and their modern millennial attendants are nowhere to be seen in McGonigle’s pages. Instead, St. Patrick’s Day presents a Dublin—and an Ireland—steeped in misogyny, loss, and trauma. The Dublin of Tom’s experience is perverted by memory; while it may very well chart the experiential disorientation of one person’s experience of the city, unlike Joyce’s Dublin, there is little familiar to the modern reader. McGonigle demonstrates the ways that geography intrudes upon the intimate and personal mind but also the corresponding manner in which personal experience may obscure the very space in which we exist.

As such, memory is the beating pulse at the heart of the novel. The most poetic moments of the novel are often provoked by reflections on the mysterious powers of memory: at one point the narrator thinks “[m]emory is a moth-eaten blanket and now the year is turning chilly” (176). The elegance of McGonigle’s writing is most evident in these moments but (as with thought proper) soon the book has lurched to some more jarring detail. In pursuit of simultaneity, like the “Aeolus” chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses, McGonigle includes all manner of paratextual paraphernalia in St Patrick’s Day: headlines, bylines, reproduced comics, extensive quotations in jarring fonts, blank pages, and in perhaps the most impressive reproduction, a cheque to the author for 500,000 Irish punts from the poet Derek Mahon. The multimedia of the work bridges the modernistic techniques and brings it in line with a dizzying postmodern aesthetic of rupture. One has the feeling that other stories are yet buried within these asides though without the firm footing of a realist narrative, the effort to recover them feels ultimately frustrating.

While McGonigle’s novel is ostensibly about Ireland, it is an irrecoverable notion of Ireland that feels at once jarring and familiar. The front cover testifies to this: a tricolour, a Celtic high cross, a shamrock, the red hand of Ulster, a Lambeg drum. While these may once have been the symbols of a complex island-of-Ireland identity, they now disturb a quiet if uneasy peace. It is unclear how they reflect the present moment but to consign them to the past feels similarly eerie. In the very porous nature of national or collective memory, McGonigle’s novel confronts the now-overlooked symbols of a recent Irish past.

St Patrick’s Day addresses other uncomfortable realities too: the Dublin and its Dubliners are real, visceral, and abject. Vaguely sick and sickening in turn, the novel is preoccupied with the mores of the physical body. Like Gulliver, Tom cycles between relishing the human body and finding it intolerable. The narrative voice pores over the frankest of human frailties with a strange and vaguely-nauseating glee. Nowhere is this more evident than in the copious discussions of female bodies. Women’s bodies are derided, spilling over the pages in brutal and dehumanized terms. A rather tedious example involves a cruel, off-hand joke about TB and VD. “Dreary,” thinks the narrator, but that does not quite go far enough. Echoing the humiliation of women’s bodies in Swift’s, Joyce’s, and Beckett’s works is one thing but the novel also reveals the complicity of the reader in such instances; “Like most women back then, she did not do anything. She was just around. The men did what had to be done” (84). There is patent humor in such an observation but the obvious misogyny is difficult to cast aside. Whether this vicious streak is by calculating design or merely the byproduct of a citywide overexposure to a misogynistic Irish culture in which the narrator basks, the aftertaste is bitter all the same.

St Patrick’s Day is clever and weaves a strandentwining tale. With pithy reflections, elegant prose, and moments of penetrating insight into modern Irish society, there is yet a bitter and unpleasant reality at the novel’s core that makes it difficult to read and to digest. McGonigle is surely to be admired for the scope and breadth of this work but without quite achieving the warmth of Joyce or the comedy of Beckett, the cruelty rankles and the novel slogs where it might otherwise sing.