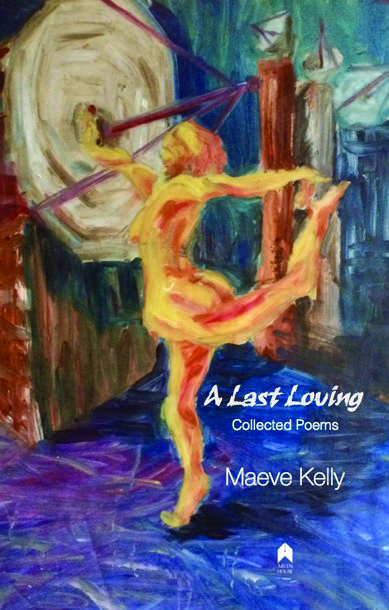

Maeve Kelly. A Last Loving: Collected Poems. Dublin: Arlen House, 2016, 146 pp.

The title of Maeve Kelly’s collected poems, A Last Loving, comes from a piece late in the volume, “Elegy for Mary Catherine.” As its name suggests, the poem memorializes a dead loved one, but it leaves the cause of Mary Catherine’s death and her relationship to the speaker ambiguous. Its final stanza declares, “Our forces gathered in a last loving, / with candle and with psalm / obliterating the silence and the dark / making our arms her catafalque” (120). The mood of these lines encompasses grief, quietude, and insight into other people born of fierce affection, and it captures much of the tone of this volume. Through poems that reflect intensely on personal experiences and individual relationships, Kelly portrays the adversities women encounter in Ireland. Her collection both records her own life and depicts the diverse challenges facing Irish women in their struggle for equality.

A Last Loving compiles two previously published collections, Resolution (1986) and Lament for Oona (2005), along with a substantial section of new and uncollected pieces. Unlike other omnibus volumes, the collection adopts a reverse chronology. Its newest poems come first, followed by the previously published works. In such a deeply personal and biographical volume, the movement backward in time produces a memorable experience for the reader. After traversing over a hundred pages of poetry, we stumble across Kelly’s authorial anxieties in “If I Forget” (112). We encounter her daughter, Oona, first as a lost loved one, before walking through Kelly’s fresh and savage grief in Lament for Oona, before finally progressing to her affection and hope for her young daughter in Resolution. The effect is painful, but invariably intimate.

In a brief but comprehensive introduction to the volume, Vivienne McKechnie and Jo Slade outline its major themes: feminism, family, loss, old age, and the natural world (11-13). In particular, McKechnie and Slade emphasize the importance of Kelly’s “commitment to writing in pursuit of social justice and women’s liberty” (11). As a founding member of a battered women’s shelter in Limerick, Kelly has made these issues central in her life and in her art. In addition to her poetry, she has published two novels, a novella, and three collections of short stories, all of which engage with feminist concerns. These prose works have received greater critical attention for their political perspectives, but her poetry also reflects a lifetime of passionate advocacy for gender equality.

While the earlier poems of Resolution deal most explicitly with the political cause of feminism (three pieces in that collection are entitled “Feminist”), her newer poems eloquently address the domestic and communal restraints placed upon women from a range of perspectives. Particularly subtle and moving pieces deal with the often-overlooked value of “women’s work,” and the frustrating trade-off between artistic and domestic labor. These poems are made more urgent by the consciousness of aging, loss, and time. Of these later works, two poems particularly exemplify such nuanced reflections on artistic legacy and gender equality: “Table Cloth” (19) and “Love” (25).

True to its title, “Table Cloth” focuses on an actual tablecloth, embroidered lovingly by a grandmother or great-grandmother present only in a picture on the wall. After a meal accompanied by boisterous political debate, during which “Her subtle artistry is here ignored,” the speaker removes and cleans the cloth: “After the meal I wash and starch / her love’s memorial. I fold and put away / the linen shroud that is her art. / I store in cupboards all she had to say” (19). The power of the poem lies in its shuttling between reverence for this object of beauty, regret at those “New generations” unable to appreciate it, and discomfort with a society that restricted women’s influence to the sphere of hand-crafts. Through this poem, we are made aware of Kelly’s own power to speak and memorialize this voiceless ancestor.

Yet A Last Loving reveals that Kelly’s own poems are the products of intense struggle, as she makes clear in “Love” (the first of four poems so titled in this volume):

I embraced these chains.

Their spikes tore me.

You need food,

Therefore I cook.

I need order,

Therefore I clean.

My poems lie unborn

on my unmade bed.

Whereas Kelly’s love for her family is palpable throughout her work, here, that affection becomes a form of bondage—a source of reasonable, necessary responsibility, which the speaker welcomes while acknowledging that it denies life to her artistic offspring. The “unborn” poems, the “unmade bed,” reflect the painful disorder—internal as well as external—that such conflicting goods can produce.

Such personal meditations characterize the tone of A Last Loving, preoccupied, as its title suggests, with love and its inescapable companions, fear and loss. Nonetheless, Kelly is occasionally goaded to outrage by the suffering and injustice inflicted upon subordinated women. A particularly shocking poem, “Jessie’s Song,” tells the story of a woman abused by her husband and traumatized by electroshock therapy: “Jessie shakes all over now / since they did that thing, / since they took electric wires / and plugged them to her brain” (48). The poem’s painfully upbeat ballad meter keeps the rhythm of the speaker’s indignation. Here, anger is the natural result of compassion for an abused and neglected woman.

While rooted in personal experience and replete with vibrant imagery, the collection’s verbal intricacies occasionally spin off into disorienting abstractions. Such is the case in “Scribe,” wherein metaphors of carpentry and dance compete to define the process of the poetic life, giving way to a catalog of gruesome images of which, as the speaker concludes, the “poem says nothing” (22). The invocation of concepts like “love-death” and “Life-decay” compounds the confusion of the reading experience. Bewilderment may be the intention here, but the effect is ultimately distracting. Nonetheless, even “Scribe” concludes with an elegant and memorable image. Its penultimate stanza declares, “This is the furnace around which I dance, / its heat teaching me the balance / even the planets must practice” (23). “Scribe” thus serves as a microcosm of collection as a whole. In spite of its occasional vagaries, A Last Loving is characterized by vivid imagery like the dancing planets, the embroidery of “Table Cloth” and the unborn poems of “Love.”

Little has been written about Kelly’s work—most of the available commentary consists of decades-old reviews, which generally treat her prose works alongside several other novels. This volume is a powerful example of the need to redress this scholarly neglect. A Last Loving offers readers a corpus of rich, nuanced, and intensely personal poetry, testifying to the diverse experiences of Irish women who frequently navigated adverse social conditions. One hopes that the collection ignites new scholarly conversations, not only in response to Kelly’s feminist advocacy, but also in recognition of her powerful poetic voice.