Just four years after the end of the Second World War, in his 1949 essay “Here is New York,” E.B. White begins his celebration of the city with the promise that “On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.”[1] In her biography of Maeve Brennan, Homesick at The New Yorker, Angela Bourke takes her cue from White in describing Brennan as “an expert in both loneliness and privacy.”[2] There is a marked tension between privacy and public visibility and obscurity and celebrity in Maeve Brennan’s writing, an anxiety that speaks in significant ways to the concerns of the mid-century Irish woman writer and to the position of women during the years of the American war effort. While Brennan is perhaps best known for her association with The New Yorker magazine through the 1950s and 60s and beyond, her concern with celebrity and public performances of different kinds was also shaped via the formative influence of another New York magazine in the 1940s: Harper’s Bazaar.

Brennan served an important apprenticeship at Harper’s Bazaar from 1943 to 1949, one that would prove to be a significant influence on the “Long-Winded Lady” essays she contributed to “The Talk of the Town,” a popular corner of The New Yorker. Her years at Harper’s Bazaar played an especially important role in shaping her thinking about celebrity and style, and I am especially interested in the ways in which celebrity and fashion in New York magazine culture in the period interact with the responsibilities of magazines committed to playing a role in the war effort of the 1940s. Brennan was witness to a period of fascinating contradictions, during which the fashion industry and its attendant machine of celebrity had to negotiate anew the terms of its relevance and importance for its American readership while women at the center of the war effort were granted a new visibility in the public celebration of their contribution to public life.

What appears to be a sustained interest in the tensions between privacy and public visibility in Brennan’s work is all the more intriguing given that one perception of her is that of the celebrated mid-century icon—as the popular mythology would have it, the figure who inspired Truman Capote’s Holly Golightly. The carefully styled figure who appeared in Karl Bissinger’s portrait of Brennan, taken around 1948, is one of the most famous impressions of the writer. What emerges very clearly from Bourke’s account of Brennan’s life in Homesick at The New Yorker is that she was a writer who was, at one time, a personality capable of holding the attention of New York society. At the same time, a number of her stories and, in particular, a number of her Long-Winded Lady essays published in the 1960s, display a sustained anxiety and ambivalence about celebrity and visibility, one that I wish to argue might be explained by the obstacles faced by the Irish woman writer in the period. It can also be understood as an effect of Brennan’s alertness to the different publicly visible archetypes of Irish women in the United States, most notably the Irish woman servant, or “Irish Bridget” as she was caricatured by popular nineteenth-century magazines, a recurring figure in her stories set in the fictional New York suburb of Herbert’s Retreat.[3]

In one of Brennan’s Dublin stories entitled “The Clever One,” first published in 1953, a young girl makes the mistake of declaring to her sister that she would like to be an actress, only to find her ambitions severely cut down to size:

“When I grow up,” I said to Derry, “I’m going to be a famous actress. I’ll act in the Abbey Theatre, and I’ll be in the pictures, and I’ll go around to all the schools and teach all the teachers how to recite.”

I was about to continue, because I never expected her to have anything to say, but she spoke up, without raising her head from her necklace. “Don’t go getting any notions into your head,” she said clearly.

I was astounded. Where had little Derry picked up such a remark? I had never said it, and I was not sure I had ever even heard it. Who had said it to her? I was astounded, and I was silent.[4]

This is a scene in which a small child unwittingly acts on behalf of the greater “common good,” as enshrined in the Irish Constitution’s promise to defend the life of women in the domestic sphere.[5] Her intervention has the effect of thwarting her sister’s ambition to take up the most public of roles and she ventriloquises all manner of Irish patriarchal Urtexts in the firm rebuke “don’t go getting any notions.” Brennan was all too aware of the hazards that attended female ambition—most particularly the ambitions of the aspiring woman writer. Her years at Harper’s Bazaar offered their own insights into other new and challenging ways in which women were taking up roles in the public sphere that mirrored the anxieties generated by the publicly visible woman artist exposed in “The Clever One.”

I will begin by considering how Brennan’s years at Harper’s Bazaar magazine offered exposure to the idea of celebrity in its different forms in ways that are refracted in her later writing and imbricated in the experience of the Irish woman audacious enough to entertain “notions” about pursuing a writing life and determined to exert control over the presentation of her own image in the public sphere.

Brennan was in post at Harper’s Bazaar as a copywriter and later as an associate fashion editor under the editorship of another Dublin woman, Carmel Snow, who ran the magazine along with fashion visionary Diana Vreeland during a time when it launched a number of new Hollywood faces. Vreeland and Snow were celebrities in their own right who had a seismic impact on New York magazine culture in the period. Vreeland would eventually leave her post as Fashion Editor at Harper’s Bazaar to become editor at Vogue. One of the most notable of the new faces discovered during the Snow-Vreeland years at Harper’s Bazaar was Lauren Bacall, who first appeared in Harper’s Bazaar in 1943, the very year Brennan started work at the magazine. So important was the magazine’s role in discovering Bacall that Life magazine reported on it in a special feature published two years later:

Her first Harper’s Bazaar picture appeared in a blouse layout in the February 1943 issue. Actresses Martha Scott and Margaret Hayes were photographed on the same page, and by luck Betty was identified as “Betty Becall, young actress.” Despite the misspelling this was a fateful moment, for out in California both the picture and the name were noted by the willowy Mrs. Howard Hawks. She remembered them when the March issue of the magazine arrived, with Betty’s face on the cover.[6]

In the early 1940s, while maintaining its commitment to lifestyle and fashion editorials, Harper’s Bazaar also worked hard to persuade its readers of its role in serving the larger public good in a time of world conflict. In October 1942, on the 75th anniversary of the magazine, it offered a statement to readers reassuring them that it was, more than ever, a magazine that aspired to be “A Repository of Fashion, Pleasure, and Instruction.”[7] During the years of the war, Harper’s Bazaar comprised a fascinating, often contradictory textual blend of fashion features, housekeeping advice, and literature; alongside articles about style, advertisements for cosmetics, celebrations of women and the war effort, and editorials on the responsibilities of the American housewife to hold down the fort, the magazine published poems and stories by W.H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Langston Hughes, Rainer Maria Rilke, as well as—and this must have been of special interest to Brennan—work by Liam O’Flaherty, Mary Lavin, and Elizabeth Bowen. The same editorial policy saw the work of literary authors published alongside features on fashion and cosmetics. The culture of the magazine at the time seemed at ease with the apparent ironies of including items about fashion, household management, and etiquette and conduct alongside features like, on one occasion in 1946, a profile of Jean-Paul Sartre by Simone de Beauvoir, “Jean-Paul Sartre: Strictly Personal—A Profile of the Most Talked-About Writer in France Today.”[8] Brennan was fully immersed in the life of the magazine with all of its inherent contradictions in its textual blend of “Fashion, Pleasure, and Instruction,” and her work at Harper’s Bazaar led to her own early encounter with celebrity in a turn of events that was revealing of her place in New York society and in New York magazine culture.

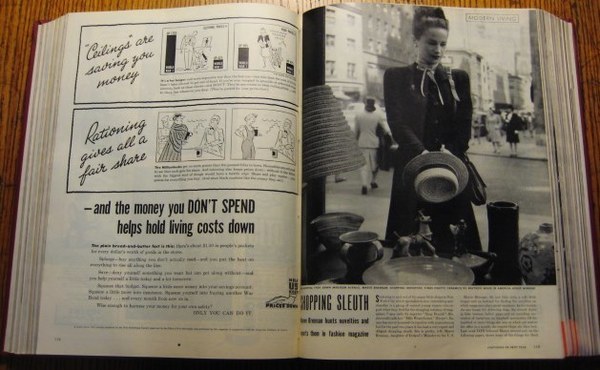

In May 1945, Life ran a story entitled “Shopping Sleuth: Maeve Brennan Hunts Novelties and Reports Them in Fashion Magazine,” an article that was keen to emphasize both Brennan’s Irishness and her family connections in Irish and American politics:

Scurrying in and out of the many little shops in New York City which specialize in new, interesting merchandise is a group of earnest young women who report what they find for the shopping columns of magazines. Vogue calls its reporter “Shop Hound.” Madamoiselle calls her “Mlle Wearybones.” Harper’s Bazaar has never honored its reporter with a pseudonym but for the past two years it has had a very expert and diligent shopping sleuth. She is pretty, 5-ft. Maeve Brennan, daughter of Ireland’s Minister to the U.S. Maeve Brennan, 26, has blue eyes, a soft Irish brogue and an instinct for finding the novelties on which magazines place great emphasis. In her rounds she sees lamps for delousing dogs, the newest styles in false bosoms, ladies’ pipes and an unending succession of variations on standard accessories. Of the hundred or more things she sees or which are sent to her offices in a month, she reports those she likes best. Last week LIFE followed Maeve around and, on the following pages, shows some of the things she liked.[9]

What follows is a carefully styled photo essay by celebrated photographer Nina Leen, a series of photographs that capture Brennan at work examining accessories and objects of interest that would presumably find a home in recurring features such as “Shopping Bazaar,” and which placed Brennan at the center of an emergent postwar consumer culture. The lighthearted tone of the essay stands in stark contrast to the seriousness of the material that frames it, which includes a call to service that cautions, “Be sure a Nurse is there when Your Man needs her!”[10] and an article containing devastating revelations about atrocities in Europe entitled “The German Atrocities—Capture of the German Concentration Camps Piles Up Evidence of Barbarism that reaches the Low Point of Human Degradation.”[11]

Several pages are dedicated to what amounts to Brennan’s own fashion shoot, a profile that would have been sure to raise her visibility in New York society. In a number of the photographs, Brennan appears to model different accessories, but elsewhere her gaze is very determinedly turned away from the camera and fixed on the garment or object under examination (see figures 1a, 1b, and 1c). As early as 1945, Brennan found herself an object of considerable interest—on the other side of celebrity.

By the time Karl Bissinger came to photograph Brennan in the late 1940s, capturing what would become one of the best-known images of the writer, Brennan was on the verge of graduating to The New Yorker (fig. 2). Brennan’s years as a fashion assistant served a purpose in the creation of a particular kind of mise-en-scène and aesthetic in the way she presented herself to the camera. Bourke notes that the apartment of theater critic Thomas Quinn Curtiss was the carefully chosen setting for the portrait.[12] The picture could have been taken from a fashion editorial for Harper’s Bazaar and presents Brennan surrounded by books, objets d’art, and the trappings of New York sophistication. The portrait by Bissinger canonized Brennan alongside other writers and actors photographed in the making of Bissinger’s oeuvre. A collection introduced by Gore Vidal, The Luminous Years: Portraits at Mid-Century by Karl Bissinger, presents Brennan’s portrait as part of a body of work that features writers such as James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Carson McCullers, Colette, and Brendan Gill, as well as personalities such as Montgomery Clift, Katharine Hepburn, Alec Guinness, Marlon Brando, John Wayne, John Ford, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.[13]

The power of such images and the celebrity they conferred was especially important to Harper’s Bazaar in the 1940s, as stars of stage and screen served a particular purpose in advancing an often not-so-subtle ideological agenda. The January issue of 1943 featured a particularly confused State of the Union address about what American women should aspire to be in times of conflict:

We cannot label 1943. We cannot proceed by signposts. Harper’s Bazaar meets the New Year with a program subject to change because the life of women is changing, and fashion is not fashion unless it is current history. As we adjust ourselves to ration cards, servantless houses, meatless Tuesdays, and manless everydays, we begin to think in new terms of the way we want to look—Be Yourself, says this issue, Be Indestructible, Be Indispensable, Be Uprootable…and to this we add a fifth—Be Unforgettable. Come Hell or High Water, we must clip to our overalls, paste to our mirrors, this principle: Our real job is to remain women…first, last, and forever.[14]

Hollywood stars were often drafted in as epitomes of such aspirational values. The aforementioned editorial carried the reminder:

Katharine Hepburn has never been anything but herself, independent as the Fourth of July from the day she was born. She washes her own red hair, plans her own clothes, shoulders her own wherever she is going. She is on Broadway now in Without Love, and will be seen soon with Spencer Tracy in Keeper of the Flame, a new film.[15]

The article was accompanied by a photograph of Hepburn looking particularly resolute, determined to live up to these promises. In April of the same year, the magazine offered further “instruction” on how to be an American woman, one mediated again via the Hollywood star system, when Harper’s Bazaar killed off “The Old Glamour Girl” with considerable vitriol to make way for the “New American Look”:

She has gone, let her go, God bless her. She was good in her time, but now she’s a has-been […] a limbo-bimbo. She stemmed from the first Garbo pictures; she grew into a composite caricature of three movie stars and one debutante—Garbo, Dietrich, Crawford, and Brenda Frazier. The Veronica Lake witchlocks that covered the country in a mass formation finally tipped the scales.[16]

The “New American Look” marked a very clear departure from the “Old Glamour Girl” in how it defined American femininity. The New American Look was launched with an accompanying promise that the clean lines of the new style “expresses a way of being […]. She’s come out from behind the blinders of hanging hair, she’s thrown away her ego.”[17] It is a vision of virtue and morality presented as far superior to the Old Glamour Girl and this new ideal of American femininity corresponded with the need for a new seriousness on the part of the luminaries of film and fashion so that celebrity without virtue became an object of suspicion.

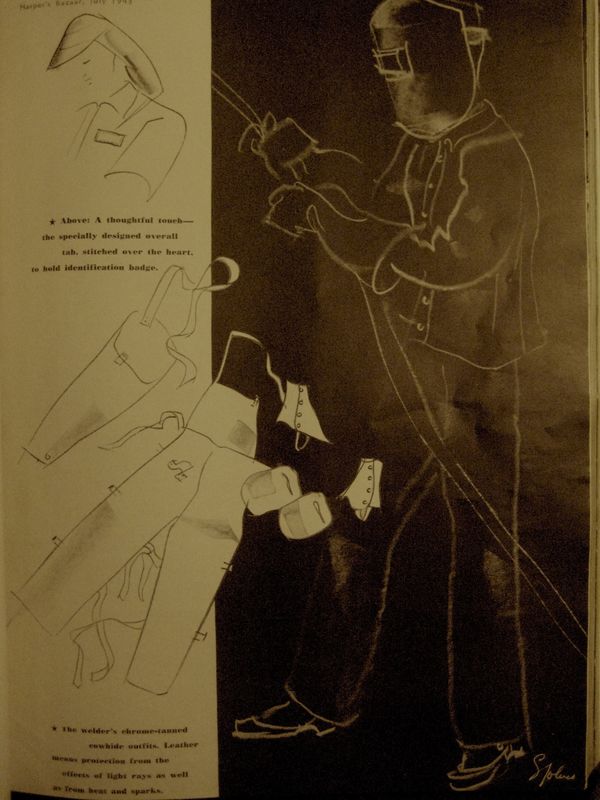

The inculcation of such coded value systems was to become a recurring feature as Harper’s Bazaar staged particularly revealing interventions during the war years and transmitted unmediated messages about the responsibilities of American women during the war effort, whether in going to work in munitions factories or on the land. The magazine celebrated and censured its American readership in turn. The same often took the form of the celebration of women in the work place, as in an extended feature on “The Women Who Serve,”(fig. 3)[18] a series of profiles of women in active service; this feature was complemented in the same issue by “The Best Dressed Women in the World,” published in July 1943, which presented a series of sketches of land and munitions workers as a rival to the more recognizable fashion editorial:

You’ll find them on scaffoldings…in turnip fields…on trucks…in assembly lines…welders and farmers and riggers and assemblers, working coast to coast, three shifts a day, equipping the men overseas. These sketches of the neat, sound, snappy gear of our women war workers were made at the Brooklyn Museum’s Exhibition, “Women at War.”[19]

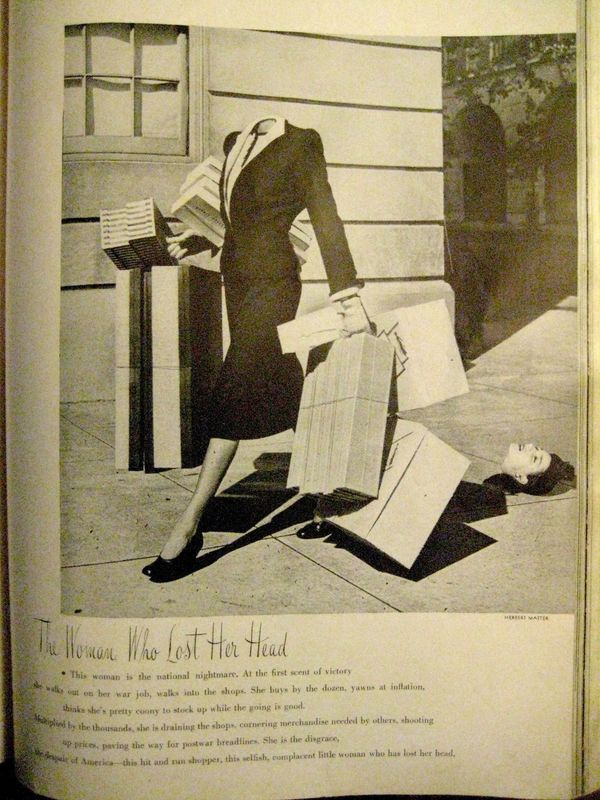

In September of the same year, the magazine issued a public service announcement in the form of a severe and curiously anti-consumerist indictment of “The Woman Who Lost Her Head” (fig. 4):

This woman is the national nightmare. At the first scent of victory she walks out on her war job, walks into the shops. She buys by the dozen, yawns at inflation, thinks she’s pretty coony to stock up while the going is good. Multiplied by the thousands, she is draining the shops, cornering merchandise needed by others, shooting up prices, paving the way for postwar breadlines. She is the disgrace, the despair of America—this hit and shop runner, this selfish, complacent little woman who has lost her head.[20]

Thus, the confusion of “Fashion, Pleasure and Instruction” so central to the magazine’s philosophy led to the production of articles and editorials on consumerism, celebrity, and responsibility that were in many ways at odds with each other.

Such mixed messages were not confined to the material published in fashion editorials, also finding expression in the advertisements of popular brands such as Pond’s and Cutex. Pond’s Cold Cream was an especially visible brand that placed monthly advertisements in Harper’s Bazaar throughout the war years. The campaign featured the fiancées of soldiers who were themselves cast as a new kind of celebrity, raised up from the ranks of, but also representing, women active in the war effort. It ran with the tagline “She’s engaged! She’s lovely! She uses Pond’s!” One version of the advertisement introduces “Anne Nissen, Gallant Bride-to-be of a Soldier” and explains that “Her engagement to Lawrence Van Orden was announced by her parents shortly before ‘Larry’ went into the Army.” The advertisement is made up of various elements including a photograph of the young woman’s engagement ring and continues:

Anne is in uniform, too—the trig overalls-and-blouse girls in defense plants all over the country are wearing. “I couldn’t have Larry do all the fighting,” Anne says. “I wanted to do my share.” She is in a big munitions plant—employing 1,000 women. She works on rotating shifts—7 a.m. to 3.30 p.m.—3.30 p.m. to midnight or midnight to 7 a.m. Anne says, “In a war plant you work indoors and with intense concentration. This begins to show in your face if you’re not careful. Your skin gets a tense, drawn look. I’ve always used Pond’s Cold Cream. It helps keep my skin feeling so soft and smooth, and it’s a grand grime remover when I get home”(fig. 5).[21]

Pond’s wasn’t alone in exploiting the public celebration of women in the war effort. An advertisement for Cutex deployed a similar device. It produced a special edition shade of nail varnish labelled “On Duty” for women going to work in munitions factories and hospitals and celebrated:

Clever hands, Ready hands. Hands at work. Millions of them in hospitals and offices, at machines in our great war plants. For them, a new nail polish: On Duty, by Cutex, an unobtrusive shade for war work. It is shown here on hands at a drill press at the Delahunty Institute (fig. 6).[22]

At the higher end of the fashion scale, Chanel promised “service to beauty” in an advertising campaign that seemed to see no contradiction between the interests of the beauty industry and the war effort (fig. 7).[23]

Maeve Brennan made her own contribution to telling the story of the war effort when the magazine published a short essay in June 1943 called “They Often Said I Miss You.”

The essay imagines women writing to their sweethearts on the battlefield and charts the change of the rhythm of their letters as time passes. It begins:

The first letters all said good-by; that is good-by again. The girls who stood in stations watching the tail of a train disappear around a corner began to write their letters even before the sound of the departing whistle died away. All the way home, urgent phrases, suddenly important, flickered through their minds. They put down quickly all the things they had meant to say and didn’t, all the things they had tried to say and couldn’t.[24]

At first glance this might seem a rather sentimental take on the predicament of sweethearts separated by war, but its apparent naivety belies a more sophisticated interest in the piece in the narrative technique that is such an important feature of Brennan’s later published work. The essay reveals an interest in memory and the function of narrative that speaks to Brennan’s mature writing, and most particularly to the dispatches of the Long-Winded Lady for “The Talk of the Town.”

The pressure to arbitrate between the demands of the fashion and beauty industry and its attendant cultures of celebrity and the serious responsibilities of magazines to support the war effort dissipated the moment the war ended in 1945, and the magazine suddenly became full of anxiety about what might be considered the “notions” that women might have developed during the war years. It took up its mandate to offer instruction as well as pleasure with new vigor. An essay, “The New Spirit,” published in April 1946, is especially revealing in this regard:

Today there is a new way to be beautiful (and at once it becomes the only way), animated by a new spirit, and born of a new need. The woman of this country is neither a man’s competitor, nor his comrade—but his complement, his complete-ment. He has come out of the war with a heightened sense of himself as a man, and a disquieting sense that the American dream girl isn’t altogether a dream. In his mind the girl who is one of the boys is a dead duck; the girl who is out to out-smart the next fellow is a dead pigeon; and the “busy-signal” girl, with so many appointments that during one day she is already halfway to the next, is the deadest of all. He wants a woman to be the beautiful, desirable, leisurely creature who restores him and gives him peace. She must look it. The new spirit of appearance is beauty with the man in view.[25]

Brennan bore firsthand witness to the changing currency of celebrity in its different forms in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar in the 1940s—from the fate of women who starred in advertisements for cold cream, to the vilification or valorization of stars of the stage and screen for different ideological purposes, to the sudden rise in visibility of women at work, and to the subsequent restoration of the status quo. It perhaps comes as little surprise, then, that Brennan’s later writing displays a deep interest in, but considerable ambivalence about, celebrity in its different forms.

In several of Brennan’s essays for The New Yorker’s “The Talk of the Town” feature, the idea of public visibility and celebrity is placed under pressure, and privacy, obscurity even, often takes on a new value, offering necessary self-protection from public opinion and the all-too-predictable hazards encountered by the woman writer.

It is this concern about the publicly visible roles taken up by and imposed upon women in the period that makes Brennan proceed with caution around ideas of publicity and celebrity.

The Long-Winded Lady’s musings on the nature of celebrity are brought about by direct or oblique encounters with Julie Andrews, Elizabeth Taylor, Greta Garbo, and Marilyn Monroe, to name a few. Such encounters usually give rise to a real sympathy for how public visibility both opens the door to ridicule—not least to that accusation of having “notions”—and is potentially detrimental to the private, interior life of the writer. The same anxiety is particularly distressing to the Long-Winded Lady, for whom quiet reflection and going unobserved is an occupational requirement as she records scenes from New York life, and all the more so given that the Long-Winded Lady’s dispatches were published anonymously in the first instance.[26]

In an essay published in 1963, the author-narrator observes a scene in a bookshop in which a man makes gloating comments to his sniggering companions about Marilyn Monroe. Monroe died in 1962 and the Long-Winded Lady is clear in her feelings about such crassness: “I took off my glasses to get a look at them. Cruelty and Stupidity and Bad Noise.”[27] She turns this scene, this hurtful attack on Monroe, into a one-act morality play in which the abstract figures of Cruelty, Stupidity, and Bad Noise mishandle Monroe’s memory and are censured by the Long-Winded Lady. The Long-Winded Lady’s sympathy for the suffering icon is revealing of a larger interest in the chasm between private and public life on Brennan’s part, and Monroe is a figure deserving of particular sympathy. Thomas Harris notes the exploitation of Monroe’s personal history in the making of the cinematic myth:

If the film makers, with publicity support, typed Grace Kelly as the ideal mate, they accomplished with equal effectiveness the establishment of Marilyn Monroe as the ideal “playmate.” It was the playmate image which, nourished by the acceptance of her pictures, skyrocketed her to an almost allegoric position as the symbolic object of illicit male sexual desire. The nature of the image was a natural outgrowth of Miss Monroe’s pre-movie experience as a model and cover girl of “girlie” magazines.[28]

In Brennan’s work, encounters with personalities from stage and screen offer a gateway for meditation on matters of privacy and self-revelation that are important to any writer, but most particularly for a writer as intimately autobiographical as Brennan. Wherever publicly celebrated icons appear in Brennan’s work, they more often than not trigger an inquiry into questions about subjectivity and the hazards of public visibility. In spite of at one time owning her own place in New York celebrity circles, Brennan is deeply ambivalent in these later essays about such visibility and the hazards of public display versus the sanctity of private life.

A number of her essays are most interested in self-display of the more immediately recognizable kind—in the form of the Hollywood Star. The encounter with Marilyn Monroe is accompanied by references to Greta Garbo, Elizabeth Taylor, and Julie Andrews, to name a few. “The View Chez Paul” (1967) describes an uncomfortable encounter with Julie Andrews at the Algonquin Hotel and imagines New York as an ever-moving film set occupied at will by “the moviemakers”:

They annex what they want—this doorway, that second-floor window, a corner of the park, a certain stretch of street—and they ignore the rest, including us New Yorkers, who stand about smiling and goggling like friendly natives. The moviemakers hate to be asked questions. They hardly seem to see us. They are aloof, touched by the remoteness of the Star that will begin shining now at any minute. They wait. And, on the outside, we wait—adults, children, and dogs, all of us crowding as close as we can get to where the Presence will stand, the Star. The Star on West Forty-Fourth Street today was Julie Andrews.[29]

The Long-Winded Lady, too, is keen to get a glimpse of “the Star,” but is embarrassed when Andrews catches her looking at her as she eats lunch: “At the sight of me, Julie Andrews froze in fury. Behind her sandwich, she was at bay, her hungry face glazed with anger.”[30] That she is fascinated by the sight of Andrews caught in the mundane act of eating a sandwich is a reminder of the chasm between the powerful and carefully maintained veneers of the Hollywood star and the ordinariness of their mortal lives.

Elsewhere the Long-Winded Lady is moved to explore her own relationship with celebrity in directly revealing terms in a scene prompted by her being mistaken for the film star, Mary Astor:

I like seeing movie stars as I go on my way around the city. I like recognizing them and knowing who they are and knowing that by just being where I am they make me invisible—a face in the crowd, another pair of staring eyes. I never jostle movie stars, or ask them for autographs, or try to snip locks of their hair, but I do stare. I feel that by recognizing them I have earned the right to stare, and I also feel that they do not really mind. It is different if you are not a movie star. One time I was mistaken for a movie star. Then, when the mistake had been cleared up, I was stared at for not being a movie star.[31]

The Long-Winded Lady’s calling card is her anonymity, her role as outsider, sympathetic chronicler of the emotional crises, embarrassments, and disappointments of others, so being taken for a movie star is an unexpected turn in the narrative. Being mistaken for a celebrity and then being the focus of resentment for not being a celebrity is a rare turning of the narrative gaze directly upon the Long-Winded Lady, and one that leaves her perturbed: “It was all my fault. I had been anybody, but now I was only not somebody. I left the restaurant in a hurry, without having any coffee.”[32]

That this case of mistaken identity gives rise to anxiety is a clear hint at a greater ambivalence in Brennan’s work about public visibility. Soon after this incident where the Long-Winded Lady is made to feel “not somebody,” she has a different kind of brush with celebrity, one that gives rise to a new moment of sympathy. In one scene we see her observe Elizabeth Taylor and Laurence Harvey at work on a film set in New York: “Elizabeth Taylor was at the wheel, and Laurence Harvey sat beside her. During the pause before she started the car again, Elizabeth Taylor glanced into the rear-view mirror and pushed idly at her dark hair, which was tousled, using her left hand.”[33] Thoroughly preoccupied with their own image the Hollywood stars are made to film the same scene over and over:

They went through their scene several times—many times—racing the car backward, stopping, and racing it forward again. It was really a very cold night. People kept coming to watch and then drifting away. At one point, a policeman came and put up a barrier in front of me. I looked around. I was the only person behind the barrier.[34]

There is something comical and clownish in this performance, as the stars are forced into a seemingly redundant repetition, with the Long-Winded Lady as a faithful audience and witness.

The Long-Winded Lady goes on to describe how she is disturbed by a dream in which she revisits the same scene, one in which Greta Garbo is cast in a special role. Garbo was one of the “Old Glamour Girls” banished by Harper’s Bazaar in 1943 and mythologized in popular culture for her retreat from the world, but in the Long-Winded Lady’s dream sequence she appears at the height of her fame and power:

I am standing on the corner of Eighty-sixth and Fifth, and across the street, on the opposite corner, Greta Garbo is standing, surrounded by bright lights and big cameras. She is wearing an enormous fur hat that does not hide her splendid face. Where I am, it is dark. […] A policeman comes and puts up a barrier in front of me. I look around. I am alone. I am all the crowd there is. I am the crowd. I watch Greta Garbo, and I roar like a crowd. My enthusiasm gets the better of me and I howl. In a matter of minutes, I am a mob. I press forward to get a better view of Miss Garbo, and then I make a wild surge. The barrier comes down with a crash. Policemen arrive and form a cordon to hold me back. […] I begin to cheer. I am almost out of control. I seem to be turning into a riot, but reinforcements of police arrive and I quiet down.[35]

That the Long-Winded Lady here appears as a one-woman fanatical riot seems to serve to emphasize the mania of the Hollywood star system as the ultimate machine of celebrity. The dream ends with a melancholy walk up Madison Avenue and the speculation that she may cross paths with another star: “Maybe Alec Guinness will be the one who will not see me.”[36] The name of Alec Guinness is not the only echo of what might be thought of as “home turf” for the Long-Winded Lady.

If Life magazine insisted on making an asset of Brennan’s Irishness in its 1945 profile, in her essay “A Shoe Story,” the Long-Winded Lady is reminded, on overhearing strangers discuss John F. Kennedy, that she was born in the same year as the President-To-Be, in 1917: “They were talking about Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy. […] I was aware from reading the papers that Senator Kennedy and I were born the same year, but the close connection between us had never been apparent to me until that moment.”[37] “A Shoe Story” was published in 1960, the year in which Kennedy became President, and the emphasis on the “close connection” between them is a reminder of Brennan’s family connection to Irish-American political life and its relationship with the idea of celebrity, particularly given John F. Kennedy’s iconic place in the Irish-American constellation. The same year marked the end of the decade that saw two other Irish-American icons lay claim to their place on the Hollywood walk of fame: Maureen O’Hara’s defining role in The Quiet Man, and Grace Kelly’s rise to stardom, both of which must have made an impression on Brennan, although they are notable by their absence in the various encounters with celebrities recounted by the Long-Winded Lady.

The period immediately after Brennan graduated from Harper’s Bazaar to The New Yorker saw developments that placed the Irish firmly in the center of American celebrity power structures. Just a year after the John Ford’s The Quiet Man offered a new reading of Irish-American relations, in August 1953 Life presented a very different statement on the influence of Irish culture in American life in a special feature dedicated to the designs of Sybil Connolly, heralded by the magazine as an Irish invasion of the New York fashion world. The article celebrates the arrival of the designs of Sybil Connolly in New York, and the accompanying fashion spread very clearly takes inspiration from The Quiet Man, featuring as it does models in báinín tweed posing in different West of Ireland settings. The images are a clash of American fashion and rural Irish life—one model poses on a village street while a passerby looks on, curious, and the caption reads simply, “Cyclist on main street in village of Trim is going to milk cows.”[38] Brennan’s earlier cameo appearance in Life magazine would by the 1950s be superseded by the rise of a new interest in Irish style and celebrity on American shores.

Set against these investigations of public visibility of different kinds, Brennan’s Long-Winded Lady is always alone at the restaurant table from which she observes her subjects. Brennan’s work offers a particularly compelling if subtle take on the anxieties of self-declaration and its attendant visibility. A 1974 interview with Time magazine offers a reminder that remaining unseen and even invisible is a professional requirement for the Long-Winded Lady: “Maeve Brennan is one of those people who love New York ‘because the chances for being invisible are so much greater.’ Small and given to wearing dark glasses, she spends much of her time looking and listening, with only an open book for camouflage: ‘Nobody has ever noticed that I never turned the page.’”[39]

That the same anonymity and invisibility would seem a safer position from which to write is perhaps further explained by what some of her stories imagine as the staging of Irishness in the United States and the misappropriation of the idea of exile by the sometimes all-too-visible, self-serving male Irish artist. In Brennan’s 1952 story “The Joker,”[40] we encounter Vincent Lace “our Irish poet” in America. Lace emerges as the down-at-heel version of previous Irish writers celebrated in the United States, and looks back with particular nostalgia on the lecture tour that secured his modest reputation in America. An early draft of the story in the Brennan Papers at the University of Delaware reveal that the story was initially entitled “The Mocker in the Corner,”[41] and so, from the start, this Irish writer is presented as a fraud. Lace is shown to be a self-aggrandizing, hard-drinking cliché and an enthusiastic generator and defender of his own celebrity status. It is against such bombastic mythmaking and self-aggrandizing ambition that privacy—and, to a point, obscurity—for the Irish woman writer takes on a new value as both a strategy of self-defense and a means of escaping the sensationalist excesses of a clichéd version of the Irish writer abroad. Such exhibitionist antics are not limited to the Irish writer in Brennan’s work. Theater critic Charles Runyon emerges in Brennan’s Herbert’s Retreat stories as an American answer to Vincent Lace’s distinctively Irish brand of literary fraud. He is repeatedly ridiculed in the stories for his self-aggrandizing tactics and jostling for position on the New York literary scene. The extent of his solipsism and craving for public recognition is revealed in the contents of his library: “His bookcase contained twelve copies of each of his own six books, the latest of which was ten years old, and on the lowest, deepest shelf he kept issues of magazines and newspapers in which articles by him had appeared.”[42]

Brennan’s exposure to different versions of visibility and celebrity through the ubiquity of publicly profiled women at work during the war years and the recasting of Hollywood stars as instructional role models as well as objects of glamorous fascination, in addition to her own early encounter with magazine celebrity in Life Magazine in 1945, meant that it became a subject of special concern in the investigations of the Long-Winded Lady. It also offered a vehicle for Brennan to consider more closely the risks that attended the public life of the woman writer at mid-century.

Brennan’s final word on the matter on the matter of privacy versus publicity, obscurity versus celebrity, appeared in a series of reflections on her writing life and creative process in the previously mentioned interview published in Time magazine in 1974. When asked about her writing life—still acutely aware as she was of the hazards that attend public visibility, especially where a vocation like writing or acting puts you at risk of seeming to entertain “notions” about your place in the world—she confessed, in a moment in which she might have been speaking on behalf of generations of Irish women writers, that she “began secretly writing a journal and poems as a girl in convent school. ‘But,’ she adds darkly, ‘the nuns found them.’” When pressed for advice for aspiring writers, Brennan’s reply is tellingly cautious and conspiratorial: “The fewer writers you know the better, and if you’re working on anything, don’t tell them.”[43]

Foundational research for this article was made possible by a Fulbright Scholarship in the Humanities (September 2012-January 2013), and I am most grateful to the Fulbright Commission and to my host institution, Fordham University in New York.

I would also like to thank the New York Public Library for access to relevant issues of “Harper’s Bazaar,” “Life” magazine, and “Time” magazine.

[1] E.B. White, Here is New York (New York: The Little Bookroom, 1999), 19.

[2] Angela Bourke, Maeve Brennan: Homesick at The New Yorker (New York: Counterpoint, 2004), 164.

[3] For detailed analysis of these stories, see Angela Bourke’s chapter “A View from the Kitchen” in Homesick at The New Yorker, Abigail Palko’s readings of key Herbert’s Retreat stories, “Out of Home in the Kitchen: Maeve Brennan’s Herbert’s Retreat Stories,” New Hibernia Review 11.4, 2007: 73-91, which includes a detailed account of the publishing history and reception of this work; and my own discussion of the these stories in the context of the history of the “Irish Bridget” in the United States, McWilliams, “Avenging ‘Bridget’: Irish Domestic Servants and Middle Class America in the Short Stories of Maeve Brennan,” Irish Studies Review 21.1, 2013: 99-113.

[4] Maeve Brennan, “The Clever One,” in The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 1998), 60.

[5] Constitution of Ireland (Dublin: Government Publications Office, 1937)

[6] Francis Sill Wickware, “Lauren Bacall,” Life, May 7, 1945, 108.

[7] Note from the Editor, Harper’s Bazaar, October 1942.

[8] Simone de Beauvoir, “Jean-Paul Sartre: Strictly Personal—A Profile of the Most Talked-About Writer in France Today,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1946, 113, 158-60.

[9] “Shopping Sleuth: Maeve Brennan Hunts Novelties and Reports them in Fashion Magazine,” Life, May 1945, 119.

[10] Ibid., 83

[11] Ibid., 32-37

[12] Bourke, Maeve Brennan, 160.

[13] Catherine Johnson, ed. The Luminous Years: Portraits at Mid-Century by Karl Bissinger (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2003).

[14] Harper’s Bazaar, January 1943, 21.

[15] “Be Yourself,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1943, 23.

[16] “The Old Glamour Girl,” Harper’s Bazaar, April 1943, 35.

[17] Ibid., 36.

[18] “The Women Who Serve,” Harper’s Bazaar, July 1943, 52-53.

[19] “The Best Dressed Women in the World,” Harper’s Bazaar, July 1943, 21.

[20] “The Woman Who Lost Her Head,” Harper’s Bazaar, September 1943, 89.

[21] Advertisement for Pond’s Cold Cream, “Anne Nissen, Gallant Bride-to-be of a Solider,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 1943, 73.

[22] Advertisement for Cutex, Harper’s Bazaar, February 1943, 53.

[23] Advertisement for Chanel Cosmetics, Harper’s Bazaar, February 1943, 93.

[24] Maeve Brennan, “They Often Said I Miss You,” Harper’s Bazaar, June 1943, 44.

[25] Dorothy Hay Thompson, “The New Spirit,” Harper’s Bazaar, April 1946, 123.

[26] Ben Yagoda, The New Yorker and the World It Made (New York: Da Capo, 2000), 43.

[27] Maeve Brennan, “Balzac’s Favorite Food,” in The Long-Winded Lady: Notes from The New Yorker (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 1997), 18.

[28] Thomas Harris, “The Building of Popular Images: Grace Kelly and Marilyn Monroe,” in Stardom: Industry of Desire, ed. Christine Gledhill (London: Routledge, 1991), 42.

[29] Maeve Brennan, “The View Chez Paul,” in The Long-Winded Lady, 165.

[30] Ibid., 169.

[31] Maeve Brennan, “Movie Stars at Large,” in The Long-Winded Lady, 107.

[32] Ibid., 108.

[33] Ibid., 110.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid., 110-111.

[36] Ibid., 112.

[37] Maeve Brennan, “A Shoe Story,” in The Long-Winded Lady, 28.

[38] “Enterprise in Old Erin: The Irish are making a Stylish Entrance into the World of Fashion,” Life, August 1953, 44-50.

[39] Helen Rogan, “Moments of Recognition: Review of Christmas Eve—13 Stories,” Time, July 1974. 62.

[40] Maeve Brennan, “The Joker,” in The Rose Garden: Short Stories (Washington: Counterpoint, 2000), 52-69.

[41] Maeve Brennan, “The Mocker in the Corner,” MS243, Box 5, Folder 30, Maeve Brennan Papers, University of Delaware.

[42] Maeve Brennan, “The Gentleman in the Pink-and-White Striped Shirt,” in The Rose Garden, 39-40.

[43] Rogan, “Moments of Recognition,” 62.