Caitríona O'Reilly. Geis. Winston-Salem: Wake Forest UP, 2015, 67 pp.

Caitríona O'Reilly's poems are essentially Irish and female, and yet they are completely her own. In her newest book, Geis, she mines the depths of myths, biology, religion, literature, art, birth, and sexuality with a deft touch and clear vision. In the hands of another poet, the density of often obscure references—to poisonous mushrooms, Aztec goddesses, and early Netherlandish paintings—could be ponderous. Instead, she nimbly uses her varied knowledge and interests to construct poems that are both densely crafted and lyrically agile. Her poems are light as air on reading, but she reminds us that “It takes the strength of sixteen horses / to part a pair of bronze hemispheres / with nothing between them” (13). Like air, her poems exert an enormous pressure and power.

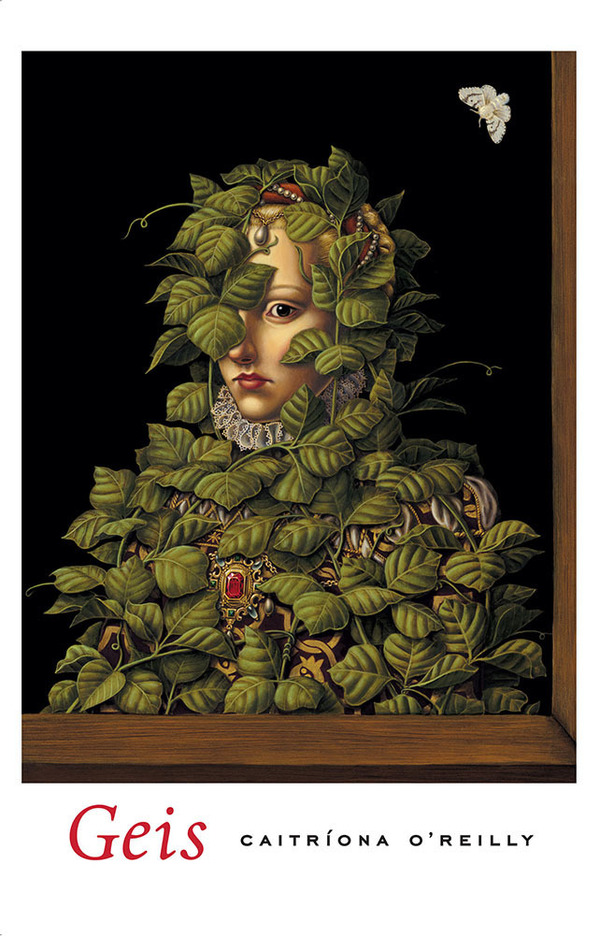

The title of the book, Geis, is an Irish Gaelic word meaning taboo. If the main goal of the cover art is to somehow illustrate the title or subtly convey a sense of the book's oeuvre, then Geis’s cover fulfills that goal, and more. It is a visual manifesto for the book, a bold assertion that functions as a kind of introduction to the poems that follow. The cover is a contemporary piece, Invasive Species II, by Madeline von Foerster, in the style of Early Modern portraiture, of a European woman—but this finely done portrait of wealthy, distinguished femininity is masked by a parasitical vine. Only half of the woman’s face is visible, and it blazes against the dark background with an uncanny gaze. The effect is unsettling and even repulsive. The cover art—of a woman being trapped, suffocated, paralyzed—does much to prepare us to read Geis. This is a book about women and women’s bodies, about being a woman in a world that continually threatens to make invisible and consume the female body. The very first poem of the collection, “Ovum,” dives into the paradox of female sexuality: the egg, with its life-giving power and possibility, yet also its passivity. The speaker begins,

You’d take it for zero, or nothing,

or the spotless oval your lips make saying it. (1)

The poem arcs over other "o" words (ocarina, oblation, obol) and considers the “phallic and obvious . . . / double o of spermatozoon” which "enters by its own locomotion—/ the flagellum, its tiny whip and scourge" (1). Along with von Foerster’s work, this poem highlights the invasive violence—physical, political, and social—enacted on women’s bodies.

“Ariadne” takes up a similar theme, where sex and maternity are linked to violence and entrapment. O’Reilly, like James Joyce, makes use here of the labyrinth myth; unlike Joyce’s Dedalus, however, O’Reilly’s Ariadne remains imprisoned in a labyrinth, where “end-stopped corridors / sprout like horns / and shut me in,” and where her screams are “loud as Pasiphae’s / whose bull-headed baby / tore her breast.” The threat of animalistic lust and violence lurks around every corner in this prison, as the speaker describes the heavy “. . . smell / of sex and sulphur—the atmosphere of rutting’s recent” (8). Ariadne has no Dedalus to make her wings, and there is little hope of escape from the dangerous labyrinth of the female body; she despairs,

It will take me a lifetime

to unpick this,

finding the right thread

to pull and unravel,

pull and unravel. (9)

The next poem, “Empty House,” further examines the tensions, ambivalences, and possibilities of female sexuality. The speaker declares, “I am a blank harvest /. . . a seedbed gone to seed.” The poem, evasive in its language but emotionally raw and direct, grapples with the complexity of unrealized female fertility. In the day, reason and practicality prevail with protected sex; instead of fertilization and growth, there are "sterile irrigations" with "a skin of rubber" (10). When sleep comes, though, the “traitor body” dreams of pregnancy, “death-in-life / and life-in-death” (11). This grief over an empty womb—the result of careful choice—displays the confusion of longing for something we thought we did not want, the pain of how our decisions and reasons are subverted by the unwieldy subconscious.

O’Reilly also examines mental illness, “a purple knot of violence in the head,” and the struggle of “getting the cramped brain / to release its grip” (18). While poems such as “Spanish Fly,” “Geis,” and “The Winter Suicides” foreground these struggles, the battle with nothingness is woven throughout the collection. At the center of these poems is the issue of human suffering, of how our lives are haunted by emptiness. The collection continually circles back to gaps, hunger, and hollowness.

This preoccupation with negative space extends to relationships and intimacy. In "Island," for example, the speaker sees a former lover "from the shore of [her] own island," and ponders the pain of this distance:

Brightness attracts me like a child:

the light-veined sea,

and the threads of light from the sky,

and you whom I see but cannot reach. (2)

The relationship is defined by gaps; while “a single lucent cord, / hung between us the quivering instant” (3), intimacy cannot be sustained. In addition, the immateriality of light can make the dark weightier, as in the section of "Geis" entitled "Jonah," where the speaker compares her mental illness to the mythical whale, “a darkness [that] swallowed me whole.” She continues, “Brothers, we who have gone down to the roots of the mountain / . . . are sea-changed, and see with the light behind us” (21).

Perhaps O’Reilly’s best and simplest articulation of the weight of despair appears in “Spanish Fly.” A wistful speaker remembers:

Yesterday the moon was a beehive

among the swarming constellations;

I thought, the universe is full of gods.

Today it is smashed atoms and dust. (5)

This tension between wonder and reductionism continues in “Comparative Mythography,” which opens with the speaker’s flat admission, “Each day brings less to believe” (12). The poem contrasts the richness of myths with the mechanical facts of science and proclaims, "knowledge means / not that it is true, but that it works." The speaker suggests that after all, the difference between religious myths and the scientific method is slim; both, at their core, are simply ways of making sense of the world. Science, which can only "[prove] that nothing exists," seems bare beside a belief system that invests the world with personality and meaning (13).

Amidst the constant yawn of nothingness, the poems do not accept utter nihilism; even though "to refuse is not to live” (21), O’Reilly suggests that gaps can also hold freedom. In the final poem, “Komorebi,” the speaker ponders the Japanese word for the spill of light through tree leaves, “the signs for ‘tree,’ ‘escape’ and ‘sun.’” In this poem, empty space liberates, as the light “exults, like any escapee, / . . . in radiant bands ascending the birch trunks” (63). Like the gardener of Alcatraz with his treasured plants, the poems slowly affirm “the word and the world’s beauty” (63), and how because of that “. . . life is worth holding onto, / even at its bitterest” (30).

In A Journey with Two Maps, Eavan Boland claims, "challenging an inherited tradition—extricating an identity from parts of it—is essential to poetic growth."[1] Caitríona O'Reilly fulfills Boland's challenge. She is a worthy heir to the Irish lyric poetry tradition, especially that of Irish women poets such as Boland and Medbh McGuckian, in her unflinching confrontation of sexuality, religion, and relationships. Yet her poems are not mere echoes; O'Reilly's clear, distinctive voice carves out her own well-deserved seat beside the established greats. Geis is mandatory reading not only for those interested in gender and Irish literature, but for all who profess an interest in Irish poetry.

[1] Boland, Eavan. A Journey with Two Maps: Becoming a Woman Poet. New York: W.W. Norton

and Co., 2011, 56.