“I was always amazed by how much light that green window let in.”

In[1] Philip Coleman and Maria Johnston’s 2011 foundational collection Reading Pearse Hutchinson: From Findrum to Fisterra, Moynagh Sullivan argues that “in placing Hutchinson we must attend to where and how he loves.”[2] The where and the how matter, according to Sullivan, because even though Hutchinson “makes the case for love as a shifter of paradigms more powerful than creed or credo,”[3] his work is marked at the same time by forms of indirection and evasion about physical love and a “discretion about sexual pleasure.”[4] In this essay, I want to extend her argument about the where and how by making more explicit what often feels implicit in Hutchinson’s work and in commentary about his work: same-sex sexuality. As Ireland more fully and openly embraces lesbian and gay citizens, as the newly opened archive of Pearse Hutchinson papers at Maynooth University brings a wealth of previously unpublished and unavailable materials to light, and perhaps as well, as we reassess Hutchinson’s poetry after the posthumous publication of Listening to Bach (2014)—a book more explicit, more joyful, and more open in its representations of homosexuality—it seems an opportune moment to queer the lens by which we have always seen and perhaps not seen Hutchinson’s poetry, to see his work in a new light.[5]

I’m thinking of Hutchinson’s delightful prose poem “Green Window,” from Listening to Bach. In that poem he describes a bare attic flat, a large bed taking up most of the space, and one small window “entirely covered—and very neatly too—by some very thin green material.”[6] He asks his companion to show him how to tie a Windsor knot. “And he did.” Hutchinson writes, “But not around my neck.”[7] In this last line, Hutchinson invites the reader to participate in a bawdy joke, to imagine where on the body the tie was tied. We do not think: on the bedpost, on my arm. No, the very act of negation that directs us away from convention (my neck) asks us to imagine the sexual implications of the context—that room filled with filtered light—and to recognize the sexual content of the poem. Indeed, this last line recasts, eroticizes, the entire poem, and suddenly what has not been seen is seen. Seeing and not seeing are central to the book. Noting another poem in which Hutchinson’s mother encounters a young male lover at the breakfast table (“What a Young Man Said to My Mother”), one reviewer remarked that the book is filled with examples of “the older generation’s way of seeing and not seeing what is before their eyes.”[8] Hutchinson writes, “I was always amazed by how much light that green window let in.” Though it is London, specifically Chelsea, light that enters the room, one almost wants to suggest that this is sexual light (the connection of the sexual to sunlight is a familiar one in Hutchinson’s work), and we like Hutchinson may be surprised by how much light that green (Irish?) screen lets in. [9]

Making sexuality—or more specifically homosexuality—more explicit allows us to ask how same-sex sexuality informs and inflects both his poetics and his politics; how forms of connection and belonging are motivated by erotic desire or identification; how the erotic modulates, impels, or subtends both Hutchinson’s insistent anti-racist and anti-partisan politics and his transnational poetry—that is, how sexuality reorients a constellation of issues that are simultaneously representational and political. An attention to sexuality may bring into focus Hutchinson’s attention to violence against gay men as a particular (and specifically Irish) form of violence among the many forms of cultural and historical violence in his work. It may also inflect our understanding of borders and border crossing as a fundamental trope of his transcultural poetics.

The 2011 Coleman and Johnston collection makes clear Hutchinson’s importance as perhaps one of the most transnational of contemporary Irish poets,[10] and in 2009 Coleman noted that Hutchinson’s work exemplifies Jahan Ramazani’s “poetic transnationalism,” which “imagine[s] a world in which cultural boundaries are fluid, transient, and permeable.”[11] Citing Coleman, Sullivan argues, “It is the centrality of love itself that configures the transnationalism of [Hutchinson’s] work.”[12] Yes, but love for whom, by whom? As I have argued elsewhere, sexuality should be an essential category for a transnational literary criticism, since Irish gay writing, especially before decriminalization in 1993, is almost inevitably transcultural in reference and transnational in scope, as queer forms of identity and belonging in Irish culture often rely on cross-cultural influences. Sexuality is a critical lens for understanding national identification or disaffiliation, thickening our sense of the cultural specificities, social materialities, and legal exigencies of national and sexual identifications.[13] Moreover, queer forms of identity and belonging intensify what Ramazani calls the affiliative and disaffiliative energies of transnational poetry. So yes, love configures the transnational, but we must attend to where and how.

~

Responding to a question about the presence of the autobiographical in his work, Hutchinson himself admitted, “I have always hovered or kind of wavered between directness and obliquity.”[14] Critics confirm this tendency, especially around representations of sexuality. As Sullivan notes, “The complexities of sexual love are modestly but compellingly explored through euphemism, punning, and associative echoes.”[15] Coleman notes a resistance to heteronormativity in Hutchinson’s work, but he also insists, when he turns to homoerotic poems, that Hutchinson “transcends” the merely physical or political or “purely ideological”—thus using the lever of transcendence to dislodge homoerotic friendship from too close or too long an association with the homosexual.[16] The risk of such an insistent critical reading is the elision of actual gay experience; that is, if homosexuality is persistently read as trope or marker of some universalized human condition, then the actual experience of the homosexual is elided or dismissed, the specificity and indeed power of the sexual evacuated from the universal and the human.[17]

What is implicit in the poetry is explicit in the archive, and what is oblique is often direct—not just because of the inclusion of deeply moving personal correspondence and love poems, but also in poems marked by a surprising openness about sexual relationships and communities. In the archive we find a directness of sexual language, poems that suggest an awareness of the sexual geographies of urban Dublin (particularly the eroticization of buses, public toilets, and theaters), the sexual practices of Irish men abroad, and a keen awareness of social attitudes towards and condemnations of gay men. In one unpublished poem, “handsome faces, furtive” eye each other in the reflection of a bus window, while the speaker watches the conductor, who is “taking the stairs like a princess in a film.”[18] More direct, if also deformed by heternormative politics of reproduction, Hutchinson writes in one unpublished love poem, “If love could start between us, anus-riding | would sow a child.”[19] One typescript poem describes how “the mind erects” on the top deck of the bus, when, “Today, example, looking down, | I saw a medical student, colored brown.”[20] Another emphatic theme in the archives is Hutchinson’s sexual attraction to men of color—one of his first major loves was Bert Achong, a Trinidadian.

Anti-racism is an important theme that surfaces in published poems about interracial children and the use of racial epithets, but it repeatedly appears in the archive in prose and poetry about interracial relationships, both straight and gay. If Hutchinson’s love for Bert Achong—memorialized in the poem “All Four Letters of It” in Listening to Bach[21]—suggests that sexual desire may inflect if not compel the anti-racist politics of the published work, the archives also suggest a caution, an attention to complexity and intersectionality, and a hesitancy about false equivalencies or easy analogies. In “Melting Pot,” Hutchinson writes: “The blackest negro I ever knew | raged against me – both drunk – | ‘You can’t begin to know or understand our hurt,’” to which the poet replies, “‘I’m queer, and wear a beard.’”[22] The poem goes on to reject the oppression Olympics suggested here and to insist on the intransigent difference and yet the invaluable alliance of race or ethnicity and sexuality.

~

Before the publication of Listening to Bach, “Two Young Men” was perhaps the most explicit poem about same-sex love of all of Hutchinson’s poems. In some ways, its explicitness about a gay relationship is undermined by its narrative, since the tale of doomed across-the-border romance in Northern Ireland is detached from the exigencies of either Hutchinson’s experience or the urban geographies he explored, and since a poem about death as a result of religious bigotry and political violence seems of a piece with so many other poems about bigotry and political violence in Hutchinson’s work. At the same time, the poem seems saturated with personal affect by its placement in Collected Poems (2002). Originally published in Poetry Ireland Review in 2001, “Two Young Men” appears in Collected Poems (2002), immediately following the poems “For Alan” and “Ten Months Later,” as if those poems marking the loss of Hutchinson’s longtime companion, Alan Biddle, in 1994, are echoed somehow in this narrative of a young man’s loss of his lover.

Over the course of the poem’s three stanzas, two young men in Belfast, one Protestant, the other Catholic, fall in love, exchange tokens of that love, and one loses the other in an act of political violence.[23] Hutchinson writes:

Two young men in Belfast fell in love,

hands reaching out in real peace

across the dangerous peace-line.

The gave each other pleasure –

maybe even happiness, who knows? –

and one day the protestant lad

gave his catholic lover

a plant for his window-sill,

a warm geranium.

In perhaps the only extended reading of the poem, Andrew Goodspeed focuses on the contrast of brutality and love, marked by the contrast between “real peace” and “the dangerous peace-line” or sectarian border that divides the city. “This love is the real peace process in Belfast,” he writes, “…the ‘real peace’ comes from those who make human connections across that line.”[24] The “hands reaching out” also suggest Moynagh Sullivan’s focus on “the overwhelming importance touch assumes in the poet’s aesthetic,” supported by repeated images of hands—“hands, open palms, fingers, and sometimes balled fists.”[25] I note further that these “hands reaching out” emphasize the poem’s repetitive movements across, of back and forth: across the line in the first stanza and across the city in the second, a flower given to one, pleasure given to both. That is, the poem seems to be in constant movement across lines, across borders. Even that token of their love, the “warm geranium” which the “the protestant lad | gave his catholic lover,” is placed on a window-sill, a liminal place, a threshold of the home over which winds, gazes, light cross.

Further, sounds echo across the poem, not just the repetition of “across” in the first two stanzas, but also the horrifying rhyme of sill and kill—as violence enters the poem in the second stanza:

Then the catholic street was torched,

and the catholic boy killed.

His lover ran both gauntlets

across the god-fearing city

and rescued back, against the odds,

that plant of trust,

his flower of love.[26]

The words god and odds are linked by internal rhyme in the second stanza as well—as if “against the odds” includes a resistance to the religious strictures of “the god-fearing city.” In the final stanza, a couplet, the “real peace” of the poem’s second line finds an ironic rhyme: “That flower was all his own now, | his loss replete.” The uneasy rhyme of peace at the outset with a loss replete at the end suggests that the ultimate peace is death (as in rest in peace). This rhyme is furthered by the alliterative chain across the poem that leads us through the l-sounds of love-line-lad-lover-love-loss. As these movements settle into the last stanza, we may also notice further transformations that enforce the poem’s intent: the almost reversal of sounds in was-all-his and his-loss, and the anagrammatic conjunction of own-now (now a wicked slant rhyme off who knows?—as if to suggest that now we do).

The lovely and close concatenation of sounds in “warm geranium”[27] seems to emphasize their closeness, though the poem gradually marks even its transformation through sound, as the euphonious pair is transformed into greater abstraction (plant of trust, flower of love), and finally the flat deictic “that flower.” Perhaps the most horrifying word in the poem is one that seems to have no real alliterative or assonantal echoes: “rescued.” Horrifying because his rescue of the token, now a fetish of loss, only emphasizes his inability to “rescue” his love, which is what he knows now. The use of figure here—that ambivalent flower—is both condensation and displacement (of the erotic). It is a figure that metaphorically replaces a narrative, a fetish that metonymically replaces a loss. As a beautiful thing marked by loss, the flower echoes the music the poet’s dead love listened to in “Ten Months Later,” which precedes “Two Young Men” in the Collected Poems—music that “arrives on the radio, | music he loved.” The speaker admits, “I used to love it too,” but adds, “How can I enjoy it now,” marked as it is by the lover’s loss.[28]

Finally, I would note that the poem itself is transnational in composition and impulse. The title is perhaps taken from a poetic translation Hutchinson wrote of Catalan poet Josep Carner, a static scene of two young men at a window talking about their disenchantment, titled “Two Young Men.”[29] Also, I can’t help but hear “We two boys together clinging,” especially given Walt Whitman’s influence on Hutchinson, noted by critics and Hutchinson himself,[30] and given the charged lines from Whitman’s own poem, “One the other never leaving, | Up and down the roads going—North and South excursions making.” Further, the poem surely suggests Frank McGuinness’s 1994 poem “Hanover Place, July Eleventh,” which features a comparable gay romance in the North, emphatically a poem of borders—though in McGuinness’s poem it isn’t peace walls that divide the city but the river that divides the Protestant city from the Catholic estates.

Though Hutchinson’s poem insists on movement across borders, the movement of the McGuinness poem is predominantly one of contraction and retreat, space constricting from the town and river to the Georgian house (a “refuge of books and papers”) to the lovers’ bed. “Aliens at home, this is where we live,” McGuinness writes, “Ireland and England with no right to love.”[31] National borders inflect the relationship, to the extent that each man seems synecdoche of his nation and both men are marginalized by and within the nation. The slant rhyme of live/love foregrounds the incompatibility of nation (“where we live”) and sexuality (“no right to love”). The poem first appeared in 1980 in the literary magazine Cyphers (which Hutchinson cofounded)—the year before the Dudgeon decision in the North, which legalized homosexuality there. The poem concludes McGuinness’s first collection of poetry, Booterstown, which appeared in 1994, the year of Alan Biddle’s death, the year after male homosexuality was decriminalized in the Republic, and the year before Hutchinson’s Barnsley Main Seam. The 1980 publication may suggest McGuinness’s poem as a source for the phrase “right to love,” which Hutchinson would use as title for a poem about a heterosexual Irish-British romance in Barnsley Main Seam, though the phrase may have been a common one at the time, given the Jeff Dudgeon sodomy law case and the subsequent David Norris case in the Republic. Still, even though Hutchinson would use the phrase in 1994 in a poem about a socially prohibited heterosexual romance, the use in McGuinness suggests the phrase is also charged with the legal criminalization of homosexuality.[32]

~

In another poem from the Hutchinson archive, the poet writes of two men kissing: “You saw the two men kissing in the lounge,” in order to “make it known | that certain popular laws have their disdain.” [33] The poem emphasizes the alcohol-fueled bravado in the pub but also their lack of bravery elsewhere—reminding us that Hutchinson was of a different generation, criminalized under law and stigmatized by church, and unable to live openly in the ways that later generations would insist upon. Indeed, as he wrote in the introduction to The Soul That Kissed the Body, he had to leave Ireland—“not just home but homeland”—in order to find autonomy and freedom, to give “joy full rein.”[34] But the poem also suggests a pervasive sense of threat or violence, emphasized by the address to a heterosexual observer and by the comparison of the men to roaches: “And so perhaps you thought them simply show-offs, | pansies pushing their own peculiar lust | before the boredom or the bored disgust, | of one who couldn’t care less if they coupled with roaches.”[35]

The comparison of gay men to roaches is a statement of social status: they are vermin, dehumanized, other, to be abused, exterminated. On September 10, 1982, a gang of young men beat another young man, Declan Flynn, to death as part of their campaign, as they said, to clear Dublin’s Fairview Park of gays. All five young men received suspended sentences. These events prompted public outrage and a protest march (the “Stop Violence Against Gays and Women” march of March 19, 1983), but the crime and its legal aftermath also made visible the potential and actual effects of homophobic discourse on queer peoples, and a tacit legal approval of the violence.[36] Hutchinson returned to this moment again and again in his published and unpublished work, shifting his focus with each poem but also linking homophobia to other forms of sexual stigma—specifically the death two years later (1984) of Ann Lovett while giving birth in a grotto in Granard, and the emblematic image (also used by Seamus Heaney) of an Irish girl tortured for “walking out” with a British soldier in the North. One of the earliest poems seems to be “Remember in the forties growing up,” a two-page typescript in the archives, in which he is already connecting Lovett and Flynn, but also commenting on the larger cultural context of girls “taking the boat” (to obtain abortions in England), and the “screamers” and “raving queens” in the bars “long before the word gay was invented.”[37]

After this, a series of published poems start to tighten the focus on Lovett and Flynn. In “The Lie of Fear” from The Soul That Kissed the Body (1990), Hutchinson attacks the “lies in the tribe’s code,” lies about sexuality and stigma that result in “a girl who died in a field, | her child who died beside her, | a young man who died in a park”—“he got beaten to death because | they thought he liked men more than women” (90-93). In Barnsley Main Seam (1995), Hutchinson returns to the theme in “Let’s Hope,” but makes it last in a sequence of three poems assessing the murderous effects of cultural stigma. The first, “The Right to Love,” focuses on a young woman tarred and feathered for “walking | with a British Tommy,” a theme familiar from Seamus Heaney’s “Punishment.”[38] The second poem, “She Fell Asleep in the Sun,” attempts to reverse the stigma of illegitimacy by emphasizing folk language about unwed births as the result of a girl lying too long under the sun. In “Let’s Hope,” Hutchinson returns to Lovett and Flynn, juxtaposing them almost line by line rather than stanza by stanza as he had in “The Lie of Fear.” He names Lovett, but still does not name Flynn, naming instead the park, Fairview Park, where he was beaten to death. The poem is tighter, succinct, almost paratactic:

A girl and her child

extinct in a field.

A boy got beaten to death in a park.

They didn’t mean to kill him.

They live.

His family said he wasn’t.

Nobody meant to kill her.[39]

The use of the word “kill” for Lovett renders religious bigotry and cultural violence as equally murderous to gay-bashing.

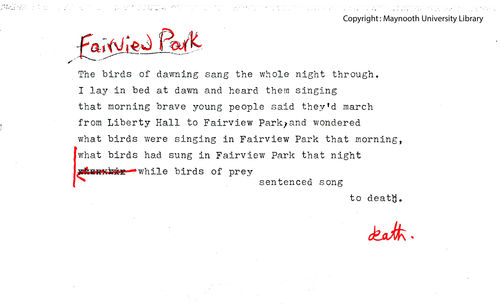

Though this is the last word in the published verse, it is not Hutchinson’s last turn at the Fairview Park story. A late unpublished poem drops Lovett and turns to what happened after the murder of Flynn: the 1983 March Against Violence, using the pastoral trope of birdsong to connect one moment to the other:

FAIRVIEW PARK

The birds of dawning sang the whole night through.

I lay in bed at dawn and heard them singing

that morning brave young people said they’d march

from Liberty Hall to Fairview Park, and wondered

what birds were singing in Fairview Park that morning,

what birds had sung in Fairview Park that night

while birds of prey

sentenced song

to death.[40]

~

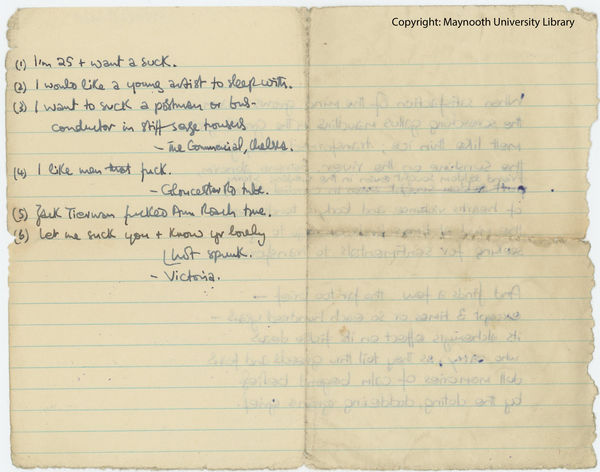

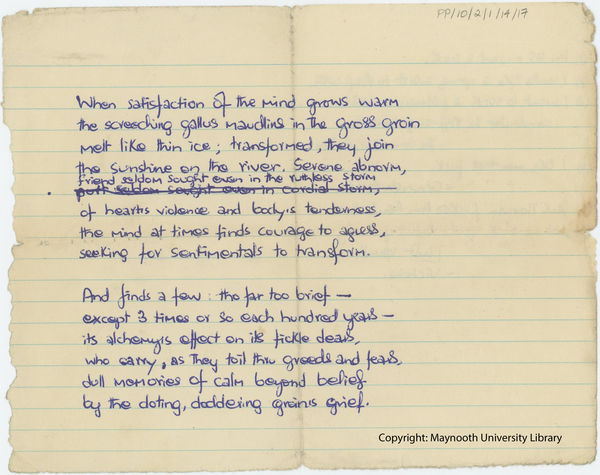

By way of conclusion, let me turn to a late poem from the archives, “Deathless Cries,” a poem that, for me, suggests that we resist interpretive tropes of transcendence and insist instead on Hutchinson’s own work of transformation. If some of the early and unpublished texts suggests an awareness of sexual geographies and the practices of urban sexual cruising, other scraps and marginalia in the archive indicate an almost documentary curiosity about sexual subcultures and sexual practice. The back of one short poem offers a careful listing (with numbers and locations) of bathroom graffiti in London:

- I’m 25 & want a suck.

- I would like a young artist to sleep with.

- I want to suck a postman or a bus-conductor in stiff sage trousers.

- The Commercial, Chelsea

- I like men that fuck.

- Gloucester tube

- Jack Tierney fucked Ann Roach true.

- Let me suck you & know yr lovely hot spunk.

- Victoria[41]

Sexual graffiti, but also references to public sex, known in Ireland and the UK by the euphemism “cottaging”—a sexual subculture that should be familiar to any who has read Cathal Ó Searcaigh’s London migrant poems. In Ireland and elsewhere, cottaging established a counter-public queer space of identification and belonging that the dominant culture would condemn or disavow.[42]

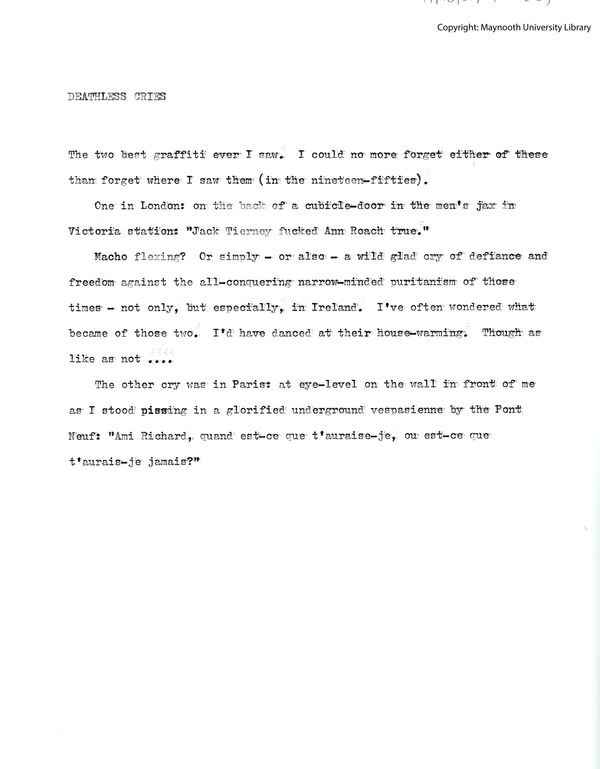

I was surprised to find, in a folder marked “New Poems” (contemporary with those collected in Listening to Bach), a poem called “Exultation,” which repeated, word for word, the bathroom graffiti about Jack Tierney and Ann Roach. Behind that poem, another called “Nightwood” (an echo of Djuna Barnes) in which he recounts a homoerotic scrawl written above a Parisian urinal. And finally, a poem called “Deathless Cries,” in which he combined these two texts:

The two best graffiti I ever saw. I could no more forget either of these than forget where I saw them (in the nineteen-fifties).

One in London: on the back of a cubicle-door in the men’s jax in Victoria Station: “Jack Tierney fucked Ann Roach true.”

Macho flexing? Or simply—or also—a wild glad cry of defiance and freedom against the all-conquering narrow-minded Puritanism of those times—not only, but especially, in Ireland. I’ve often wondered what became of those two. I’d have danced at their house-warming. Though as like as not….

The other cry was in Paris: at eye-level on the wall in front of me as I stood pissing in a glorified underground vespasienne by the Pont Neuf. “Ami Richard, quand est-ce que t’auraise-je, ou est-ce que t’aurais-je jamais?” [43]

He could “no more forget” them, of course, because he had written them down, but what is fascinating here is the way he has transformed that material. One notation he wants to imagine led to a household, though he admits “like as not,” not. The other, the queer one, he finds in a public urinal, where he reads, “Richard, my friend, when will I have you, or will I ever have you?” That the ambiguous word ami-friend is written on a urinal locates it in homosocial space—a charged example to add to Coleman’s analysis of the ambiguous figure of friend-as-lover, one that would resist, I think, transcendent reading. The language remains French, as if to make clear that sexual boundary crossing is of a piece with linguistic and cultural boundary crossing, but it is also an appeal for another time—a when. If Sullivan reminds us to be attentive to the where and how of love in Hutchinson’s poetry, this poem suggests we also pay attention to the when, a displaced future, a queer time and place in which one might finally have the right to love.

Finding that documentary scrap in the archive early in my research confirmed that I would find a richer queer cultural context for understanding Hutchinson’s poetry, but finding that late poem “Deathless Cries” indicates that among the minority cultures and languages and voices Hutchinson brings to us are the subterranean, dismissed, and disavowed languages of a queer culture. That we should add to the list of minority cultures we bring to study his work that of queerness. That we should go back to the green window, and maybe find ourselves amazed at how much light that green window may let in.

[1] All images in this article used with permission by the Maynooth University Library.

[2] Moynagh Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details’: Love, Sex, and Embodiment in the Poetry of Pearse Hutchinson” in Reading Pearse Hutchinson: From Findrum to Fisterra, eds. Philip Coleman and Maria Johnston (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2011), 75.

[3] Ibid., 73

[4] Ibid., 80.

[5] I would like to thank Cathal McCauley and the Maynooth University Library for a bursary which allowed me to pursue extended research in the Pearse Hutchinson archive. I express my deepest thanks to archivist Ciara Joyce for her invaluable guidance and assistance, and to Moynagh Sullivan for her encouragement in this work. I would also note my gratitude for Philip Coleman and Maria Johnston’s collection, Reading Pearse Hutchinson: From Findrum to Fisterra, and my debt, especially, to the essays by Coleman (on friendship), Andrew Goodspeed (on violence and bigotry), and Sullivan (on sexuality and the body).

[6] Pearse Hutchinson, “Green Window,” Listening to Bach (Oldcastle, County Meath: Gallery Press, 1990), 37.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Belinda Cooke, in The North, review cited on the Gallery Press website, accessed May 1, 2016, http://www.gallerypress.com/store/#!/~/product/id=34606919.

[9] See Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details,’” 78-79.

[10] Philip Coleman and Maria Johnston, “Introduction” to Reading Pearse Hutchinson: From Findrum to Fisterra, ed. Philip Coleman and Maria Johnson (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2011), 8. “From the start,” Coleman and Johnston note in their introduction, Hutchinson has “moved between nations, cultures, and languages,” his poems offering “a space of cultural openness and conjunction”; ibid., 10.

[11] See Philip Coleman, “At Ease with Elsewhere,” review of Collected Poems and At Least for a While, by Pearse Hutchinson, Dublin Review of Books, 2009, accessed May 1, 2016, http://www.drb.ie/essays/at-easewith-elsewhere.

[12] Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details,’” 77.

[13] See Ed Madden, “Transnationalism, Sexuality, and Irish Gay Poetry: Frank McGuinness, Cathal Ó Searcaigh, Padraig Rooney” in Where Motley Is Worn: Transnational Irish Literatures, ed. Amanda Tucker and Moira Casey (Cork: Cork University Press, 2014), 83-100.

[14] Phillip Coleman, “From Findrum: Pearse Hutchinson in Conversation,” in Coleman and Johnston, Reading Pearse Hutchinson, 227.

[15] Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details,’” 78.

[16] I deeply value Coleman’s readings of the ways Hutchinson represents friendship as “both physical and metaphysical in its meaning,” but it is worth noting the insistent turn in his readings toward the “transcendent power” of friendship, and his emphasis on a complexity that “would seem to transcend a purely ideological or political reading”; see Philip Coleman “‘He donat la meva vida al amor dels amics’: Pearse Hutchison and the Poetics of Friendship” in Coleman and Johnston, Reading Pearse Hutchinson, (esp.) 67, 69, 71.

[17] In Mark Lilly’s survey of “Straight Talk” about gay and lesbian literature, he notes that in traditional criticism, “writings descriptive of heterosexual love are about heterosexual love, whereas writings descriptive of homosexual love are metaphors for something completely different”; see Mark Lily, “Introduction: Straight Talk” in Lesbian and Gay Writing: An Anthology of Critical Essays, ed. Mark Lily (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 6.

[18] From a collection of unpublished draft poetry from the 1940s and 1950s; see Pearse Hutchinson, “This evening the charming conductor,” PP/10/2/1/14/33, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, Maynooth University Library Special Collections [MULSC].

[19] Hutchinson, “If love could start between us,” PP/10/2/1/13/43, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[20] Hutchinson, “On top decks I feel the most elation,” PP/10/2/1/13/11, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[21] See Listening to Bach (28). In this haunting poem, Bert’s name is written in the snow, a suggestion of the ephemerality of human relations but also, perhaps, an ironic comment on race.

[22] From Hutchinson, “Melting Pot,” Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC; this is a typescript in a collection of uncatalogued folders of draft poetry and unpublished poetry in the archive, unprocessed at the time of this writing.

[23] Pearse Hutchinson, “Two Young Men,” in Collected Poems (Oldcastle, County Meath: Gallery Press, 2002), 278.

[24] Goodspeed adds, “That this poem appears to describe a homosexual relationship also supports this notion that Hutchinson applauds the lovers’ readiness to seek love and companionship in ways that cut across traditional social expectations”; see Andrew Goodspeed, “‘The Gentle Are More Real than the Violent’: Violence, Bigotry and Humanity in Pearse Hutchinson’s Poetry” in Coleman and Johnston, Reading Pearse Hutchinson, 50.

[25] Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details,’” 81.

[26] Hutchinson, “Two Young Men,” 278.

[27] I recall here that “warm” functions as the mark of shame for men accused of loving other men in “A True Story”; see Hutchinson, “A True Story,” Collected Poems, 119.

[28] The flower also exemplifies Hutchinson’s use of the small and ordinary to suggest more expansive meaning, claims of ethical value or images of visionary power; see Ciaran O’Driscoll, “That Small, Vast Space: minute Details and Brief Moments in the Poetry of Pearse Hutchinson” in Coleman and Johnston, Reading Pearse Hutchinson, 123.

[29] This poem does not appear in Hutchinson’s 1962 translations of Carner’s poems, nor in Done Into English: Collected Translations, though it may have been published elsewhere. I read the translation in Notebook F, PP/10/2/1/12/7, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[30] See Maria Johnson, “‘The Music of What Matters’: Music and Movement in the Poetry of Pearse Hutchinson” in Coleman and Johnston, Reading Pearse Hutchinson, 32; and see Coleman “From Findrum: Pearse Hutchinson in Conversation,” 220.

[31] Frank McGuinness, “Hanover Place, July Eleventh,” Booterstown (Oldcastle, County Meath: Gallery Press, 1994), 85.

[32] For an extended reading of the McGuinness poem, see Madden, “Transnationalism, Sexuality, and Irish Gay Poetry.”

[33] Hutchinson, “[You saw the two men kissing in the lounge],” PP10/2/1/15/25, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[34] Pearse Hutchinson, The Soul That Kissed the Body (Oldcastle, County Meath: Gallery Press, 1990), 14.

[35] Hutchinson, “[You saw the two men kissing in the lounge].”

[36] The 1983 march, the first major public demonstration for gay rights in Ireland, was later characterized by AIDS activist Ger Philpott as “Ireland’s Stonewall,” a reference to the Stonewall Riots in New York in 1969, often seen as a tipping point in the gay rights movement in the U.S.; see Ger Philpott’s “Martyr in the park” in (the short-lived Irish gay magazine) GI [Gay Ireland], no. 1, November 2001: 52-8.

[37] The typescript comes from unpublished draft poetry, PP10/2/1/16, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[38] Comparing “The Right to Love” to Seamus Heaney’s “Punishment,” Moynagh Sullivan emphasizes Hutchinson’s rejection rather than acceptance of the tribal morality—his poem enacting “a facing away from the aesthetics of national identity.” In the domain of “tribal reproduction,” she writes, “miscegenations and queer desire have no place, having the wrong and no outcome respectively”; see Sullivan, “‘No Undue Details,’” 76.

[39] Hutchinson, “Let’s Hope,” Barnsley Main Seam (Oldcastle, County Meath: Gallery Press, 1994), 15.

[40] At the time of this writing, the poem was not yet cataloged, in a collection of unprocessed draft and unpublished poetry.

[41] This list appears on the back of “When satisfaction of the mind grows warm,” PP10/2/1/14/17, Pearse Hutchinson Archive, MULSC.

[42] In the introduction to Quare Fellas, the first collection of Irish gay short fiction (1994), Brian Finnegan noted that cottaging was “a strong tradition in Ireland […] often the only guaranteed sexual outlet for gay men in rural areas and small towns to meet other men”; see Finnegan, ed., Quare Fellas: New Irish Gay Writing (Dublin: Basement Press, 1994), 9. Tim Edwards calls the public washroom or toilet “probably the most established and oldest male homosexual information institution,” because it was accessible, exclusively male, and “a legitimate means for meeting others”; see Edwards, Erotics and Politics: Gay Male Sexuality, Masculinity and Feminism (London: Routledge, 1994), 100.

[43] Hutchinson, “Deathless Cries,” from a folder of recent “New Poems” in the archive, uncatalogued at the time of this writing.