Standish O’Grady’s Cuculain: A Critical Edition. Edited by Gregory Castle and Patrick Bixby. Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press, 2016, 298 pp.

Like Christy Mahon’s father in John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World, Standish O’Grady has an odd habit of turning up when least expected—and when everyone thinks he is dead. The most striking instance, perhaps, is an article published in early February 1969 in The Irish Times on the worsening situation in Northern Ireland. The article appears after a Civil Rights Association protest in Newry descended into violence, following the infamous loyalist attack on a Civil Rights march at Burntollet bridge in Derry two weeks earlier. The Irish Times column on the Newry demonstration was penned by the novelist and broadcaster Benedict Kiely, a native of County Tyrone. Kiely devotes much of his column, “An Ulster Notebook,” to reflecting on the associations of the area around Newry with the ancient tale of Cuculain and the Táin Bó Cuailgne as O’Grady had once narrated it. Wondering how O’Grady would describe the place now, with its cattle-smuggling across the border and the Troubles beginning all round, Kiely ponders that O’Grady’s elevated prose might transform “a Paisleyite bludgeon into the Gae Bolg.”[1] This refers to the sticks that loyalist supporters of Ian Paisley used in attacking the Civil Rights marchers at Burntollet and also to the name of Cuculain’s sword in O’Grady’s writings on the ancient mythical warrior of Ulster.

In Standish O’Grady’s Cuculain: A Critical Edition, editors Gregory Castle and Patrick Bixby have done a wonderful job in bringing O’Grady’s writing to life once again. There is so much to admire in this book, which should be on the shelves of those interested not just in the story of Cuculain, but in that strange cultural outpouring of the late 19th century for which we still struggle to agree on a name: the Celtic Revival, the Irish Revival, the Gaelic Revival, the Irish Literary Revival. O’Grady’s lasting legacy derives from his three-volume work, History of Ireland, published between 1878 and 1881 and reprinted in an abridged format here. Castle and Bixby have made their selections from these volumes, although it should be pointed out that, strictly speaking, there was a two-volume History of Ireland, followed by a new volume one, History of Ireland: Critical and Philosophical, published in 1881 (after which no subsequent volumes were published).

Four critical essays are included after the editorial selections from O’Grady’s History of Ireland. These essays augment the primary text by illustrating its significance in its time to the Irish Revival and discussing it critically in historiographical, gender and political terms. In Renée Fox’s chapter on O’Grady’s sources, she draws attention to Eugene O’Curry’s Lectures on the Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History (1861) as one of the main sources for O’Grady’s work. The acknowledgement is important, pointing as it does not only to the body of manuscript materials that O’Curry had compiled as a basis for the narrative of Irish mythology that O’Grady creates in History of Ireland, but also to the immense and scattered range of characters, places, and events with which O’Grady had to contend. In their illuminating essays on O’Grady’s narrative, both Fox and Joseph Valente draw attention to the omissions from original sources in History of Ireland, omissions that O’Grady made with a view to presenting Cuculain and the story of the war of the bull of Cooley in a noble, manly light, as Valente points out.

Yet when readers plunge into the narrative of History of Ireland in this critical edition, such is the range of characters and places—and so blurred are distinctions between supernatural and natural events—it would seem impossible for O’Grady to have done otherwise with his sources in his day. As a measure of the challenge that O’Grady took upon himself in writing a narrative of ancient Irish history based around the Ulster cycle of legends, it is telling that Castle and Bixby have, in a certain sense, repeated a pattern. Just as O’Grady tried to put the excess of characters and stories in the original manuscripts that O’Curry compiled into an epic narrative order, so too do Castle and Bixby tone down the persistently digressive nature of O’Grady’s narrative in order to allow readers to grasp the fundamental theme of History of Ireland. The form of digression in O’Grady’s work is consistent with the pattern in The Odyssey that Eric Auerbach identified over sixty years’ ago in Mimesis (1954). Recognizing an echo of O’Grady’s original editing process in Castle’s and Bixby’s editorial selections, the reader’s sympathy for O’Grady is deepened: appreciating how onerous the task was that he took upon himself in the 1870s. Indeed, it is a little unfair of Fox to imply a degree of opportunism on his part when she writes of O’Grady having “borrowed” much of his materials from O’Curry’s lectures (193): an antiquarian cattle-raid of sorts. Fox may be right in asserting that O’Grady had at best a superficial knowledge of the Irish language. However, there is nothing to contest the possibility that, when composing the volumes of History of Ireland, he had carried on some dialogue with his cousin, Standish Hayes O’Grady, a foremost Irish language scholar of his day and an important associate of Douglas Hyde, founder of Conradh na Gaeilge in 1893.

One of the biggest challenges that History of Ireland presents for today’s readers is the sheer variety of ancient character-names and place-names that appear in the original text, coupled with O’Grady’s spellings of these names: spellings that are often idiosyncratic. Thus, Castle and Bixby have done a great service in the glossary that they provide: one that not only gives brief explanations of names, but also variants on spellings that are used in different versions of the tales associated with Cuculain and the Táin. This is particularly valuable for marshalling the many differences in name-spelling in the poetry, drama, and fiction of the Irish Literary Revival that got underway in Dublin ten years after the publication of History of Ireland. Entries that the editors provide for such terms as “Olnemacta” are immensely useful by informing the reader that this was the name for Connacht in the time in which Cuculain was believed to have lived, as well as being the name of the tribe of warriors who fought under Queen Maeve (278). One of the most fascinating entries links Cuculain to the Isle of Skye, the largest island of the Hebrides off of the northwest coast of Scotland. Readers learn that the island takes its name from Scathach, one whom the editors describe as the “Amazonian warrioress” of Irish legend who was said to have trained Cuculain and other Ulster heroes in martial arts on the island. Scholars interested in Irish-Scottish cultural and historical connections under that shape-shifting rubric, “archipelagic studies,” would do well to take note. Having said this, when Castle and Bixby translate a phrase from a line from Tierna (11th century Abbot of Clonmacnoise), one that O’Grady quotes in opening his chapter “Boyhood of Cuculain,” they overlook the fact that the Romans and early medieval monks often used the term “Scotia” for Ireland.[2] The editors translate “fortissimus heros Scotorum” as “greatest of Scottish heroes,” a phrase that was more likely to have meant “greatest of Irish heroes” (71). The hazards of the editors’ endeavours are also revealed in their glossary entry for “Dectera.” Castle and Bixby take the name as referring to the King of South Cooley (the peninsula on the border of South County Down and North County Louth) when, more importantly, Dectera was the name of one of the sisters of the King of Ulster, Concobhar MacNessa, and the human mother of Cuculain, first named Setanta. This slip indicates not just the density of the materials in O’Grady’s writing with which Castle and Bixby have had to contend; it also points to the same kind of density that O’Grady himself tried to get some grip on when composing his History of Ireland.

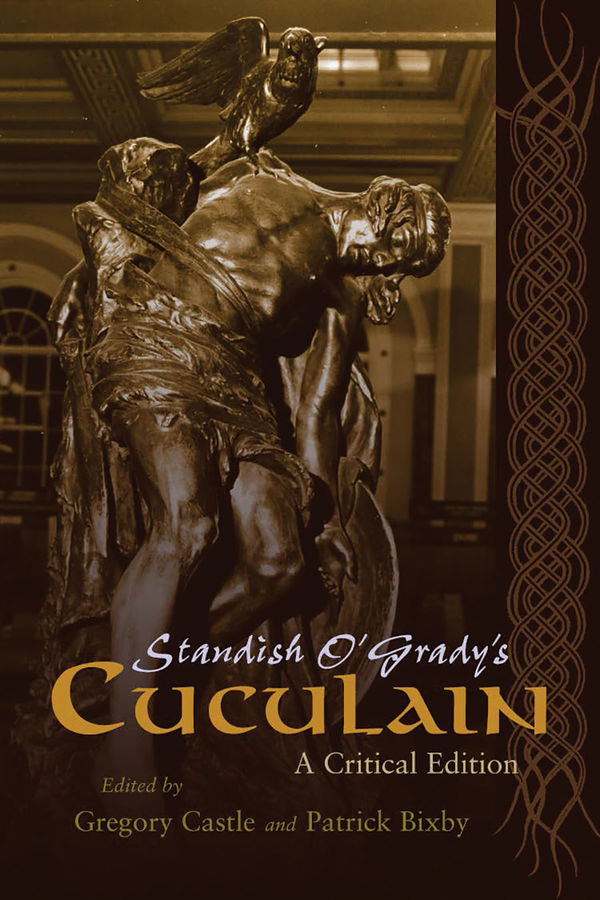

Accessible for students, scholars and general readers, Standish O’Grady’s Cuculain opens several new paths of critical evaluation for years to come, both in terms of Cuculain as a mythical icon and in terms of O’Grady’s writing more generally. Particularly in the deep fraternity that Cuculain expresses for his boyhood friend Fardia in a chapter from History of Ireland not included in this edition, the queering of Cuculain comes into consideration: the meaning that might be attributed to the hero speaking of sleeping with Fardia under the same rug after rampaging through cities, for example. Valente points in this direction when drawing a helpful distinction in his essay between hypermasculinity and manliness, observing in O’Grady’s version of Cuculain a toning down of the more outlandishly-violent and grotesque features of the tales of Cuculain in Irish medieval accounts (212). Valente’s rephrasing of David Cairns’s and Shaun Richard’s description of the Gaelic people as “an essentially feminine race” to “an essentially masculine race” is altogether too hasty however (212). In Writing Ireland (1988), Cairns and Richards were paraphrasing Matthew Arnold critically. The very excess of violent passion that Valente observantly describes as hypermasculine was actually a feature of what Arnold had identified as the feminine nature of the Celtic temperament in On the Study of Celtic Literature (1867): ferocious and hysterical, incapable of measure in emotions. Apart from this issue of the gender politics of Cuculain, there is the matter of the depth to which O’Grady fashioned the knightly image of Cuculain that arises in History of Ireland under the strong influence of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s version of the legend of King Arthur in Idylls of the King. Castle’s and Bixby’s edition calls for greater exploration of the English, Scottish, and Welsh mythical and literary strands in O’Grady’s writing; what intertextual and international significance these hold for the idea of Cuculain as a monument of Irish destiny, and most especially, a Northern Irish destiny. This, of course, raises the question of history itself. Castle’s and Bixby’s opening selections from History of Ireland demonstrate just how profoundly O’Grady was preoccupied with this issue: insisting that his work be regarded not in the Wordsworthian sense as a flight of imagination but rather as a narrative bringing to life the rudiments of a far-distant Irish past. In his excellent discussion of the afterlife of O’Grady’s Cuculain, particularly embodied in Oliver Sheppard’s statue of the warrior in Dublin’s G.P.O. to commemorate the 1916 Rising, Bixby points to the power of a narrative that endures to present times. In this age of cinematic versions of The Lord of the Rings and the huge popularity of Game of Thrones, perhaps Standish O’Grady’s Cuculain will prompt a new range of works—digital cinematic, dramatic, poetic—to bring O’Grady’s mythographic narrative to new generations.

[1] Benedict Kiely, “An Ulster Notebook: Who ever said the North was dour?” The Irish Times, February 7, 1969, 12.

[2] See, for example, the sixth-century monks Gildas, Isidorus Hispalensis and Capgravius, as cited in Martin McDermot, A New and Impartial History of Ireland, vol. 1 (London: McGowan, 1823) 60, 64. Peter Berresford Ellis states that in early medieval Latin, the term Scottus was applied to the Irish. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 195.