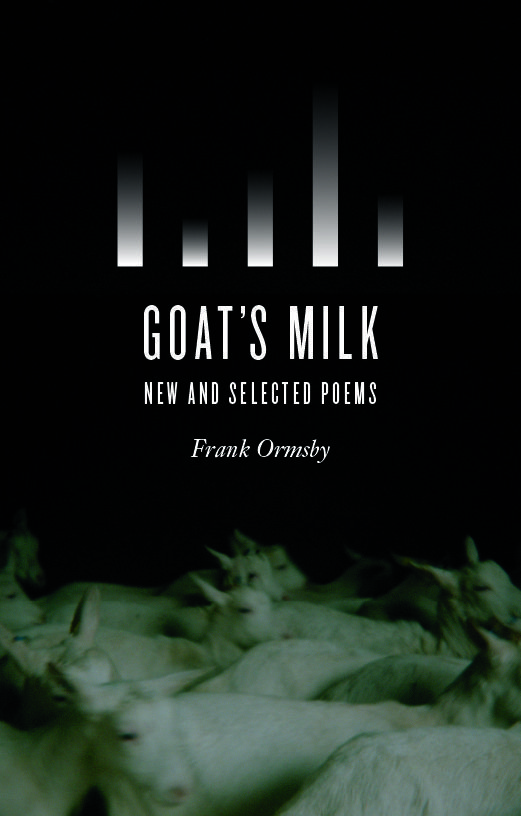

Frank Ormsby. Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems. Winston-Salem: Wake Forest University Press, 2015, 192 pp.

Assured and often understated, Goat’s Milk: New and Selected Poems brings together nearly four decades of Frank Ormsby’s poetry, selecting from his four previous collections and including forty-six new poems. This fresh synthesis further advances the concerns of Ormsby’s oeuvre in an increasingly concise, even minimalist, manner. The volume also includes a generous introduction by Michael Longley, probably the most accomplished Ulster poet working today, which explores Ormsby’s place within the recent history of Northern Irish poetry. Ormsby, who belongs to the generation of Northern Irish poets associated with names such as Medbh McGuckian, Paul Muldoon, Tom Paulin and Ciaran Carson, is the last of his set to publish a retrospective, and he has been largely overshadowed by his more innovative contemporaries; however, the publication of Goat’s Milk gives readers the opportunity to reassess the work of a significant figure, and will certainly add to his reputation outside of Northern Ireland.

Beginning with selections from Ormsby’s debut, A Store of Candles (1977), Goat’s Milk allows the reader to enter a world of haunted domestic spaces, of nuanced and somewhat evasive imagery. In the best of these poems, the desire to resolve and the reticence to dig under the surface are avoided in preference of a poetics that allows for uncertainty, for lines and images that slip from the reader just as they threaten to solidify. The poems are full of hauntings, a recurrent theme in Ormsby’s poetry, but, like ghosts, they are more affecting when they exist in uncertainty, in tricks of the light. In “Landscape with Figures,” one of the best poems in this early collection, the poem begins with the lines, “What haunts me is a farmhouse among trees / seen from a bus window” (21), and introduces the figures of a girl climbing a hill and a woman waiting. From this observed scene, where “nothing had happened” (21), Ormsby carefully unravels his poem but does not attempt to fix it to a definite ending. Instead, he writes of “the thing I saw / and could not fathom” (21), noting in the final lines,

I seem to share in sense, not detail,

what was heavy there:

sadness of dim places, obscure lives,

ends and beginnings,

such extremities. (21)

In other ways, poems such as “Wet Leaves,” “Stone,” and “In Memoriam” move elegantly and suggestively through acutely observed images, avoiding easy epiphany in favor of this “haunting” effect. It is in these poems that we see what is best in the young Ormsby, and thankfully it is from these that he begins to extrapolate and explore a host of concerns over the coming collections. More famous (and less skilful) poems, such as “Sheepman” and “My Friend Havelock Ellis,” are less mature, less confident in the ability of a poem to affect without the weight of a snarky persona and an often heavy-handed social observation.

Nearly a decade later in Ormsby’s follow-up collection, A Northern Spring (1986), Ormsby’s poetry exhibits a significant advancement, both stylistically and thematically. At the heart of this beautiful collection is a sequence of thirty-five war poems, which imagine the lives and afterlives of U.S. troops stationed in County Fermanagh (Ormsby’s native county) in the months leading up to the Normandy landings of 1944. Here, politics, place, and history are interwoven: global histories mix with regional ones, and places and borders become indistinct through Ormsby’s disturbing blend of violence and familiarity. One speaker, in “Cleo, Oklahoma,” says, “Already I belonged / to somewhere else, or nowhere, or the next / photograph” (47), giving voice to the migrating identities and forms central to these imagined lives. This sense of slippage, of elusiveness, which was the virtue of the better poems in A Store of Candles, is used to full effect, and gives a shocking power to Ormsby’s sequence because it avoids polemic, keeping the reader alive to the constant shifts of meaning and image. In the tenth poem of the sequence, “The Flamethrower,” the back-and-forth movements of meaning, which are revisited and reassigned over the eight-line form, typify the power of Ormsby’s maturing poetics:

We were all in the lap of the gods, as Smokey said,

an unpredictable, tumescent place.

You might be dandled there or due a caress

or fucked quick as lightning if your tree camouflage

wasn’t just right.

His own lightning rod never struck less than twice,

the woods in front of him a melting waste

of real and human trees. (53)

The “unpredictable” landscape is transformed, nature is adopted as human in camouflage, which is at first protective and then devastatingly violent. The key images are repeatedly revisited, questioned, recast in a new light. The recurrent use of trees and lightning plots the poem’s movement, but the reader never arrives at a secure ending or resting place: just as a new meaning accrues, it forces a reassessment, a remembering, a “haunting.”

In selections from The Ghost Train (1995), this sense of the poems being “haunted” by meaning rather than enclosing it reoccurs, but is brought back inside the remit of the poet’s personal, domestic, familial world. In the title poem, there is a historical anxiety about the numerous dead, how they can revisit and make themselves present without notice:

we cannot tell which ghosts are obsolete

or which may yet come sighing from the walls

with a glimmer of recognition

to take their place by more immediate shades (84)

The uncertainty of whether something has ended or whether it will reoccur draws us back to A Northern Spring, but announces also a return to Ormsby’s own “ghosts,” which exist alongside political and historical concerns in poems like “The Easter Ceasefire” and “Helen,” in which the private and public coalesce. The poems here are often small, restrained, but many are unsuccessful in their form, particularly the two sestinas, which are not as effective at reassigning and accumulating meanings as their less constrained counterparts.

Published after a thirteen-year wait, Ormsby’s Fireflies (2009), as seen in Goat’s Milk, locates itself in America, and deals in a much freer, more expansive style. Taking in pop culture, geographical detail and the features of cityscapes in lists that suggest Michael Longley’s signature style, these are poems that take from the tradition of American poetry as much as from the American landscape. Again, repetition is a key trope, but rather than being used to question and alter, in these newer poems, the repeated words and phrases are much more self-reflexive, even ironic, and are unafraid of drawing attention to themselves and their own place within the rhythmic and semantic structure of the work. In poems like “The Gate” and “Some Spring Moons, North Circular Road,” the repeated words reappear within other words, and become the key organizing structure of the poem. These are poems that are “precarious and assured” (140), confident in their ability to change speed, even to become static, and to repeat a word or phrase until its assigned meaning is brought severely into question.

The new poems in this book have the stylistic and thematic coherence of a further collection, and mark a different direction in Ormsby’s work that values the concise, even the minimalistic, taking small observed scenes and expanding their significance in short, declaratory poems. Common features occur that link back to previous collections, such as the lists that take over in poems like “Forty Shades of Green” and the political undertones of “Crossing the Border”; however, this is largely a return to the domestic, the local, which has become elegiac, often reverent, and which the poet hones to a series of clear, direct images. In “Bog Cotton,” for example, we have a single image in the first stanza, the significance of which is commented on by the second, becoming a deeply felt elegy:

They have the look

of being born old.

Thinning elders among the heather,

trembling in every wind.

My father turns eighty

the spring before my thirteenth birthday.

When I feed him porridge he takes his cap off. His hair,

as it has been all my life, is white, pure white. (151)

Goat’s Milk is a beautifully-produced edition and gives readers the opportunity to revisit and re-evaluate the work of an accomplished poet. The poems are concise, memorable and intelligent, and the selections highlight key themes, showing Ormsby’s advances and returns over the course of a long and assured career. This is a poetry of simplicity and quiet power, one of hauntings, rememberings and reimaginings, full of the “dislocated light” (89) of uncertainty, liminality, where images return to “some no-place” (89), where the global is absorbed into the regional, the public into the private.