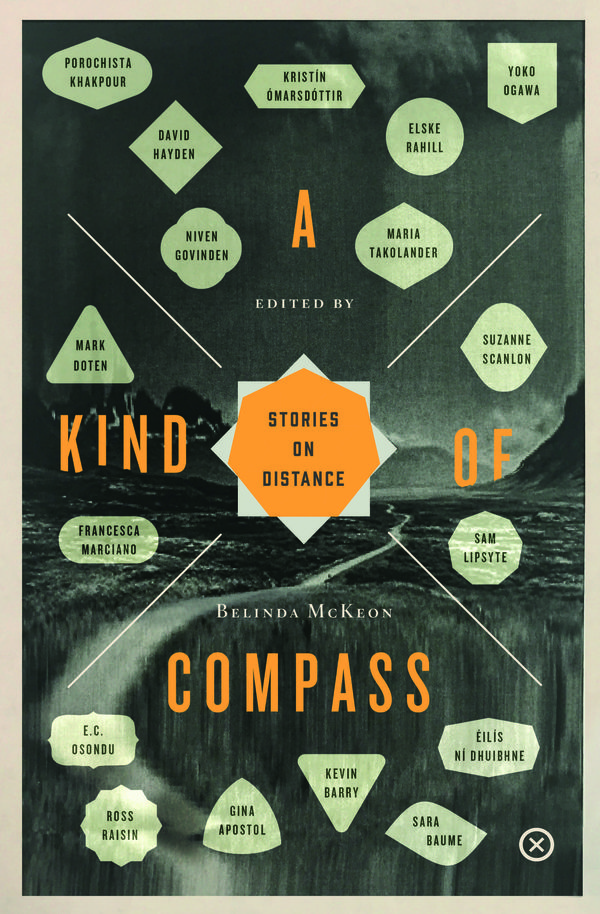

A Kind of Compass: Stories on Distance. Edited by Belinda McKeon. Dublin: Tramp Press, 2016, 246 pp.

The seventeen stories in A Kind of Compass: Stories on Distance raise the possibility that “distance,” nominally the collection’s theme, could really mean anything, or perhaps nothing at all. The selections, compiled and edited by Belinda McKeon, define “distance” from a variety of standpoints: as the miles between Earth and a woman orbiting it in a space shuttle; the emotional barrier between a middle-aged son and the dying father whose hand he holds; an almost impossible-to-imagine future in which one’s island home will be swallowed by water; and the disjuncture between televisual representations of England and its considerably grubbier lived reality. “Distance,” defined thus by various “between x and y” constructions, can be geographic, temporal, imaginative, metaphorical, or intertextual, to name just a few of the volume’s suggested possibilities. Although the collection’s theme might serve as an overly permissive unifier of its contents, the authors’ liberal interpretations of “distance” amount to an assortment of short narratives that are stronger, collectively, for their proximity to one another within the book’s pages.

In her introduction, McKeon underwrites this eclecticism by venturing a theory of the short story as being “made out of distance, out of the problem of it.” The genre’s brevity, she asserts, challenges a writer to capture “the depth of a novel, the breadth of a poem”—she quotes Amy Bloom here—within a handful of pages whose space “eats itself up greedily, like a life” (vii). To align short stories with distance seems a provocatively counter-intuitive approach to a genre often associated with spatial compression and slice-of-life abbreviation. Dickens’s biographer, Sir Frank Thomas Marzials, for example, characterized the short story as “great painting in miniature, a gem of perfect water.”[i] Like Bloom, Marzials appraises short stories for their ability to compress the heft of “great” art into a tiny frame, which to some extent tracks with McKeon’s digestive metaphor: pages eat themselves up as the writer struggles to convey something profound. Throughout her introduction, however, McKeon moves beyond this basic scalar understanding of the genre toward a more nuanced theory: that its limitations provoke writers to reflect, often meta-narratively, on “the faraway deep inside; . . . the faraway glancing off every surface” (vii). Short stories must contend with distance in spite of, or perhaps because of, the fact that there is very little of it available within the form itself. McKeon’s introduction, clocking in at a potent four pages, sets a standard for expansive contemplation done concisely, a standard that her selections meet through varied fictional means.

As one might expect, certain themes recur across these Stories on Distance: impending or recent death, spaces of travel such as hotels and airplanes, the surprising loneliness of cities, and migration. Pushing the idea of distance to its outer physical limit, two stories about space travel bookend the collection: the first, “Terraforming,” by the young Irish writer Elske Rahill, follows a woman into a training session for her upcoming journey to Mars. The story relies for its pathos on familiar space-related tropes like sadness over Pluto’s demotion from planet-status and fantasies about leaving the stress of earthly life forever. Despite resorting to these fairly broad strokes, the story treads boldly into territory that many of us earthlings can only imagine in the abstract: what it might be like to sign one’s entire life away for a project of interplanetary colonialism, or what exactly a training center for such a journey might look and feel like.

The story that closes the volume, Maria Takolander’s “Transition,” checks in on a protagonist who has advanced further in her dream of space exploration, a woman orbiting Earth in a small shuttle and beaming her experience back via satellite camera. The story begins with the line, “Nothing could have prepared her for this,” and the piece is as much about a gap between expectations and reality as it is about the abyss that separates her vessel from Earth, with its “white arteries of rivers, luminous oceans, bleeding deserts, the geometric scars of farmlands and cities; all protected by a radiant layer of atmosphere” (231). Takolander’s luscious descriptions of outer space, combined with her portrayal of the woman’s psychological and ultimately existential disorientation, make for a haunting closure to the collection.

In between these two stories on astronautic adventure (both of which, by the way, concern motherhood, suggesting that there might be an academic article to be written on metaphorical alignments of pregnancy and space travel), one finds an array of narrative styles on display, ranging from Sam Lipsyte’s and Yoko Ogawa’s dark comic realism to experimental ventures by Suzanne Scanlon and Gina Apostol. These latter stories concern relationships between authors (or artists) and the texts they’ve created. Scanlon’s contribution, called “The Rape Essay (or Mutilated Pages),” begins with a professor who pushes a Kathy Acker essay about acquaintance rape onto a female student-turned-lover-turned-psychiatric-patient. Scanlon’s story splices together narrative passages that reveal the disjuncture between the professor’s and student’s interpretations of the essay, interspersed with decontextualized question-and-answer lists and snippets from the student’s diary. As in Acker’s feminist writing itself, the story calls hermeneutic authority (represented, within the story, by the professor) into question by de- and then reconstructing the story on the student’s own terms. Like “The Rape Essay,” Apostol’s “The Unintended” requires a bit of page-flipping and rereading, made up as it is of numbered and titled short chapters that are sequenced out of chronological order. The stories of a translator, a famous filmmaker, his daughter, and his former wife intertwine in a tale that traverses decades and continents, while contemplating the ethics of documentary war photography. Among the selections in A Kind of Distance, Apostol’s story pushes most dramatically the limits of the short story’s formal constraints, which makes for a somewhat chaotic reading experience but could easily become the blueprint for a fascinating novel.

Elsewhere in the collection, one finds lyrical, ecologically-attuned narratives by Sarah Baume, Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, and Ross Raisin; accounts of two very different experiences of emigration by E.C. Osondu and Francesca Marciano; flash-fiction about moments of violence by Niven Govindren and Mark Doten; portraits of lonely city-dwellers by Porochista Khakpour and David Hayden; and difficult-to-categorize contributions by Kevin Barry and Kristín Ómarsdóttir. The latter story, translated from Swedish by Lytton Smith, might be the book’s strangest, as it portrays a day in the life of a couple who live “in a city which has done away with cash, in which payments are made through physical gestures” (146). As this line suggests, the story’s narrator seems charmingly unaware of how bizarre this story-world might appear to outsiders and makes no effort to account for or explain it. Though it would take a fair amount of interpretive strain to figure out what Ómarsdóttir’s story has to do with “distance,” its peculiar style of genre-blending—part dystopia, part parable—shimmers mysteriously among pieces that take a more transparent approach to McKeon’s assignment.

Reading through these stories, one’s grasp of what “distance” can mean may loosen, which provokes the question of what value a unifying theme confers on a short story collection if it may be interpreted so liberally. Short story collections typically take one of three forms: single-author compilations (e.g., The Stories of Frank O’Connor); nationally bounded anthologies (Penguin’s Modern Irish Short Stories); or best-of roundups that cull from journals and small magazines (the Best American Short Stories series). McKeon’s concept of bounding a collection by a theme has produced something of an outlier given these publishing trends, an assortment of texts diverse enough to introduce new writers and ideas while maintaining cohesive lines of inquiry—what is distance? how does it fit into the space of a few pages?—throughout.

McKeon’s approach to theme-based curation also allows her to place Irish writers (Barry, Baume, Ní Dhuibhne, Hayden, and Rahill) alongside writers from the Philippines, Nigeria, Finland, and other countries without having to explicitly contend with categories like “global” or “world” literature. From a scholarly perspective, this move does appear, however, to reflect the recent global turn in Irish Studies, as the breakdown of authors (one-quarter Irish, three-quarters from other places) produces not a truly comparative volume but rather a lineup of texts that one might find on a “transnational Irish fiction” syllabus. These weightier questions about canonicity and disciplinarity aside, however, A Kind of Compass is a beguiling and constantly surprising read, as well as a spur for contemplating the means by which humans find each other: across space, or national boundaries, or even the distance between words on a page.

[i] Frank Thomas Marzials, Life of Charles Dickens (London: Walter Scott, 1887), 91.