Town Stitched by River: Irish Writers at the International Writing Program. Edited by Alan Hayes and Christopher Merrill. Dublin, Ireland: Dublin UNESCO City of Literature, and Iowa City, Iowa: Iowa City UNESCO City of Literature and the International Writing Program, 2015, 96 pp.

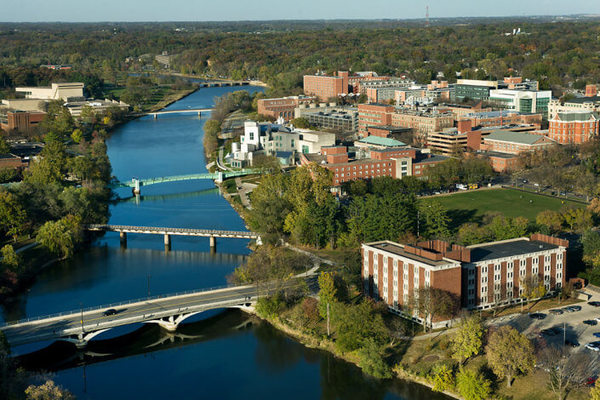

Town Stitched by River serves as a new anthology of creative writing by Irish alumni of the International Writing Program (IWP) at the University of Iowa, and it reinforces the connection between Dublin and Iowa City, two of the world’s UNESCO Cities of Literature. Featuring eleven writers who were in residency at the IWP between the years of 1978 and 2013, the collection was printed in a special edition of 320 copies, with a beautifully letterpressed cover. From a meditative personal essay by John Banville, to the gem-like images of Eavan Boland’s poems, to the Irish language poetry of Siobhán Ní Shíthigh, Town Stitched by River provides a rich and varied look at “the world we hold in common,” as IWP director Christopher Merrill writes in the introduction. Organized alphabetically rather than chronologically, the collection takes its title from the poem “Iowa City Sestina” by Nell Regan (79-80). It includes what is best about anthologies: there’s diversity in the genres and writing styles, prose laden with beautiful descriptions of the natural world and human interaction, and poetry that is imagistic or historical. The subject matter and themes presented vary, too, from the power of memory, to Irish women’s historical experiences, to how a sense of self is constructed for those with ties to a small country in a globalizing world. Due to the different ages of the writers gathered here, the perspectives presented are multi-textured. Thanks to the curating of Christopher Merrill and Alan Hayes, a few themes emerge to stitch this collection together.

Many of the collection’s essays, poems, and stories are concerned with the past, allowing their writers to process their own age and late stages of life. Many of these writers look back curiously at the previous generation and how their lives differ from the lives of those who came before. “Thinking back on the lives of one’s parents and making comparisons with one’s own life can be a dizzying exercise” (11), writes John Banville in “Awkward Age,” a simply-phrased personal essay about the anxieties of realizing that he is advancing in years. The essay is framed largely in questions: Banville wonders at what age his parents thought of themselves as old, how much his father resented his never-changing work schedule, why his mother “succumbed” to the Catholic church’s “absurd and petty commandment” to stop reading women’s home magazines (14), and when he will be disabused of his own conception of himself as a 37-year-old. Though the prose is simple, the essay is moving to the degree that these questions are pondered but left unanswered, fittingly.

Like Banville, Harry Clifton considers his age in his poems. He begins “Chez Jeanette” with a quote from W. B. Yeats, sitting alone in a crowded London shop at a moment of recognition of his age. Clifton aligns himself with Yeats’s position: “And so do I, past fifty now, / In the gilt and mirror-glass / Of Chez Jeanette’s immigrant bar. / […] Like Yeats’, but more of a mess” (43). He identifies, too, with his grandfather “cycling home from work / In the post-heroic age, / Quotidian” (42) and his great-grandfather, exiled from Ireland with the Irish Nationalist “Fenian putsch.” By writing through the lens of his ancestors’ experiences, Clifton presents a personally-inflected history of Ireland, but one that feels generally dim: “We are all anonymities, / No-one finds us” (44).

Paddy Woodworth’s “A Short Walk Through Stoneybatter” begins as a personal description of his Dublin neighborhood. As his walk continues, however, the essay takes on the flavor of an historical narrative, becoming less personal and more like historical nonfiction, which isolates it somewhat from the literary quality of the other essays. Yet there is much Irish history to be remembered and esteemed as Woodworth takes readers on a tour, from Viking Dublin and the Easter Rising to the Celtic Tiger and Belfast Agreement. He even pauses to close-read passages from Yeats while considering the Irish Literary Revival. The best of this essay consists not in the historical facts it presents, but rather in the moments when Woodworth probes how history has shaped the Irish national character today—for example, he stresses the importance of plurality in Irish culture and stories, despite the fact that England has “favour[ed] homogenous images of our culture” (89). He ends his essay (and the anthology) with a somewhat vague call to love rather than hate people in the modern world.

Desmond Hogan’s “The Spindle Tree”—one of the most beautiful pieces in the collection—also walks through recollections of the past by way of specific elements he recalls from the natural world. In fact, descriptions of the natural world could be said to form a second thread through Town Stitched by River. The evocative strength of Hogan’s piece is found in its formal innovation: it features a fragmentary sentence style and quick shifts between paragraphs, which mimic memory as well as botanical listing structures as he presents a glorious walk through the gardens of his childhood. He names specific flowers and trees, weaving together a portrait of this community. “The status, the remembrance of small towns has changed. But I remember it. I remember the spindle tree,” he writes, longingly (60).

Other writers also lean on the natural world to convey their ideas. Nell Regan’s poems are syntactically simple, with a light touch that stems from a naturalist’s eye. She is unique among the writers in the collection as the only one to include poems that specifically reference her time in Iowa City, as in “Iowa City Sestina:”

“This town is stitched by river—

that finds and winds its way through trees

whose leaves curl yellow and every poem

is found to contain it, them and cicada

call—perhaps they too stand for longing

forded by an imagined Atlantic bridge.” (79)

Regan’s poems are beautiful meditations on the self in nature, especially the relationship of the self to a natural environment that is not one’s own. Her poems indicate an openness to what nature might present: “dusk where a poem / or thought might constellate” (80). These poems come toward the end of the collection, reminding readers that the book came together thanks to this Midwestern city that unites these Irish writers.

Siobhán Ní Shíthigh is the only writer in the collection to include work in the Irish language. Though these four poems will be inaccessible to many readers, their place is uncontested; they bring visibility to this small language with a deep history. A translation by Thomas McCarthy (whose own poems fall just before Shíthigh’s in the collection, forming a fitting pairing) of one of the four poems is also included, acquainting readers with the poet’s use of metaphor and her interest in the religious life of people in small, Irish-speaking communities. Both Shíthigh’s and McCarthy’s poems rely on natural imagery; that of the sea. His translation of “The Witness of Foreigners” is full of simile and metaphor, negotiating loss and readjusting one’s thoughts to accommodate a changing world:

“My tears fall

Upon tea,

Light stretches like a sword

In the dark high tide.

An anchor drops

In the cove of my thoughts;” (74).

A final theme drawing this collection together is the often-difficult experiences of women in Irish history. Eavan Boland’s poems are a highlight of Town Stitched by River; they look to the lives of women close to home and in a larger historical context. The beauty of the poem “Amethyst Beads” is felt in the speaker’s use of the image of a necklace passed down from woman to woman, linking them to each other. “Art of Empire” places the speaker’s mother into the context of colonized Ireland:

“If no one in my family ever spoke of it,

if no one handed down

what it was to be born to power

and married in a poor country” (29).

The poem goes on to linger sadly on the reality of women in times past who were “skilled” in silence and who “never look up” (29). This recognition of traditional roles that silenced women or placed them below men is reminiscent of John Banville’s essay, too, in which he probes the experience of his mother, who first wore “slacks” as a “timid gesture towards the Women’s Movement that began in the 1960s” (11). He bemoans the fact that his father probably saw this gesture as an attempt to take power from men.

Sebastian Barry’s poems also focus on the experiences of Irish women, taking another tack by creating personas: his poems are each named for an Irish woman. His sketches of these women tap into well-worn stereotypes of Irish women as ruddy, simple, hard-working, and fertile. Perhaps more effective is Martin Dyar’s use of humor to build narratives that tell the story of the everyday lives of Irish people at different times in the nation’s history: “Mermaidism in the Donnelly house / was five sisters deep” (52).

It would seem that many of these Irish writers experience, as Woodworth expresses, a kind of “unease, of nostalgia for lost communal and spiritual certainties” (93). It’s a nostalgic collection overall. Perhaps that’s natural, given that the vast majority of authors represented here were born in the 1940s and 50s. It would be wonderful to see what a collection of the next generation of Irish writers would include. Sara Baume, for example, in residency at the IWP in 2015, just missed being included in the collection and has won multiple awards for her fiction. Nonetheless, Town Stitched by River has just the right variety in voices and writing style to keep readers engaged, while remaining united around the themes of memory, nature, and the women’s experiences. The collection’s beautiful descriptions and evocative portrayals of self and place will gratify readers who prefer personally inflected Irish histories written in literary poetry and prose.