Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fourteenth-century frescoes depicting the effects of good and bad governance in a city could be images taken from the pages of a picturebook. It is easy to construct a simple narrative based on the activities of the characters going about their everyday business, with both good and bad results, depending on which panel of the three frescoes is the focus. Lorenzetti was commissioned by the City Council in the Italian city of Siena to paint a fresco on the walls of the Sala dei Nove in the Palazzo Pubblico as a reminder of the importance of carrying out civic duties in a responsible and just manner. The work, now known as “The Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government in the City,” occupies three walls of the Sala. One wall shows the effects of good government, one the allegory of bad government, and another, between them, shows the allegorical figures of Wisdom and Justice presiding over the citizens.

When Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted his frescoes in the 1330s, Siena had become a wealthy city-state where struggles for power were frequent. It was a time when rural dwellers were arriving in urban centers in search of work and trading opportunities, and, at the edge of the “Effects of Good Government” panel, country people can be seen crossing a rural landscape to enter the walls of the city. In contrast to the calm note struck by the depiction of the effects of good government, the fresco describing the allegory of bad government strikes a jarring note. It shows a horned Tyrant presiding over the captive and bound figure of Justice at the bottom of the panel; the figures of Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War are on either side of the Tyrant, and the figures of Avarice, Pride, and Vainglory loom magisterially above. This allegorical mural was intended as a reminder of the consequences of failing to adhere to principles of right and just behavior, and like its companion pieces, is presented as a visual narrative to be interpreted by the reader/viewer.

Lorenzetti’s work is one of the first visual narratives depicting a cityscape and one of the most “realistic” depictions—albeit allegorical, and drawing on mythological references—of life in a city in pre-nineteenth-century visual art. The frescoes were painted before the invention of printing, and long before the emergence of the sequential visual narrative now referred to as the “picturebook,” but the analogous relationship between these frescoes and picturebooks is evident. Natalie Op de Beeck suggests that “the picturebook might be called a mural in miniature,” and compares it with the murals popular in the United States in the 1930s.[1] These were public reminders of the importance of maintaining community life in the face of a rapidly developing consumer society—not unlike the purpose of Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s murals. Picturebooks tend to reflect the dominant mores of the society that has produced them;[2] and John Stephens asserts that “children’s fiction belongs firmly within the domain of cultural practices which exist for the purpose of socialising their target audience.”[3]

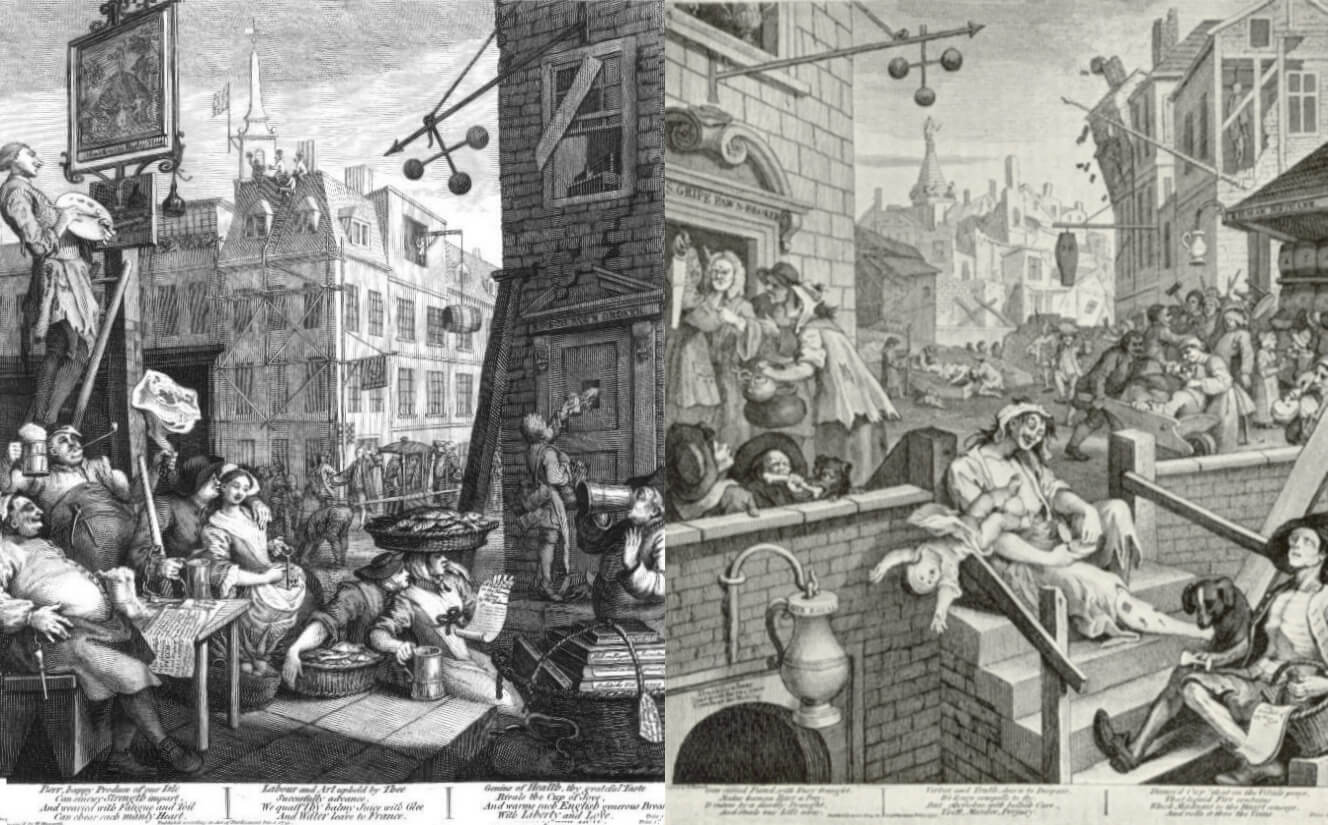

The city has long been a site of utopian/dystopian tensions, a theme mined both by writers and visual artists. The streets of London were portrayed as a site of immoral behavior by eighteenth-century artist William Hogarth in his etchings featuring the evils of drinking gin, in contrast to the benefits of drinking beer.

These images—in which children and adults succumb, both directly and indirectly, to the degenerative effects of gin-drinking—and other such images were often presented to children as exemplary of the results of bad or good behavior.[4] The woodcuts of Flemish artist Frans Masereel were patently not for young readers, but the influence of his wordless books resonates in subsequent visual narratives, including film and graphic novels, for children as well as adults. Masereel’s Die Stadt (The City)—a wordless picturebook for adults—was created as a result of the artist’s disillusionment with life in Europe during the interwar years.[5] Masereel’s woodcuts show in black and white a bleak vision of urban life: city streets look uncomfortably crowded, workers are exploited, and women are sexually objectified. Die Stadt maintains the city itself as the main focus, with various subplots involving characters who live in its darkly depicted urban landscape. Lynd Ward did something similar in Vertigo: A Novel in Woodcuts, but with a greater focus on the city’s inhabitants.[6] Ward also produced picturebooks for children that raized concerns about obsolescence and the progress of modernity.[7] Both artists, whose work referenced the aesthetics of Art Deco, were precursors and influences on the graphic novel, a form which has produced many brilliant examples of urban lives and landscapes, particularly in representing a darker side of urbanization.

This article is concerned with aspects of “the city” depicted in the visual narrative form generally classified as “picturebook.” These picturebooks tend to be more for younger readers than are graphic novels, though this trend is changing, and the two forms of visual narrative are increasingly drawing upon and influencing each other. The article moves from a discussion of urban landscapes depicted in visual texts both in general as well as those aimed specifically at a younger audience, to a discussion featuring specific titles. Picturebooks aimed at children under twelve (approximately) tend to show the city as either a neutral or a relatively favorable environment—where there are difficulties, the protagonist usually overcomes them. Often picturebooks favor a rural landscape, provoking a suspicion that they are host to a lingering romanticism. For many young people, however, the city is a challenging, even hostile, environment, and the number of picturebooks that confronts these specific concerns is small. Jenny Bavidge puts children’s alienation from urban life strongly, stating “[t]he clash of an idealized pastoral world of childhood with the stratifications and miseries of urban life is a standard theme in both realist and fantastic children’s fiction and film. […] children are routinely depicted as ‘out of place’ in urban settings.”[8]

Further, this article discusses cities and their inhabitants challenged by modernism/postmodernism, taking as examples Virginia Lee Burton’s Little House and Charles Keeping’s Charley, Charlotte and the Golden Canary, Railway Passage and Adam and Paradise Island.[9] It concludes by focusing on the city evolved into a menacing locus in Way Home by Libby Hathorn and Gregory Rogers, and The Girl in Red by Roberto Innocenti and Aaron Frisch.[10] The latter is a complex text, rich in visual imagery that conveys a great deal about the pervasive threats to a young female, and as such, it receives more extensive attention.

While their creators come from different countries, all of the books discussed reflect varying degrees of unease with city life, and all were first published in English. In each, the urban landscape is integral to the narrative, rather than the more usual neutral backdrop, or the transitional space in which events frequently occur in children’s books. Arguing that the central focus or setting of the story in many children’s books is often such a transitional site, and not a place in which people live, Naomi Hamer cites theorist James Clifford, who “discusses the liminal qualities of places ‘of transit, not of residence’ such as the ‘hotel, a station, airport terminal, hospital and so on: somewhere you pass through, where the encounters are fleeting, arbitrary’”—mostly these liminal spaces are contextualized in an urban setting.[11]

Any informal survey of picturebooks published in the last fifty years in English is likely to indicate that in general a rural or non-specific setting is more usual than a specifically urban one. Yet, as over half of the world’s population lives in towns and cities,[12] it prompts the question why city settings are not more common in picturebooks. There are exceptions, however, and two genres of picturebook featuring urban settings consciously aim to introduce a reader to city life. One tends to fall into a category between fiction and information book, in the form of Wimmel Bücher—books like those in Richard Scarry’s “Busiest People” series, in which characters mill about, engaged in various activities, rather as they do in Lorenzetti’s “Effects of Good Government,” and are a means of introducing young readers to people who perform different functions or jobs. The other genre increasingly available genre, generally published in series, are guides for a city visit in the guise of narratives. In these, the young visitor is seen strolling the streets and observing the sights in, as Kerry Mallan notes, “a sort of flânerie-styled tourism,” although, she continues, the role of tourist and flâneur “is not an easy amalgam.”[13] Often in these books there is a narrative, sometimes quite tenuous—a child or object that gets lost is common—or, as in the case of Miroslav Šašek’s books, the visitor relates anecdotes about the characters encountered as he or she explores the city. Although published before the current surge in this genre, Šašek’s series is among the most enduring and attractive.[14] Others have a stronger storyline, but with the intention of introducing well-known buildings and streets. A character is rarely threatened seriously by anybody or anything, and the city is shown as benign and welcoming. London, New York, and Paris are the cities which most commonly feature in these books, all popular locations in adult literature, too, and as opportunities to travel increase, more cities feature in the genre.

However entertaining or instructive they may be, books like these do not reflect the lives of actual children, and in the United States in the early twentieth century, educationists began to recognize the necessity for books which represented how real children lived. These were the years in which themes depicting urban life and industrialization gained momentum in American art, particularly in the work of the artists involved in the Ashcan School and the American Precisionist movement. Their influence began to take a hold on the American picturebook; H. Nichols B. Clark links these movements to ideas prevalent in education, especially those espoused by Lucy Sprague Mitchell (1878-1967) and others involved in the Bank Street Schools in Manhattan.[15] The philosophy behind these schools advocated stories that addressed children’s own circumstances—where they lived and what they experienced—including an emphasis on the urban environment and machinery. This influenced the creation of picturebooks which depicted a modern, industrialized society, albeit in some cases with anthropomorphized industrial equipment. The influence of Russian Supremacist and Constructivist art made itself felt too; in particular, a number of Russian artists who had emigrated to the United States began to forge careers as illustrators, and the influence of books and posters produced in the newly formed Soviet Union became apparent in the design and physical form of visual narratives.

Virginia Lee Burton (1909-1968) was a picturebook artist whose work was paramount in showing the tensions between the move from a low-tech, pastoral life to a highly mechanized way of doing things. Burton began her books with something mechanical or man-made, such as a steam shovel, a train, or a little house, implying satisfaction with how they functioned, before showing them in danger of being superseded by more advanced aspects of industrial and societal development.

Nathalie Op de Beeck refers to Burton’s The Little House as “a fairy tale of modernity”[16] and Barbara Bader describes it as “a record of urban decay and a brief for rural blessedness.”[17] In the opening pages, the anthropomorphized and feminized Little House stood alone on a hill, watching the changing seasons as the years rolled by and wondering what it would be like to live in the distant city. With the passage of time, urban sprawl engulfs the Little House, and now she nostalgically dreams of life in the country. In the city, change happens more and more rapidly, as first trolley cars, then an elevated train, and then a subway transport the increasing populace, until the Little House feels motion in all directions. The apartment houses and tenement blocks surrounding her are replaced by skyscrapers, so that the now boarded-up Little House could see neither the sun nor the moon and stars. As Op de Beeck points out, the Little House faces away from the massive buildings at her back, encouraging the reader to “reflect on Little House’s unwise, near-tragic curiosity about city life. The reader’s relation to the House is one of alarm, raising awareness of what is sacrificed to urban development.”[18] While the ending—in which the Little House is rescued by the great-great granddaughter of her builder, who organizes her transportation back to a solitary rural location—is more than unlikely, it offers a nearly universal image for children, attributing to the house, as Bader suggests, “the dimensions of legend,” for which “every left-behind rundown frame structure on a city street is the Little House.”[19] Burton’s endpapers provide a clue to her ambivalence about technology and modernism, showing the various modes of transport passing the Little House in her changing circumstances, from conveyance by horse to bicycles to motor vehicles, ending in a neat reversal, with a final image of a horse transported by truck—“Horse Pullman”—moving in a left-to-right direction off the bottom right-hand corner of the cover. Burton’s picturebooks explore the dichotomy between stasis and development, which, as Op de Beeck remarks, “suggests that the here-and-now city can be an inhospitable place for old-fashioned types or for those unwilling or unable to adapt to the latest technologies.” Implicit, as Op de Beeck points out, is a warning that while development must happen, there is a need for caution.[20]

In Europe, shortages of paper as well as other constraints hindered the production of picturebooks in the years between the wars and during World War Two, when cities were bombed, rather than celebrated in books for children. While it is an information book, it is interesting to note that Village and Town,[21] number sixteen in the Puffin Picturebook series, which was published during the War, carries an image of a traditional-looking English town on the front cover. Dominated by a squat church tower and ruined abbey, this could, broadly speaking, be a representation of many country towns throughout England. On the back cover, however, is an image of St. John’s Wood underground station in London, opened in 1939, just three years before Village and Town was published in 1942. This choice of cover image placement says something about perceptions of cities and modernization in Britain in the 1940s, indicating a valorization of rural over urban. It also suggests that the publisher may have had reservations about putting an image on the front cover in which a large white block of flats—long-since demolished—dominates the attractively curved station frontage.

Tower blocks, much more brutally designed than the one in St. John’s Wood, came to epitomize many of the changes to urban life in 1960s Britain. The decade saw the rise of social realism in the English novel, as well as a society that was beginning to feel the effects of greater equality in terms of education and health care. Authors, illustrators, teachers, and librarians were products of this more modern, flatter society, but change was slow to come to children’s literature, and especially to picturebooks, which, in part due to production expenses, tend to be reticent in adopting new ways.

It was not until the 1960s that the British picturebook began to come into its own; Charles Keeping (1924-1988) is one of the artists most associated with the portrayal of urban life in this period. Keeping was an East Londoner through and through, and his affectionate view of the small streets and their inhabitants in the area around Vauxhall Walk where he grew up characterizes the children’s books he wrote and illustrated. Keeping was a master lithographer and draftsman, and these skills inform his work, in which stylistic changes occurred throughout his career, responding to his own desire to innovate and experiment, and to developments in printing processes. His earlier work for children, produced in the 1960s when methods of color printing were advancing, shows remarkable bursts of color, with a tonal intensity that is almost violent at times in Charley, Charlotte and the Golden Canary, the first of his books to be awarded the UK Library Association’s Greenaway Medal. Keeping uses color as well as line to express his reaction to the sight of children high on the balconies of newly built tower blocks in the Elephant and Castle area of London. The children were safe and well-cared for, but for Keeping, they were as captive as the canaries in cages hanging from balcony rails, since they could no longer play in the built-up streets where a sense of neighborhood had been lost.[22]

Later titles leaned toward abstract expressionism and a moderation of color intensity; pages were often monochrome, but changing color from page-opening to page-opening intensifies mood and character. Keeping used his ability as a draftsman to humorously limn familiar London characters in books such as Railway Passage and Sammy Streetsinger.[23] His eye was wry in capturing the foibles of “types” who at one time could be seen on the streets of many cities, but his affection for difference and for outsiders, old and young, prevails. Yet, critic Bob Dixon was less than complimentary about Keeping’s Railway Passage, a story of eight “old and poor people who live in the Passage and who are called aunts and uncles by the neighboring children.”[24] Dixon takes the story of how these neighbors dispose of their very substantial win on the pools rather literally, and he seems shocked by some of Keeping’s visual depictions of them. It is not one of Keeping’s best books, but its depiction of aging members of a London community is significant, and it may be read as a gentle parable with an underlying degree of irony. The vision of Auntie Meanie in her new clothes, looking like a geriatric burlesque artist is humorous; the image, which shows an old woman dressed as she wishes, not as society decrees she should be, is described by Dixon as “a revolting picture [that] accompanies the text.”[25] Perhaps it is also a case of how a visual narrative is interpreted. In Keeping’s work the text accompanies the images which are always in lead position, rather than the other way around; his stylistic approach and the media he chose for each book capture his chosen scenes and characters more tellingly than does his slight text.[26] Keeping maintained an empathy with the characters, old and young, who populated the area around Vauxhall and Lambeth, and in these books he shows both people and buildings affected by change.

Characters like Auntie Meanie have now vanished from city streets, and children, like Charlotte, live in suburbs or high in flats that remove them from the sort of knockabout experiences that were part of growing up for city children, such as Keeping, in earlier times. His last book, Adam and Paradise Island, takes place on a small river backwater, the eponymous island, when the council decides to replace the small shops and old warehouses with a motorway and supermarket. The local children react by building a playground on the island, and Keeping largely leaves his images to show change coming to the island, having remarked on another occasion that “[c]hildren can see that this is a real issue, and by putting it into a drawing you actually give them something to think or talk about and draw their own confusions from, over and above just making a story of it.”[27] Keeping does not reject the march of modernity, however, and a compromise is reached when a portion of land is retained as a playground due to the children’s initiatives.

Cities lend themselves to mysterious narrative envisioning: dimly lit alleyways hold more possibilities than brightly lit boulevards. Danger has always been part of city life and artists like William Hogarth and Frans Masereel vividly encapsulate horrors of urban living. While some of the excesses they depict are no longer common on city streets—in some cases they have moved indoors or elsewhere—potential danger is always a reality. Jenny Bavidge points out that “[t]he city is commonly depicted (and has a long history of being so) as an environment that operates to entrap and endanger children.”[28] Picturebooks which engage with such dangers are the antithesis of the Wimmel Bücher or the tourist-flâneur picturebooks. Two such picturebooks were published almost twenty years apart, but in each the young protagonist is shown traversing streets where danger lurks, and in each, society seems to have a negligent attitude towards young people.

The earlier book, Way Home, written by Libby Hathorn and illustrated by Gregory Rogers, was published in Australia in 1994, and for his artwork Rogers was awarded the Kate Greenaway Medal. While widely acclaimed, it has attracted controversy because of its bleak depiction of homelessness, and because a woman who could be a prostitute—to surmise this possibility, an adult awareness is required—speaks to Shane, the homeless boy at the narrative’s center.

On the front cover, Rogers’s charcoal and pastel images are dark, prompting the reader to look closely at a boy running along a busy city street. The title is double edged: Shane does not have a home in the sense of a place where he is cared for, although this is not revealed until the final page; rather, “home” is the small shelter that he has made his own and where he will care for the kitten he has rescued. The verbal text on the cover and throughout the book is white on a black surface with a jagged white edging, looking like ripped paper, suggesting the darkness of Shane’s torn-apart life. The opening double-spread shows him darting down a deserted alleyway where he finds a kitten. He tucks the kitten into his zipped jacket, and the following linear narrative shows him traversing the city as he takes the kitten “home”: “You’n me, Cat. And we’re going way away home […].”[29] The text is punchy, catching the register of the boy’s voice, and mostly consisting of Shane’s running commentary to the little cat.

Danger and detritus mark his route; Shane needs his street-savvy skills to avoid a waiting gang and heavy traffic on the streets. Consumerism confronts the homeless boy: a white fat cat disdainfully stares from a window, in a Jaguar car showroom expensive models gleam, a Chinese restaurant looks inviting. The boy comments to the cat about all of these, and a waiting woman (sex-worker?) who greets Shane indicates that he is not a newcomer to the street. When a large dog scares the cat, it jumps into a tall tree, giving Rogers an opportunity to show “the rise and fall of the big sea of city below”;[30] then, back on the ground they run again before crawling through a hole in a fence, into Shane’s home, a shelter lined with newspaper, where the boy assures the kitten they will be safe.

The ending is not conclusive, but is more realistic for being so. Boy and cat reach safety, but readers will have questions. Will the kitten stay with Shane? Why is he homeless? What will happen to them both? The streets and alleys of the nameless city are Shane’s territory. He is shown as streetwise and confident, but the drawing of a cat pinned to a wall, and a cat’s face on a cushion, hint that he will be glad of the kitten for company.

The Girl in Red, Roberto Innocenti’s syncretic version of the Little Red Riding Hood story, also has a protagonist who traverses a big city, but Innocenti’s means of drawing the reader into the narrative is quite different from Way Home. For one, the reader engages with Shane as he dashes through streets and alleys with the little cat. Consumerism and urbanization, too, are evident, as are their corollaries—bins overflowing with waste, heavy traffic, indifferent passers-by—but Shane, in Way Home, is undoubtedly in control. In The Girl in Red, however, the reader is positioned as a watcher, analogous to the hunter who watches Sophia in her red coat. Innocenti and Frisch have created an allegorical version of the “Little Red Riding Hood” ur-story in which the threats implicit in the hyper-consumerism and depersonalization of an uncaring metropolis are shown in opposition to the trope of the innocent young girl.

Roberto Innocenti (born in 1940) is an Italian artist who has won many awards for his work, including the Hans Christian Andersen Award. His picturebooks tend to be for older readers, and he is not afraid to tackle difficult themes, including Nazi concentration camps in Rose Blanche and Erica’s Story.[31] Aaron Frisch is a U.S. author who has put words to Innocenti’s story.

The voice of Sophia, the girl, is not heard; the reader watches her, fears for her, grieves for her, understanding from the start that no good will come of this journey through the metropolis. Throughout the book, the verbal text is displayed in white on red or grey panels, and all of the images are framed in white, highlighting their depth and color, emphasizing Innocenti’s characteristically detailed artwork; and while this artwork provides distance from the grim tale, it intensifies the sense of menace in the streets. Hathorn and Rogers help the reader to empathize with Shane, and while readers may fear for him, the boy’s competence to look after himself seems assured. Sophia, on the other hand, is a distant figure, Innocenti’s hyper-realistic artwork pitching her as a victim from the start. On the front cover, dressed in a red coat and pixie hat, she is watched by two graffiti eyes, wide open in surprised concern, while a cat on a rubbish bin, distracted from a fish bone, looks askance as she passes by. On a corrugated iron gate there is an image of a dog with bared teeth—presumably a keep-out warning—but in this story it might also be a wolf.

The Girl in Red contains a prologue and an epilogue, framing and providing distance from a potentially disturbing narrative, while emphasizing its traditional status—this is a story set apart from ordinary time, reminding us of its oral origins. The prologue consists of a large image before the title page showing a group of children gathered around a table on which an old crone is seated on a plinth. She is much smaller than the children and is lit-up from below, like a toy-figure, as she invites them to draw close, offering to “weave you a tale.” Strewn round the room are signifiers of what is to come. A blonde-haired doll, dressed in a sexy outfit, lies blindfolded on the floor; correspondingly, across the room, a blindfolded Mr. Punch, complete with truncheon, sprawls out of a puppet theater, a human leg hangs out of the jaws of a model shark, and an action man figure dressed as a guerrilla fighter with a machete and gun lies on the table. Innocence is hinted at by a child lying in a traditional wooded cradle, a dancer on a wind-up musical box, and other old-fashioned toys which sit on the shelves behind the old woman.

After the title page, which carries the same image as the cover, a double-page spread shows the outside of a group of flats in a large block. The narrator’s voice speaks:

Our story takes place in a forest. This forest has few trunks and leaves—it is composed of concrete and bricks instead. In the day, and especially in good light, the dwellers live contentedly enough, to each their own. Among them, at the edge of the forest, is quiet girl named Sophia.[32]

The flat occupied by Sophia is shown in the middle, not at the edge, of the complex, contradicting and destabilizing the verbal text. On the next page, we learn that Sophia lives with her mother and younger sister. Her Nana is not well, and Sophia is sent to keep her company, with her mother’s injunction to “Stay on the main trail all the way.”[33] It is evident that the family lives in a poor neighborhood and that the city, which is conflated with the forest, is frenetic, crowded, and impersonal: “Everyone sees you, but no one does.”[34] As Sophia reaches a large shopping center called “The Wood,” consumerism is increasingly apparent. Shoppers crowd the walkways, a Santa Clause figure clutches a bag that looks more like loot than bounty, children consume quantities of junk food, and advertisements are everywhere. The image reflects Bavidge’s observation that “[a]ds can draw on the rhetoric of urban threat and danger to purity, and a discourse of dirt/cleanliness which also has racialized overtones.”[35] It may be that an election is near, as one ad declares “Arrogance is power”; across from it, another poster bears a picture of a grinning Silvio Berlusconi lookalike candidate, an image that gestures to all that it implies about attitudes towards women. Female images are commodified and oversexualized, and mannequins in shop windows are dressed in sexually suggestive garments, evidence of Elizabeth Marshall’s proposition that “Innocenti uses this visual language of contemporary advertising and its reliance on soft-core heteroporn in the streetscape through which Sophia travels.”[36] Marshall continues by commenting on how incongruous these familiar sexualized advertisements are when they appear in a children’s picturebook: “[t]he fairy tale picturebook format, a genre generally associated with childhood, is constantly ruptured by images of hyper-sexualized girl dolls and by representations of adult women who appear in images of advertisements as fragmented body parts, including lips, legs, breasts and buttocks”; these “images of the dismembered parts of women’s bodies foreshadow the wolf’s desire to devour Sophia into bits and pieces.”[37]

Sophia traverses the streets and “The Wood” without, it seems, taking much notice of all the visual clutter around her, until she reaches her “favourite display,” the “window of wonders.” Here she pauses in front of a gender-specific display of toys: male action figures and weaponry, and sexualized female dolls: “before her are monsters, princesses, dark fates and happily-ever-afters. Images of the past and of the future.” One of the few “old-fashioned” toys in the window is a wind-up Red Riding Hood, dressed in a similar coat and cap to Sophia’s. Exactly in Sophia’s line of gaze—she holds up a flower, indicating Sophia’s immanent deflowering, and signaling a likely finale to her story—is a woodman’s knife plunged into a pool of blood on a white block.

Distracted by the window, Sophia loses her trail, finding herself outside “The Wood” in a bleak, rundown area populated by waif-like children and “jackals,” tough youths on motorcycles who surround the bewildered girl. The rain falls, but, “with a clap of thunder, the jackals are gone,” frightened away by a black-clad superhero figure who towers above them from a vantage point on a wall. Sophia, abject, cowers before the imposing strong-jawed hunter, wondering at his big teeth, while behind her another advertisement for the Berlusconi lookalike, gazes down at her. The hunter brings Sophie part of the way to Nana’s, but leaves her to make the rest of the journey herself. Meanwhile, a glimpse of his coat as he slips into Nana’s trailer may be noticed. Reaching the trailer, Sophia pauses at the closed door, leaving the reader to wonder if she has noticed the hunter’s motorbike parked at its side. In the next opening, Sophia’s mother is shown on the verso, silhouetted in the light from the doorway of her flat in the otherwise dark block. On the recto, the hunter, now transformed into a wolf, flees on his motorbike, evading the police cars arriving at the trailer. The next opening shows heavily-armed police surrounding the trailer on the verso, while one image on the recto shows the hunter-wolf with the “jackals,” with accompanying text: “wolves and jackals are not so different. They have the same wicked grins.” The other image shows Sophia’s mother on her balcony, while the text says “[t]he clouds will allow no sun today.” Then, with another page-turn, an alternative ending is offered, as the old woman who introduced the story tells the listening children their tears are not necessary, and a final image shows hyper-masculine police surrounding the trailer and stuffing the hunter into a police car, while Sophia, her mother, and Nana are interviewed by one of a pair of exaggeratedly sexualized female reporters on the scene. Tellingly, in the background, a tower block, which in previous images carried a sign stating Gold Co., Inc., is now bare, and a sheriff holds a placard proclaiming “Happy End.” Commenting on this scene, Innocenti has explained that the “Happy End” is an ironic reflection on some people’s belief that they live in a story on television. With this book, he wanted to make “a clear accusation of society and certain sorts of people” and, by doing so, to encourage debate through his books.[38]

In all of the texts discussed, the city is depicted with a degree of ambivalence. This ranges from Virginia Lee Burton, Lynd Ward, Charles Keeping, and other illustrator and authors of the early and mid-twentieth century, whose work recognizes the inevitability of urbanization and innovation but also regard it with a degree of caution, to more recent books that present a harsh, and sometimes violent, cityscape.

Burton’s Little House suggests a return to rural values, while, on the endpapers she subtly recognizes that changes happen. Keeping is a sturdy realist. His work indicates regret at the limits on outdoor play imposed on children who live in high-rise blocks of flats, but his recognition of the need for compromise between development and a place to play is evident in Adam and Paradise Island. In Keeping’s texts, the city and its inhabitants are threatened by changes that may not bring improvements for everyone, but which he accepts as inevitable. Hathorn and Rogers show the city as a hostile environment for a homeless boy, but leaven it with the friendliness of the prostitute, as well as Shane’s own ability to adapt to living in a squat, difficult though that may be.

Innocenti and Frisch gesture to the result of failings in the political system—chiming with Lorenzetti’s “Bad Governance” fresco—by means of election posters, suggesting as they do a notoriously corrupt Italian politician, and in the contrasting scenes of excessive affluence and desolate cityscapes. Both The Girl in Red and The Little House hark to traditional moral or cautionary tales, respectively advocating that “home” is best (especially when it is rural one), and that children should do as their mothers tell them. Keeping’s books and Way Home are more realistic; in the case of Keeping’s work, the city is identified as London, and the cityscape in Shane’s story conforms to that of many cities worldwide. All of these are picturebooks that have something significant to say about life in a big city, contrasting with the cheerful Wimmel Bücher and touristic flâneur texts that predominate the market, the purpose of which are to inform and entertain.

Lorenzetti’s frescoes have lasted for almost eight-hundred years, and their visual argument for good governance is still relevant in the twenty-first century, as is their warning about the effects of bad governance. Like the frescoes, there is much in the books discussed in this article that suggests the virtues of a culture that values the individual while recognizing the importance of a just society. Yet, they are not didactic, and can appeal to children on levels, sometimes thought to be beyond their capacity. These books demonstrate how picturebooks of a high artistic standard can provoke reflection, and even argument, while respecting the reader’s intelligence and ability to interrogate prevailing ideologies.

[1] Nathalie Op de Beeck, Children’s Picturebooks and the Fairy Tale of Modernity (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 169.

[2] Exceptional picturebooks often break from perceived notions of what is acceptable for children, although as society changes, these may later be celebrated. An example is Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. When it was first published in 1963, it received critical comments suggesting it encouraged misbehavior, as well as being likely to scare children. For further details, see Selma G. Lanes, The Art of Maurice Sendak (1980; New York: Abrams, 1993), 104.

[3] John Stephens, Language and Ideology in Children’s Fiction (Harlow: Pearson Education, 1992), 8.

[4] Hogarth was prompted to produce these etchings by the uncontrolled consumption of gin, which was frequently impure, by those living in city slums. The effects of gin-drinking in the poverty-stricken parish of St. Giles includes infanticide, prostitution, hunger, and death. In contrast, Hogarth depicts diligent citizens enjoying good British ale after a day’s work,

[5] Frans Masareel, Die Stadt (München: Karl Wolff Verlag AG, 1925).

[6] Lynd Ward, Vertigo: A Novel in Woodcuts (New York: Random House, 1937).

[7] Ward’s picturebooks include Stop Tim! The Tale of a Car and The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge; see May Yonge McNeer and Lynd Ward, Stop Tim! The Tale of a Car (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1930); and Hildegarde H. Swift and Lynd Ward, The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge (New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1942).

[8] Jenny Bavidge “Vital Victims: Senses of Children in the Urban” in Children in Culture, Revisited, ed. Karín Lesnik-Oberstein (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 209.

[9] See Virginia Lee Burton, The Little House (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942). See also Charles Keeping, Charley, Charlotte and the Golden Canary (London and New Yok: Oxford University Press and Franklin Watts, 1967); Keeping, Railway Passage (London: Oxford University Press, 1974); and Keeping, Adam and Paradise Island (London: Oxford University Press, 1989).

[10] See Libby Hathorn, Way Home, ill. Gregory Rogers (Milson’s Point: Random House Australia, 1994); and Roberto Innocenti, story and ill., and Aaron Frisch, The Girl in Red (Mankato, MA: Creative Editions, 2012).

[11] Naomi Hamer, “The City as a Liminal Site in Children's Literature: Enchanted Realism with an Urban Twist,” The Looking Glass 7.1 (2003). Books set in the subway are a good example of this “transitional space,” and these are now so numerous that they are almost a subgenre.

[12] According to the World Health Organization “[t]he urban population in 2014 accounted for 54% of the total global population, up from 34% in 1960, and continues to grow. The urban population growth, in absolute numbers, is concentrated in the less developed regions of the world. It is estimated that by 2017, even in less developed countries, a majority of people will be living in urban areas.” See “Global Health Observatory (GHO) data,” World Health Organization, last accessed July 23, 2016, http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/situation_trends/urban_population_growth_text/en/.

[13] Kerry Mallan, “Strolling through the (Post)modern City: Modes of Being a Flâneur in Picturebooks,” The Lion and the Unicorn 36.1 (January 2012): 56-74.

[14] Šašek (1915-1980) was a Czech artist whose This is… city series was critically acclaimed when published in the 1950s and 1960s. A number of titles were reissued in the 2000s.

[15] H. Nichols B. Clark, “Here and Now, Then and There, Stories for Young Readers” in Myth, Magic and Mystery: One Hundred Years of Children’s Book Illustration, ed. Michael Patrick Hearn, Trinkett Clark, and H. Nichols B. Clark (West Boulder, Colorado: Robert Rinehart, 1996), 85.

[16] Op de Beeck, Children’s Picturebooks, 177.

[17] Barbara Bader, American Picturebooks from “Noah’s Ark” to “The Beast Within” (New York: Macmillan, 1976), 201.

[18] Op de Beeck, Children’s Picturebooks, 180.

[19] Bader, American Picturebooks, 202.

[20] Op de Beeck, Children’s Picturebooks, 170.

[21] S.R. Badmin, Village and Town (London: Puffin Picturebooks, 1942). The series, an offshoot of the successful Penguin Books, was the initiative of Noel Carrington, who had become aware of auto-lithographic printing methods which produced high-quality colored paperback children’s books at a low cost in Russia and France.

[22] Douglas Martin, Charles Keeping: An Illustrator’s Life (London: Julia MacRae Books, 1993), 96.

[23] See Keeping, Railway and Keeping, Sammy Streetsinger (London: Oxford University Press, 1984).

[24] Bob Dixon. Catching Them Young 1: Sex, Race and Class in Children’s Fiction (London: Pluto Press, 1977), 50-1.

[25] Ibid., 51

[26] More may be read about Keeping’s style and technique in Martin.

[27] Keeping, in an interview with Douglas Martin; quoted in Martin, Charles Keeping, 115.

[28] Bavidge, “Vital Victims,” 211.

[29] Hathorn, Way Home, 3.

[30] Ibid., 12

[31] See Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan, Rose Blanche (London: Jonathan Cape, 1985); and Roberto Innocenti and Ruth Vander Zee, Erica’s Story (Mankato: Creative Editions, 2003).

[32] Innocenti and Frisch, Girl in Red, 1.

[33] Ibid., 2.

[34] Ibid., 3.

[35] Bavidge, “Vital Victims,” 212.

[36] Elizabeth Marshall. “Fear and Strangeness in Picturebooks,” in Challenging and Controversial Picturebooks: Creative and Critical Responses to Visual Texts, ed. Janet Evans (London: Routledge, 2015), 160-177.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Roberto Innocenti (public discussion, Bologna Children’s Book Fair, Bologna, Italy, March 26, 2013).