This article examines theatrical representations of the Great Hunger and Irish Famine migration that were performed during the era of the Celtic Tiger and its collapse. More specifically, I will argue that the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger can be traced through shifting patterns of remembrance and thematic preoccupations in contemporary Irish theater productions about the Great Famine. I want to suggest that characters in these works serve as palimpsestic “figures of memory”[1]: they embody anxieties about how Irish prosperity was implicated in increasing global inequality during the boom, and about the deteriorating prospects for Irish youth following the crash. Moreover, I will consider the performance of Famine remembrance in light of theoretical models, such as Steve Garner’s “historical duty” argument and Joseph Roach’s notion of “surrogation,” to assess the significance of their converging temporalities on stage.[2]

A secondary objective of this article is to revisit claims that I have made about the relationship between performance and migrant remembrance in light of recent theater criticism by Kathleen Gough, Sinéad Moynihan, and especially Charlotte McIvor that exposes the limits of “historical duty” as a vehicle of empathy and its potential for cultural appropriation. “In Irish performance, art and public discourse,” notes McIvor,

asylum seekers and refugees in particular have not only been seen as “Others” but frequently cast as contemporary proxies for the restaging and correction of traumatic Irish histories (such as the Great Famine and mass emigration). As Jason King argues, “it is in the very act of remembering that an imaginative space of sympathetic engagement is created for the expression of cross-cultural solidarity between newly arrived immigrants and former Irish emigrants.” King’s statement suggests that historical duty is not reserved only for asylum seekers and refugees, but frequently extended as a concept covering all migrants.[3]

McIvor argues persuasively that Irish audiences are often encouraged to feel empathy for immigrants through the prism of their own traumatic past, rather than engaging with them on their own terms. “Contemporary asylum seekers, refugees and migrants […] find themselves cast,” McIvor suggests, “in the role of proxies for the dead as supplicants for a better future that […] can be shaped by Irish citizens for themselves now.”[4] Indeed, McIvor provides an important reminder that relations between performance and remembrance are often fraught, and that the conflation of different categories of migrants tends to flatten out the experiences of asylum applicants and refugees that she has endeavored to recuperate in her groundbreaking research.[5]

Nevertheless, this article examines the sudden disappearance of “a better future” during the collapse of the Celtic Tiger, as registered in theater productions about the Great Hunger. After a brief survey of the genealogy of Famine performances, I will first explore Donal O’Kelly’s The Cambria (2005) and Elizabeth Kuti’s The Sugar Wife (2005) as key works that juxtapose plotlines set in 1840s Famine Ireland with the arrival in the country of former African-American slaves who embody concerns about global inequality, conspicuous consumption, and the treatment of asylum seekers and immigrants at the height of the Celtic Tiger. I will also suggest that these plays implicate their audiences as beneficiaries of globalization by contrasting current Irish privilege with historical privation. In the second part of the article, I will further argue that the collapse of the Celtic Tiger prompted a change in register in the performance of Famine remembrance in theater productions since 2008. More specifically, it is my contention that the predicament of Famine emigrants becomes a central preoccupation of these works—a grand narrative, and a metaphor for Irish youth seemingly wrenched from a prosperous nation to confront diminished expectations and self-images of deprivation from the past. The re-imagined plight of expendable young people provides the impetus for dramatic re-enactments of the Irish Famine migration by a variety of community organizations, youth groups, and professional theater companies. They include DruidMurphy’s 2012 revival of Tom Murphy’s Famine (1968), Jaki McCarrick’s Belfast Girls (2001), and Fiona Quinn’s The Voyage of the Orphans (2009). All of these plays dramatize the experiences of Famine emigrants and metaphorically compare the predicament of their orphaned protagonists with the diminished prospects for their youthful casts. They also suggest the futility of mass-migration as a remedy for national catastrophe.

Famine Processions

Current productions about the Great Hunger and Irish Famine migration can also be traced through a genealogy of performance to nineteenth-century popular culture and a repertoire of ritualized gestures of protest against privation and hunger. Before the Famine, one of the most emblematic images of communal revelry against the threat of scarcity is conveyed in Nathaniel Grogan’s painting Whipping the Herring Out of Town (c. 1800), on display in the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork. It is a painting that illustrates a ritualized moment of communal performance in Cork, an Easter procession and celebration of plenty and prosperity during which a herring was hoisted on a rod and paraded down to the River Lee to mark the end of Lent. As Dawn Williams notes, “The painting depicts the moment after the herring is discarded, when the butchers would tie a quarter of lamb to a lath, decorated with ribbons and flowers, which would then be accompanied on its return to the market place by musicians, revellers and mischief-makers.”[6] It is a carnivalesque image that brings people together regardless of age, class, or gender in a festive display of social cohesion and dietary and liturgical customs that marks the return of plenty and signifies the end of want.

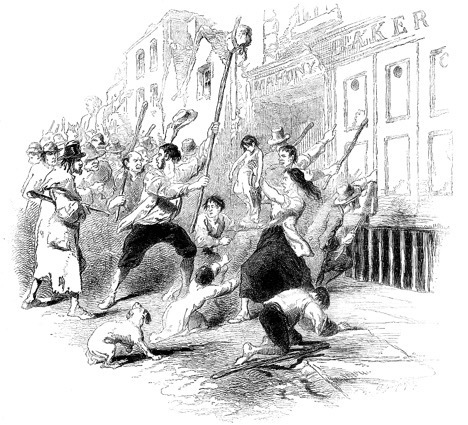

Yet this ceremony of abundance in Whipping the Herring Out of Town also bears a striking resemblance to the performance of scarcity by hungry processions during the onset of the Great Hunger. On October 10, 1846, the Pictorial Times depicted a food demonstration in Dungarvan, County Waterford, in which a stale and withered loaf of bread was hoisted on a poll in place of a more delectable foodstuff.[7] As Ciarán Ó Murchadha has noted, the spectacle of “a man holding up a spade to which was affixed a loaf of bread [was] the traditional manner in which impoverished communities indicated the presence of starvation in their midst.”[8] On April 24, 1846, Royal Irish Constabulary Inspector George Minehan was confronted in Skibbereen by a crowd “consisting of the lowest order, […] preceded by a man who exhibited a spade with a loaf of bread on it, signifying want of labour and want of food.”[9] A similar spectacle was recorded in the Cork Examiner on September 4, near Mallow, which “presented one moving mass of human beings […] headed by a tall and able-bodied man, bearing in his hand a wand with a tainted potato on the top, emblematic of their blighted prospects.”[10] Whether it is the exhibition of a “tainted potato” or a “loaf of bread” on a spade, these performative gestures signify the deprivation of Famine processions. Their self-conscious displays of scarce and tainted foodstuffs are intended to be “emblematic” of the “blighted prospects” of a people and a nation, and to become synecdoches for the starving masses who march behind these withered standards. As the shriveled talisman of a hungry people, the “tainted potato” and hoisted bread also represent an implicit threat of violence, if the “want of labour and […] food” for their bearers is not soon met. They have a performative function to mediate between the starving masses and the assembled spectators who might remedy their plight.

These conspicuous displays of plenty and privation can also be traced through a genealogy of performance from the 1840s to contemporary Irish theater. In The Archive and the Repertoire, Diana Taylor distinguishes between what she terms “archival memory” and that of the repertoire, which “enacts embodied memory: performances, gestures, orality, movement, dances, singing—in short, all those acts usually thought of as ephemeral, nonreproducible knowledge.”[11] Nathaniel Grogan’s painting and the Pictorial Times illustration are, of course, examples of archival images, but they also attest to a repertoire of customary practices, performative gestures, and the embodied memory of privation and plenty that is marked in the very different Easter and Famine processions they depict. Their contrasting displays of succulent lamb and desiccated bread signify the abundance and collapse of the food supply.

The ephemerality of this memory and performance of dearth is also transmitted in various historical and contemporary theater productions. As Chris Morash has noted, there is no “canon” of plays about the Great Hunger as such. “[W]hat is arguably the most important, certainly the most traumatic, event in modern Irish history has been conspicuously absent from Irish stages,” he suggests.[12] Indeed, Morash contends that “there are only two Famine plays written before 1900”[13]—Hubert O’Grady’s The Famine (1886) and W. B. Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen (1892)—and then only seven professionally produced twentieth-century plays about the Great Hunger before the mid-1990s. He lists these productions as Maud Gonne’s Dawn (1904), Padraic Colum’s The Miracle of the Corn (1908), Gerard Healy’s The Black Stranger (1945), Tom Murphy’s Famine (1968), Eoghan Harris’s Souper Sullivan (1985), John Banville’s The Broken Jug (1994), and Joe O’Byrne’s The Last Potato (1994).[14] As late as 2008, Morash claimed that “the theatre of the Irish Famine is a theatre that has never been realized” but only “gestured towards, somewhere offstage. Perhaps it will remain so in the era of the Celtic Tiger, as an entire generation are now growing up never having known high unemployment, emigration, or deprivation.” “Without a referent, the possibility of an Irish Famine theatre in extremis fades,” he added: “in a culture of success” that was not propitious for its development.[15]

Irish Theater, the Famine Migration, and “Historical Duty” in the Celtic Tiger Era

Since 2008, the collapse of Ireland’s Celtic Tiger economy has been registered in a proliferation of new plays about the Great Hunger that have found their referent in the sudden resurgence of emigration, unemployment, and deprivation. The sesquicentennial of the Famine in the mid-1990s, the onset of immigration into Ireland, and the rise of the Celtic Tiger had also inspired a number of Famine-themed plays. One of the most remarkable of these was Jim Minogue’s Flight to Grosse Ile, which was performed by the Mountjoy Theatre Project in Dublin, in April 1999, as I have discussed elsewhere.[16] The production was significant because it gave early expression to what Steve Garner has termed “the historical duty argument”:[17] the idea that Ireland’s historical experience of colonization and forced emigration has made the Irish empathetic to other people undergoing similar struggles, because asylum seekers and refugees resemble, in Garner’s phrase elsewhere, “the economically- and politically-persecuted Irish of other times.”[18] As Garner has influentially argued in Racism in the Irish Experience:

This is what we might call the historical duty argument. It runs as follows: Irish people have been (and still are) immigrants elsewhere. Therefore today they should empathize, and treat others in that position with respect and welcome […]. Thus, in this logic, a moral obligation is derived from a national collective experience […]. Irish emigration stretched the notion of Ireland to include parts of the diaspora, and tacitly recognizes other people’s diasporas as legitimate spaces to be incorporated within that system.[19]

The cultural implications of this “historical duty” argument have been most fully explored by Sinéad Moynihan in her book Other People’s Diasporas: Negotiating Race in Contemporary Irish and Irish-American Culture (2013). As she notes, “the ‘historical duty’ argument became the most pervasive liberal position on immigration during the boom era.”[20] Moynihan refers to my previous publication,[21] which found, as she notes, “that the historical-duty argument is pervasive”[22] in Irish plays about migration, and that Irish theater, more than any other artistic or cultural form, “has served to provide a vehicle and a venue for […] the staging of spectacles of intercultural contact, in which interconnections between immigrant perceptions and Irish historical memory has become dramatized as a recurrent narrative conceit.”[23] Moynihan considers my suggestion that these dramatizations of Irish historical memories of migration “can at least serve to lay the groundwork for creating an imaginative space of sympathetic engagement and generating a sense of cross-cultural solidarity,”[24] although she is “less convinced of the benefits of the approach.”[25] Her critique of “historical-duty” as a vehicle of liberal empathy suggests its limitations as a dated Celtic Tiger-era aesthetic and ethical strategy; yet it did at least create an opening for immigrants and minorities on Irish stages that hitherto did not exist.

At the height of the Celtic Tiger boom in 2005, two plays about the arrival of African-American abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Sarah Worth in Famine Ireland gave theatrical expression to this “historical-duty” argument: namely, Donal O’Kelly’s The Cambria and Elizabeth Kuti’s The Sugar Wife. Both had been conceptualized, devised, and performed in the aftermath of the Irish Citizenship Referendum of June 2004, which rescinded the automatic right to Irish nationality for immigrant children born on the island of Ireland. The Cambria, in particular, has engendered considerable debate about the limitations of “historical duty” as a dramaturgical conceit. The play’s premise is that the arrival of the famous African-American abolitionist and ex-slave Frederick Douglass in Famine Ireland in 1845 prefigured that of asylum seekers and refugees one hundred and sixty years later in the era of the Celtic Tiger, whose plight inspired little sense of empathy despite the nation’s increasing prosperity. According to O’Kelly, “Douglass […] arrived in Ireland on false papers, [but] was invited to dine with the lord mayor. It’s a lot better than the reception asylum seekers receive nowadays at the hands of Ireland’s refugee laws and direct-provision system, which leaves families in limbo for years, to live in one room.”[26] The play opens with the question, what “if Frederick Douglass […] came to Ireland NOW?” It closes with the assertion that “Frederick Douglass [was a] one-time asylum-seeker and refugee.”[27]

The Cambria has proved particularly controversial because of O’Kelly’s decision to cast himself as Douglass and use a framing tale of deportation in contemporary Ireland. As Charlotte McIvor and Matthew Spangler note in Staging Intercultural Ireland:

In The Cambria, O’Kelly and [costar Sorcha] Fox embody the story of Douglass’s sea crossing shifting seamlessly, with the aid of minimal props and costumes, between a large cast of characters […]. The play begins and ends with the story of a contemporary Irish secondary school history teacher mourning the deportation of her Nigerian student, Patrick, in Dublin airport in the company of a sympathetic workman. She tells the man the story of Frederick Douglass as a gesture of hope and as a possible model for different approaches to the asylum system in Ireland today.[28]

This framing tale about a Nigerian student asylum seeker named Patrick (“who played Saint Patrick in the school pageant”) and its contrived association with the story of Frederick Douglass, as well as the spectacle of a white Irish actor impersonating Douglass while denying that he is a black-face minstrel, have made critics like Moynihan “uneasy with some aspects of the play.”[29] Moreover, as McIvor notes, the play elicits the audience’s empathy for immigrants like Patrick in the present only through “the activation of Irish memory of the past.” The implication is that “the Irish capacity for affective engagement” and notion of “historical duty” is dependent upon the past suffering of “the Other” rather than any sense of “shared circumstances or common political goals in the present.”[30]

Nevertheless, The Cambria did implicate its audience in 2005 as privileged consumers of the global north who had become oblivious to their past and historical duty to be more receptive to asylum seekers and refugees, like Douglass, in the same spirit as their ancestors. This tension between Irish historical remembrance and current experience of privilege and privation is also dramatized in Elizabeth Kuti’s play The Sugar Wife. Like The Cambria, The Sugar Wife was produced in 2005 and premised on the visit of African-American abolitionist Sarah Worth, based on the historical figure Sarah Redmond Parker, to Famine Ireland in 1850. The play also features glimpses of “hungry wretches”[31] in the development of its plotline, as the abolitionist Sarah Worth enters a Quaker household that is actively opposed to the slave trade and involved in famine relief, but also implicated in commercial and colonial networks for the importation of luxury goods like coffee, sugar, and tea from which its wealth is derived. As Kuti remarks:

The Quaker community in Dublin just after the Famine offered me a setting that was very resonant for me: an immigrant household, so the characters would have an outsider’s perspective […], but as citizens living and working in Dublin they were insiders too. […] Dublin itself was very important to the play, and Bewley’s Oriental Tea-houses in particular. […] The paradox of its simultaneous involvement in philanthropic work as well as the campaign for the abolition of slavery whilst also having trading interests in sugar, a crop so central to slavery, seemed very ripe for dramatic exploration. […] In an Irish context, the Quaker contribution to Famine relief has been widely acknowledged. The transatlantic coffin-ships carrying thousands of dispossessed Irish people were a grim echo of slave-ships that had sailed for America from Africa, bringing Africans to work on sugar plantations.[32]

Kuti goes on to state explicitly that these intersections between the Black and Green Atlantic provided her with an imaginative and mnemonic framework for exploring the cultural condition not of nineteenth-century so much as Celtic Tiger Ireland. She cites Bernard Klein’s claim that “public acts of memory define us, not them,” and elaborates that:

The Sugar Wife was a play in many ways “about” Dublin in the late twentieth, early twenty-first century that I was living in: it was inspired by the climactic roar of the Celtic Tiger that had produced pockets of astonishing affluence in the city of Dublin, right next to pockets of extreme poverty and deprivation. Irish emigration had long had a voice in the culture and the national narrative; immigration into Ireland from outside was a relatively new phenomenon […]. By 2005, Dublin had become an ethnically diverse society, and the idea of strangers coming to these shores as immigrants was becoming a part of Irish experience, even if it was not (yet) expressed in Irish culture.[33]

Thus, The Sugar Wife, like The Cambria, recreates the Irish experience of immigration in the twenty-first century aftermath of the Citizenship Referendum through its extended allusions and dramatization of nineteenth-century Famine Ireland.

Surrogation and the Irish Famine Migration

This strained analogy and staged contrivance of the “historical duty” argument in The Cambria and The Sugar Wife has been perceptively examined by Kathleen Gough in Kinship and Performance in the Black and Green Atlantic: Haptic Allegories (2014). She cites my work on immigrant reclamations of Irish cultural icons and their “experiences of intercultural contact and conflict”[34] that produce, in her phrase, “complex modes of dramaturgical surrogation in which new actors step into the traditional roles of characters, ranging from Saint Patrick to Christy Mahon in Synge’s Playboy.”[35] Moreover, Gough applies Joseph Roach’s groundbreaking concept of “surrogation” from his book Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (1996) to help develop a more exacting and supple model of the relation between cultural memory and performance than the “historical duty” argument. At the beginning of Cities of the Dead, Roach declares that:

I propose to examine how culture reproduces and recreates itself by a process that can best be described by the word surrogation. In the life of a community, the process of surrogation does not begin or end but continues as actual or perceived vacancies occur in the network of relations that constitutes the social fabric. Into the cavities created through death or other forms of departure, I hypothesize, survivors attempt to fit satisfactory alternatives. Because collective memory works selectively, imaginatively, and often perversely, surrogation rarely if ever succeeds.[36]

In other words, whereas the “historical duty” argument assumes an unproblematic model of memory based on an imputed and straightforward sense of continuity between past and present that generates feelings of empathy in the recollecting subject, Roach’s notion of surrogation places more emphasis on its artificiality, contrivances, and necessary elisions that mask the discontinuities and ruptures that occur within communal forms of remembrance. It both encompasses and complicates the ideal of historical duty in stressing that “collective memory” is often compensatory for those “cavities” and “perceived vacancies” occasioned by death, departure, and loss.

As Gough recognizes, surrogation provides a better theoretical model for interpreting the strained analogies and staged contrivances of historical resemblance between Famine and Celtic Tiger Ireland in The Cambria and The Sugar Wife than Garner’s concept of “historical duty.” She argues that “both plays reference the experiences of African women under slavery and suggest compelling analogies to contemporary debates” in Ireland about immigration, asylum, and citizenship. Gough adds that these “nineteenth-century African slave women […] serve as the dramaturgical ‘limit concept’ and as a ‘limit concept’ for the nation: they help to define what the nation and citizenship is not.”[37] Patrick Lonergan also interprets The Sugar Wife in terms of its underlying analogies between nineteenth-century slavery, global inequality, and Celtic Tiger Irish society; but, in his view, its “main theme” is “the construction of pleasure: how it is experienced, commodified, sold, reproduced, and aestheticized.”[38] Indeed, Sarah Worth’s declaration that “nothing gets done without desire”[39] implicates the audience and its leisure pursuits in perpetuating inequality as privileged consumers of the global north no less than its nineteenth-century cast. The play raises the question of whether our “whole edifice is constructed on a mountain of skulls”[40] in the present as in the past. Like The Cambria, The Sugar Wife positions its audience as the beneficiaries of globalization, neo-colonial exploitation of the global south, and the ever increasing consumption of luxury goods.

Famine Plays and the Collapse of the Celtic Tiger: DruidMurphy’s Famine

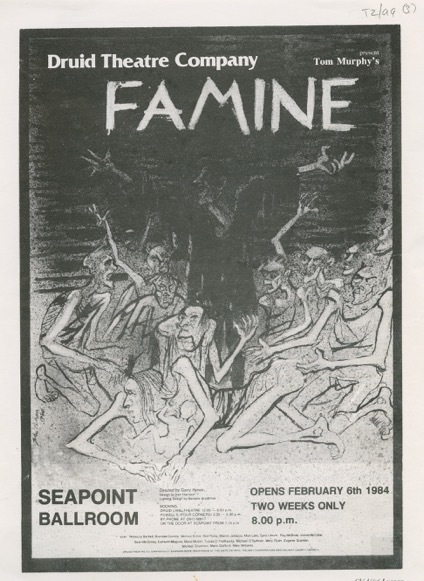

The collapse of Ireland’s Celtic Tiger economy in 2008, however, occasioned a change in register in the performance of Famine remembrance. Plays produced in the aftermath of the downturn did not implicate their audiences as beneficiaries of global inequality but rather as its sudden victims, forced to relive a legacy of surging unemployment and involuntary mass-migration no longer safely consigned to the past. It was Galway-based DruidMurphy’s 2012 revival of Tom Murphy’s play Famine (1968) that most emphatically and self-consciously signified this shift. DruidMurphy’s director Garry Hynes claims that she was inspired to remount Famine because it offered “an inner history of Ireland […] under the pressure of a debt crisis that has become an identity crisis” [… as well as] the fiercest interrogation of where nations fail.”[41] As Patrick Lonergan notes, the play “makes for sobering viewing in contemporary Ireland, as the country cuts spending on health care and education in order to bail out banks and support yet another discredited economic ideology.”[42]

Famine has been revived a number of times since it was first produced in 1968. In the play, Murphy assembles a “fearful army of spectres” that re-enacts a spectacle of scarcity and the threat of “moral force” and physical violence in a manner that draws on the performative gestures and repertoire of the 1840s.[43] Murphy himself invokes the image of the Famine procession as an amalgam of historical memory and the contemporary reality of Civil Rights marches in 1968 as the source of his inspiration. His emphasis on the movement of processions as inherently performative occasions, collective expressions of protest and privation, recurs frequently in the script. Throughout Famine, crowds assemble to deliberate about whether acquiescence or resistance to the prospect of assisted emigration and threat of eviction represent the best means of survival for their plight. The impact of the Great Hunger is registered both formally and thematically as the size of the cast diminishes on stage. The protagonist John Connor’s descent into madness and destruction of his family is marked by his immobility as “a strange isolated figure”[44] at the end of the play. Moreover, the talisman of the loaf of bread that had signified mass protest and privation in 1846 becomes for Murphy symbolic of a familial struggle for self-preservation, the sight of which precipitates his protagonist’s mental collapse.

More broadly, it was the collapse of the Celtic Tiger that made DruidMurphy’s production of Famine in 2012, according to director Garry Hynes, “particularly resonant now.”[45] The question of how Murphy’s play registers the social concerns of the 1960s as well as the downturn can be explored in a variety of ways. Murphy himself has declared that even while he was writing the play in 1968, he was not only “aware of the public event that was the Irish Famine in the 1840s” but also “drawing on […] apprehensions of myself and my own times.”[46] Nicholas Grene and Christopher Murray both contend that the play is as much about the “the Irish inheritance of famine” and its psychological legacy, its long-term consequences and impact upon the development of the Irish psyche, as the event itself.[47] As noted, Chris Morash suggested in 2008 that Famine was beginning to lose its force “in the era of the Celtic Tiger, as an entire generation are now growing up having never known high unemployment, emigration, or deprivation. Those were the very real, very immediate realities of Irish life that gave Murphy’s play its power in the 1960s.”[48] It is clearly then the resumption of emigration, high unemployment, and widespread deprivation that gave Murphy’s Famine its new resonance, as a result of the Celtic Tiger’s collapse. More specifically, it was the play’s portrayal of mass-migration as a spurious remedy for social upheaval that appeared most topical in relation to the blighted prospects of a new generation leaving Ireland in greater numbers than their predecessors. As Murphy’s character Mickeleen deliberates about whether to accept an offer of assisted emigration or resist and face the threat of convict transportation, he could have been speaking for Irish emigrant youth when he claims: “It’s all the same: Canada or Australia.”[49]

Thus, Murphy’s play has acquired new meaning since the collapse of the Celtic Tiger because it registered anxieties about the displacement of Irish families and the diminishing prospects for Irish youth, in particular, against the backdrop of the nation’s most devastating catastrophe. At the end of Famine, John Connor’s orphaned daughter Maeve offers only the faintest hope of consolation as she breaks down in tears yet expresses her resilience and steadfast resolve to survive the calamity: “There’s nothing of goodness or kindness in this world for anyone but we’ll be equal to it yet,” she declares.[50] Her predicament as a Famine orphan gradually deprived of familial and social support becomes a metaphor for Irish youth seemingly wrenched from a prosperous nation to confront reduced expectations and self-images of deprivation from the past. More precisely, it is the re-imagined plight of expendable children and superfluous youth that provided the impetus for dramatic re-enactments of the Irish Famine, not only by DruidMurphy but by a variety of community, youth, and professional theater companies as well.

Performing the Green Pacific

Since the collapse of the Celtic Tiger, there have been a number of theatrical productions that feature Famine orphans as emblematic figures for contemporary Irish youth. They include Jaki McCarrick’s play Belfast Girls, developed at the National Theatre Studio in London in 2012, and recently mounted in Chicago in 2015, and Fiona Quinn’s The Voyage of the Orphans, which was performed by the County Limerick Youth Theatre group in Lough Gur and at the Belltable in Limerick in 2009–2010, in Kilkee in 2013, and for the Irish Refugee Council in Dublin in 2014. These productions tend to be more community- and youth-oriented than performances of professional theater as such. If less renowned than DruidMurphy’s Famine, they are more participatory and offer greater potential for localized engagement with the young subjects they portray, especially in rural Ireland.

Belfast Girls and The Voyage of the Orphans dramatize the experiences of Famine orphans as they embark on voyages of assisted emigration to Australia and Canada, two of the principal destinations to which so many young people traveled during the Great Recession. Both plays were inspired by Trevor McClaughlin’s book Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Orphans in Australia[51] and rely upon contemporary press accounts of orphan girls as “professional paupers, and therefore ill-organized, diseased, and incorrigibly depraved”;[52] “the most notorious and riotous amongst these—both in transit and on arrival in Australia—were known as the Belfast girls,” notes McCarrick.[53] The stigmatization of these young women is thus emphasized to accentuate the hostility that Ireland’s most vulnerable migrants were subjected to not only at home but abroad.

McCarrick’s play is set mainly below deck and recreates the journey of the emigrant vessel Inchinnan, which sailed from Belfast to Sydney in 1850. From the beginning, the cast of five young women in Belfast Girls exchange profanities in a seemingly anachronistic modern dialect and engage in sexually boisterous antics that are gradually revealed to provide a means of self-protection from deeply damaging formative experiences in their youth. Their nominal leader is Judith, a Jamaican immigrant and prostitute who questions “how many of us have lied to get on this ship. The Belfast Girls? Half of us are public women. All known to each other.”[54] Over the course of the voyage, their collective experiences of abandonment and abuse, infanticide, and recourse to prostitution are recounted, but a series of role reversals is also enacted on stage in which the most vulnerable member of the group is revealed to be a landlord’s daughter seeking to make her own escape from Ireland and her privileged upbringing. The strategic duplicity of each of the “Belfast Girls” in feigning the role of Famine orphans as a means to emigrate enlists the audience’s sympathy for migrants past and present who arrive in a new country under false pretenses. Yet as their voyage continues, their opportunism in seeking a fresh start is also revealed to be self-defeating when they discover that even in Australia they will be subject to opprobrium, and that their reputation as stigmatized “public women” has already preceded them to the New World. “We didn’t leave Ireland at all, ladies. Ireland has spat us out,” Judith bitterly acknowledges. “If we weren’t all orphans before we left—we certainly are now!”[55] It is the play’s refusal of consolation to mark the end of their voyage that resonates most profoundly for current would-be emigrants.

The conclusion and lack of closure in The Voyage of the Orphans appears no less bleak. Like Belfast Girls, the play dramatizes the assisted emigration of Famine orphans from a workhouse in County Limerick to Australia on board the Earl Grey in 1848. The Limerick Youth Theatre production featured a much larger cast, however, and was developed from a series of workshops with young people and students in rural Limerick with funding from an EU “Youth in Action” grant. Unlike Belfast Girls, the large chorus of Famine orphans in Fiona Quinn’s play appears less individuated as characters. They are cast against a host of authority figures, such as matrons, doctors, and reverends in the institutional settings of the workhouse and on board the ship, as well as colonists and journalists in Australia. Also unlike Belfast Girls, The Voyage of the Orphans appears more naturalist in style, with characters speaking in nineteenth-century idioms and dressed in period costume, although its naturalism is continuously undercut by its non-professional young actors.

More importantly, the play is at its most powerful when it departs from naturalist convention, and its chorus of Famine orphans speaks. In the opening scene, the script indicates that they file on stage “to the sound of the workhouse six am bell. They stand in formation and recite […] facts about workhouse life.”[56] Throughout the course of the voyage, groups of characters assemble on stage to recount past experiences and deliver normative judgments about the Famine migration with their choric voice. Like Belfast Girls, the play emphasizes the stigmatization of Irish orphans in its reproduction of anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Australian press. Popular prejudice against the degenerative influence of the Famine Irish is expressed by the figure of an “Australian journalist with broadsheet, standing stage left like a candidate out on the hustings.”[57] He vehemently condemns the emigrant girls as “coarse, useless creatures,” while stage directions indicate that they “file past the hostile crowd/audience, heads lowered, jostled and jeered.”

Ultimately, the historical plight of these young female emigrants is imaginatively and seamlessly merged with that of separated children in modern Ireland in the play’s final scene, which once again is signaled by a departure from naturalist convention. At the end of the play, stage directions indicate that the “Girls all enter in non-naturalistic formation” and “recite the facts of orphan immigrant lives”:

* Immigrant: Alice Ball, teenager, seduced by married employer, destitute and pregnant, suicide by drowning April 1850 […]

* Immigrant: Kosiwa Abuyu, 12, discovered by Gardai in Co. Louth after being trafficked to Ireland, held captive and inducted into sex slavery. 2005 […]

* Immigrant: Sahar Deghani, teenager, seduced by married employer, destitute with infant 2008

All: Immigration—orphans—separated children. This is not a story of the past, it is the ongoing story of the world.[58]

Thus declares the chorus in the final line of the play. It is a “story of the past [that] is offered clearly as a political catalyst,” notes McIvor, one “whose power is awakened by the retreading of emigrant histories to educate and perhaps to shame, a hailing that may not always be comfortable.”[59] Indeed, what discomfits the audience is being implicated as members of the Irish host society in contemporary acts of female migrant exploitation no longer consigned to the past. The play recasts female immigrants as emigrant orphans whose experiences of sexual violence become registered through the “surrogated performance” of Irish migrant predecessors. The implication is that vulnerable immigrants can only “be seen as Irish through the lens of Irish history rather than within the context of their own stories and evolving identities.”[60] Even so, the play’s youthful, multiethnic cast had a significant role in devising the performance, which is more participatory than most of the works discussed here. The end of The Voyage of the Orphans offers no more sense of consolation than Belfast Girls, but its emphasis is less on the futility of mass migration than the plight of separated children.

Beyond “Historical Duty”

In conclusion, the suggestion that the memory of the Famine migration “is not a story of the past” provides the underlying premise for all of the theater productions about the Great Hunger during the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger. These plays create palimpsestic scenarios that over-layer the memory of the 1840s on plotlines of migration in the present. Whether their performance of Famine remembrance is modeled on the ideal of “historical duty” or the more awkward mnemonic contrivances and elisions of surrogation, their dramatization of Irish historical memories of migration imaginatively situates and stages the figure of the immigrant in contemporary Ireland against the backdrop of the Famine exodus, with all of the limitations of perspective this entails. Yet there has been a significant shift from plays like The Cambria and The Sugar Wife, which implicate their Celtic Tiger–era audiences as beneficiaries of globalization, neo-colonial exploitation, and ever increasing consumption of luxury goods, to these more recent works that cast actual migrants alongside vulnerable Irish young people who have been forced to relive a legacy of economic calamity and involuntary migration. There is a real poignancy in youth theater actors, in particular, performing the spectacle of their own displacement before their families, friends, and parents, as a not unlikely premonition of their fate. Ultimately, the performance of Famine remembrance in plays produced during the rise and fall of the Celtic Tiger brings together past and present storylines of mass migration from Ireland, alongside reminiscences of immigrant arrivals, into the same dramaturgical frame. Their emphasis on the “historical duty” of Irish audiences to feel empathy for their immigrant subjects has become a dated aesthetic strategy; but the latter plays are more participatory in their casting and concern with vulnerable migrant youth.

The next generation of productions about the Great Hunger is shifting to more generically innovative works like the Moonfish Theatre’s bilingual adaptation of Joseph O’Connor’s novel Star of the Sea (2002) and Donnacha Dennehy’s opera The Hunger (2016). It remains an open question whether the theme of eviction will become more prominent in future plays, as Ireland’s economic recovery has yet to alleviate its ongoing property crisis and rising levels of homelessness. The current trend, though, is for adaptations such as Moonfish’s Star of the Sea, which was performed mostly in Irish, with scrolling English subtitles, at the Galway International Arts Festival in 2014 and the Dublin Theatre Festival in 2015, and was well received by non-Irish-speaking audiences. Even more ambitious is Dennehy’s opera, which was performed at the Kennedy Center, in Washington, DC, in 2016. It is based on the travels of an American, Asenath Nicholson, through Famine Ireland, where she encountered scenes like this: “a pitiful old man in hunger and tatters with a child on his back, almost entirely naked, and to appearance in the last stages of starvation.”[61] Dennehy aspires to recover the Gaelic-speaking majority’s “musical culture” that “almost shut down entirely through the period” as a result of what “the renowned 19th-century song-collector George Petrie” termed “a great unwonted silence.” Dennehy turns to the sean nós tradition of unaccompanied singing and extended “shards of that song,” the “Na Prátaí Dubha” (Black Potatoes), to help recuperate this lost musical culture. The opera’s libretto also features contemporary critics and economists, such as Maureen Murphy and Paul Krugman, in dialogue with Asenath Nicholson and the opera’s underlying theme of “the conflict between the responsibilities of governance versus a strict philosophy of not interfering with the mechanism of the market.”[62] The opera is also more expansive in its perspective on global inequality, with less emphasis on Ireland than world hunger in the era of economic collapse. Krugman’s remark that “the big problem with charity is it’s almost never enough […] to seriously alleviate poverty on an ongoing basis” is addressed to the policy makers of the present rather than the past.[63] The Hunger received mixed reviews for its generic experimentation;[64] but the more pressing question of whether the musical culture of Famine Ireland can be recovered from Petrie’s “great unwonted silence” remains unexplored. Even so, both The Hunger and Moonfish’s adaptation of Star of the Sea signify a new, generically striking approach to staging the Great Hunger, one that moves beyond the era of the Celtic Tiger and its collapse.

[1] Jan Assmann, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity,” New German Critique 65 (1995): 129.

[2] Steve Garner, Racism in the Irish Experience (London: Pluto, 2004), 159; Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 2.

[3] Charlotte McIvor, Migration and Performance in Contemporary Ireland: Towards a New Interculturalism (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 118. For the passage quoted by McIvor, see Jason King, “Interculturalism and Irish Theatre: The Portrayal of Immigrants on the Irish Stage,” Irish Review 33 (Spring 2005): 24.

[4] Ibid., 123.

[5] Ibid., 115–52.

[6] Dawn Williams, “Nathaniel Grogan, Whipping the Herring Out of Town,” in A Question of Attribution: The Arcadian Landscapes of Nathaniel Grogan and John Butts (Cork: Crawford Art Gallery, 2012), 148; see also http://www.crawfordartgallery.ie/pages/paintings/Grogan_Herring.html.

[7] Pictorial Times, October 10, 1846.

[8] Ciarán Ó Murchadha, The Great Famine: Ireland’s Agony, 1845–1852 (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 41.

[9] Relief Commission Papers, 3/1, 1819, National Archives of Ireland. Reproduced in Kevin Hourihan, “The Cities and Towns of Ireland, 1841–1851,” in Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, ed. John Crowley, William J. Smyth, and Mike Murphy (Cork: Cork University Press, 2012), 231.

[10] Cork Examiner, September 4, 1846.

[11] Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003), 20.

[12] Christopher Morash, “‘…How Feeble and Inexpressible is the Word!’: Staging the Irish Famine,” in Hunger on Stage, ed. Elizabeth Angel-Perez and Alexandra Poulain (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2008), 138.

[13] Ibid., 138.

[14] Christopher Morash, “Sinking Down Into the Dark: The Famine on Stage,” Bullán 3, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 84.

[15] Morash, “How Feeble,” 146–47.

[16] See Jason King, “Staging Famine Irish Memories of Migration and National Performance in Ireland and Québec,” CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 18.4 (2016), accessed January 11, 2018, https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2907.

[17] Garner, Racism in the Irish Experience, 159.

[18] Steve Garner, Whiteness: An Introduction (Abingdon: Routledge, 2001), 142.

[19] Garner, Racism in the Irish Experience, 159–60.

[20] Sinéad Moynihan, Other People’s Diasporas: Negotiating Race in Contemporary Irish and Irish-American Culture (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2013), 19.

[21] King, “Interculturalism and Irish Theatre.”

[22] Moynihan, Other People’s Diasporas, 100.

[23] King, “Interculturalism and Irish Theatre,” 24.

[24] Jason King, “Remembering and Forgetting Diaspora: Immigrant Voices and Irish Historical Memories of Migration,” in Rethinking Diasporas: Hidden Narratives and Imagined Borders, ed. Aoileann Ní Éigeartaigh, Kevin Howard, and David Getty (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2007), 61.

[25] Moynihan, Other People’s Diasporas, 101–2.

[26] Donal O’Kelly, “Sharp Lessons for Contemporary Campaigners: Frederick Douglass in Ireland by Laurence Fenton,” Irish Times, May 10, 2014, accessed April 2, 2017, http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/sharp-lessons-for-contemporary-campaigners-frederick-douglass-in-ireland-by-laurence-fenton-1.1786900.

[27] Donal O’Kelly, The Cambria, in Staging Intercultural Ireland: New Plays and Practitioner Perspectives, ed. Charlotte McIvor and Matthew Spangler (Cork: Cork University Press, 2014), 160, 196.

[28] McIvor and Spangler, Staging Intercultural Ireland, 155.

[29] Ibid., 159, 129.

[30] McIvor, Migration and Performance,133.

[31] Elizabeth Kuti, The Sugar Wife (London: Nick Hern Books, 2005), 18.

[32] Elizabeth Kuti, “‘Strangeness Made Sense’: Reflections on Being a Non-Irish Irish Playwright,” in Irish Drama: Local and Global Perspectives, ed. Nicolas Grene and Patrick Lonergan (Dublin: Carysfort Press, 2012), 152.

[33] Ibid., 153–54.

[34] King, “Interculturalism and Irish Theatre,” 25.

[35] Kathleen Gough, Kinship and Performance in the Black and Green Atlantic: Haptic Allegories (New York: Routledge, 2014), 159.

[36] Roach, Cities of the Dead, 2.

[37] Gough, Kinship, 160.

[38] Patrick Lonergan, Theatre and Globalization: Irish Drama in the Celtic Tiger Era (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008), 208.

[39] Kuti, The Sugar Wife, 77.

[40] Ibid., 54.

[41] Garry Hynes, “Director’s Note,” in DruidMurphy: Plays by Tom Murphy, by Tom Murphy (London: Methuen 2012), xvii.

[42] Patrick Lonergan, introduction to DruidMurphy: Plays by Tom Murphy, by Tom Murphy (London: Methuen 2012), xiii–xiv.

[43] Tom Murphy, Famine, in Plays: 1 (London: Methuen, 1992), 64, 20–30.

[44] Ibid., 89.

[45] Or, at least, this is what Siggins reports Hynes to have stated; see Lorna Siggins, “Devil’s in the Detail at Druid Rehearsals,” Irish Times, May 31, 2012, accessed April 2, 2017, http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/stage/devil-s-in-the-detail-at-druid-rehearsals-1.525161.

[46] Tom Murphy, introduction to Plays: 1 (London: Methuen, 1992), xiv.

[47] Nicholas Grene, The Politics of Irish Drama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 237; Christopher Murray, Twentieth-Century Irish Drama: Mirror Up to Nation (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 183–84.

[48] Morash, “How Feeble,” 146–47.

[49] Murphy, Famine, 75.

[50] Ibid., 89.

[51] Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Orphans in Australia (Melbourne: Genealogical Society of Victoria, 1991).

[52] Fiona Quinn, The Voyage of the Orphans (unpublished play, County Limerick Youth Theatre, Limerick, 2009), 73.

[53] Jaki McCarrick, author’s note in Belfast Girls (London: Samuel French, 2015).

[54] McCarrick, Belfast Girls, 67–68.

[55] Ibid., 86.

[56] Quinn, The Voyage, 3.

[57] Ibid., 47.

[58] Ibid., 69–70.

[59] McIvor, Migration and Performance, 124.

[60] Ibid., 125, 124.

[61] Program for The Hunger (Brooklyn Academic of Music, 2016), 9, accessed April 2, 2017, https://www.bam.org/media/7345758/The_Hunger.pdf.

[62] Ibid., 3.

[63] Ibid., 11.

[64] See Corinna da Fonseca-Wollheim, “Review: An Unsatisfying Opera (or Is It a Lecture?),” New York Times, October 3, 2016, accessed April 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/04/arts/music/review-donnacha-dennehy-the-hunger-opera-bam-next-wave-festival.html?_r=0; see also Anne Midgette’s more positive review, “Opera ‘The Hunger’ Offers an Austere, Earnest Thesis on World History,” Washington Post, June 2, 2016, accessed April 2, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/music/opera-the-hunger-offers-an-austere-earnest-thesis-on-european-history/2016/06/02/0756338c-28f0-11e6-b989-4e5479715b54_story.html?utm_term=.0e960ff73d3a.