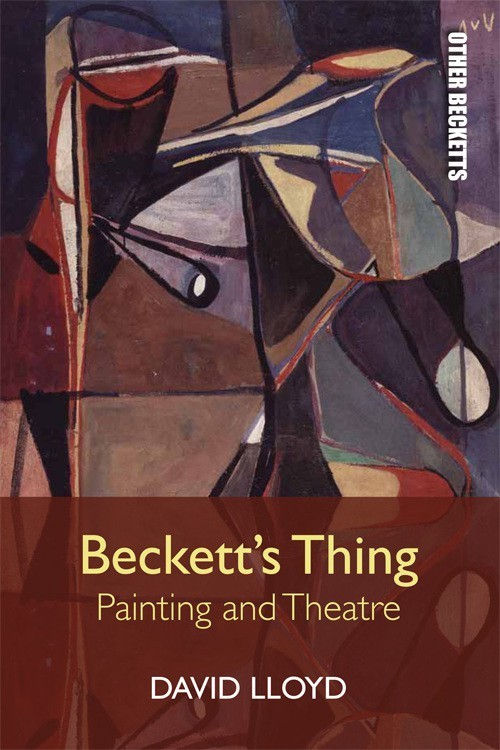

David Lloyd. Beckett’s Thing: Painting and Theatre. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016, xiii + 253 pp.

With patience and lucidity, David Lloyd’s Beckett’s Thing: Painting and Theatre devotes a long chapter each to the works of three painters whom Samuel Beckett admired intently: Jack B. Yeats, Bram Van Velde, and Avigdor Arikha. Lloyd’s slow readings of the paintings almost stand alone, confident beside the stunning reproductions cataloged amid them. Each chapter, it is true, concludes with illuminating pages on the visual aesthetic of Beckett’s late theater, learned from or shared with these painters. But the weight is on the individual artists. As literary criticism, this balance could appear misbalanced. Instead, it should be understood as Lloyd’s corrective, a formal argument against literary criticism he finds too quick to understand Beckett’s engagement with visual art as allusion only; too quick to seek meaning in verbal content, symbol, or allegory rather than coming to terms with the formal, visual disruption of significance; too quick to overlook how Beckett’s “visual principles” develop in front of, and in kinship with, specific paintings. This meditative approach to visual form is masterful and illuminating. It reveals how deeply into the staging of later drama Beckett disorients the audience’s subject position and calls into question “the relations of domination that are inscribed in its possessive subject-object relations” (13). By keeping our focus here, by holding us for pages and pages in the deep immersion of an aesthetic experience, by gripping us with the power dynamics inherent in the gaze, Lloyd prepares Beckett’s repudiation of “representation as an aesthetic and political category,” at once demoting meaning found in language and content, even as Lloyd resurrects significance in the function of visual form. This demotion also has its costs, and I will reflect on them later. First, let me elaborate its argumentative bounty.

Beckett is drawn to Yeats, van Velde, and Arikha because each, in their own idiosyncratic way, interrogates the ethics of how a visual aesthetic functions. By “ethics,” Lloyd means in part the consequence of challenging the power dynamics involved in viewing itself. Think of perspectival painting sourced in the Renaissance, whose checkerboard technique rewards the viewer with a geometry of knowing, fashioned to the viewer’s vantage and confident subject position. Then consider its disruption. The ethical stakes are given philosophically as well. Beckett’s “thing” in Lloyd’s title refers to Beckett’s lifelong obsession with painting—his thang as we say in Alabama. More exactly, though, it signals Beckett’s concern, found in Beckett’s own criticism, with the object as it is before representation, before, that is, words or painting necessarily impose conceptual understanding on it, concepts that make cognition possible, but formally “possess” the objects depicted.

Other thinkers contemplate this thingness of a thing. Lloyd remembers Heidegger’s essays. Whereas Heidegger nostalgically identifies the thing “with the pre-commodity, artisanal object,” Beckett, Lloyd argues, moves beyond this ahistorical conception and avoids such romantic compensation, sensitive as Beckett is to “an increasingly instrumentalized economic and political world” (19). Beckett was drawn, then, to artists who resist or make known representation’s complicity in attitudes of possession or artists who preserve this stubborn thingness, thereby insisting on an aspect of humanity unavailable to representation. More, by dislocating visual aesthetics in his own later work, Beckett applies these lessons: “Beckett’s late plays thus deny the audience the position of spectator that is the theatrical equivalent of the punctual perspective which secured the subject its sovereign position in the possessive spatial relations of Western art” (21).

So Jack B. Yeats’s paintings, with their “belligerent orneriness…refuse to resolve to the viewer’s gaze” (28). This formal “resistance” has a political corollary, formulated by Lloyd as a “principle of non-domination,” or more specifically a refusal, here named “republican,” to accept the disappointingly limited Irish Free State as is. Not that both Jack B. and Beckett advocate for Irish republicanism explicitly. They don’t. But for both, the ethic of representation has its corollary in refusing representations of an idealistic nationalism: the “internal dynamics by which figure and ground, material and image, technique and content are held in suspended, oscillating equilibrium correlates to a refusal of domination that is the aesthetic counterpart of a radical republicanism” (66). The “ruin of representation…follows in the wake of the national project” (67).

Similarly, Bram van Velde leaves the eye “in a state of radical uncertainty as to where to settle, as to where its gaze should fix” (110). Van Velde’s non-figurative painting resists how representation appropriates the object and, in Beckett’s estimation, somehow suspends the object to reveal “‘the visible thing, the pure object’” (120). This is not about knowing things better through painting, nor experiencing pure aesthetic form, as might be said of abstract expressionism. Rather, what Beckett intuits in van Velde is an attempt to dismantle the “subject-object relation that grounds the aesthetic judgment in the first place” (132). Lloyd shows, in particularly fine pages, how, for Beckett, this need to dismantle the foundations of Western aesthetics after World War II pits him against French art critics associated with Transition, in particular Beckett’s friend Georges Duthuit. They imagined a reconciliatory role for postwar aesthetics, “redemptive and utopian demands” that Beckett parodies in Three Dialogues. Whereas van Velde destroys the pictorial space and the image, Beckett systematically sunders the “gaze, figure or subject, and voice” in Play, Film, and Eh Joe. The subject is dispersed “into multiple things, technical and corporeal, that constitute it and its relations with objects” (136). The voice and gaze are not “media of expression or seeing,” not about self-perception, but rather things in which the “subject is dispersed” (139). The crisis in the subject performed this way reflects the era of late capitalism.

As art criticism, Lloyd’s study of Arikha is of a very high order, penetratingly rich in its detailed readings of paintings and drawings. Here, more than in the other chapters, the relationship between the painter and writer is that of analogy. Arikha goes through a profound aesthetic crisis, analyzed as an urgent need to unlearn the mastery of modern representational practice and manifested when he abandons abstract painting completely for black and white, charcoal or ink. He learns to draw what he observes, a reckoning that matures all of his work thereafter into a relentless interrogation of “what it is to see” (157). For Lloyd, Beckett’s turn to French is a similar crisis, his seeking better ways to undo what he has learned, expressed (again) as dismantling the munificence of Joycean technique and signification. And like Arikha’s paintings, Beckett’s later plays examine visibility itself. They challenge a Western aesthetic tradition, not in the meanings of plays which are sometimes banal—the adultery plot line of Play, say—but on the level of the audience’s visual experience, the happening as the thing itself. What Lloyd sees in the late plays is an attempt to destroy theater, to “dismantl[e]…the regime of representation” to fracture “not only the aesthetic but with it the political and ethical dimensions through which the modern subject is articulated” (233).

Lloyd’s book, then, posits a Beckettian politics at the level of form—a conviction that the recalcitrance and negativity in these enactments of the end of art (or Western forms of art), perform non-domination as an aesthetic logic. This political argument has force, and the insight it provides into Beckett’s later theater is convincing and needed. Adopting a formal visual approach, however, can keep politics generalized, positioned against enlightenment logics of control, on a par with Beckett’s own language of “humanity in ruins” (234). Beckett operates on this level, certainly, and keeping it here Lloyd wisely avoids the optimistic humanism of so much Beckett criticism. Yet understanding theater as painting, or understanding Beckett’s politics as broadly anti-enlightenment can also sideline the fundamental ways that Beckett writes against very specific historical and political rhetorics, markers, and events; how his works reinterpret one another in series; more, how Beckett’s theater simultaneously satirizes existentialist interpretations that present suffering as universal, as “our collective catastrophe” (234), rather than targeted and specific. This interpretative self-questioning is also central to Beckett’s work and ethic. Sometimes Lloyd takes sides instead: “what fascinated [Beckett] was not what Krapp could relate or recall, but his movement as a figure across the space of the stage, his coming and goings” (205); or with interpretations of Endgame: “there are more than enough and probably little could be added by way of original contributions” (73). Lloyd takes Beckett’s “make sense who may” as repudiation of the attempt, rather than also as an injunction to experience the failure and to recognize the specific targets of that failure (228). The difference matters. It matters too for understanding Beckett’s political aesthetic. Still, against such a terrific book, these critiques might come across like quibbling, the reviewer doing what reviewers are liable to do: to wonder why this particular book that they don’t have the skills to write is not more like the one they did. Besides, this review fails to capture what cannot be summarized: the rich close readings of superb paintings that demonstrate by their performance both the power of the aesthetic experience and what it is to see.