![]()

Seamus Heaney: Five Fables. Touchpress Limited, 2014, iPad app.

As one of the last projects before his death in August 2013, Seamus Heaney completed work on the iPad app Five Fables, produced by Touchpress, the same company behind the acclaimed Waste Land app. Five Fables is based on Heaney’s previously published joint translations of the fifteenth-century Scottish poet, scholar, and schoolmaster Robert Henryson’s The Testament of Cresseid and Morall Fabillis, the latter of which contain versions of Aesop’s fables. Heaney’s full translation, The Testament of Cresseid and Seven Fables, was published in print by Faber and Faber in 2010, and the fables selected for the app include “The Two Mice,” “The Lion and the Mouse,” “The Preaching of the Swallow,” “The Fox, the Wolf and the Carter,” and “The Fox, the Wolf and the Farmer.” These fables are the same ones included in an earlier animation project, Five Fables, commissioned by BBC Northern Ireland and produced by Flickerpix Animations studio. These fables cover what Heaney calls “some of the fiercest allegories of human existence,” as Heaney notes on “The Preaching of the Swallow” in his introduction to both the app and the translation, as well as Henryson’s “gentlest presentations of decency in civic and domestic life” (“The Two Mice” and “The Lion and the Mouse”).

Heaney’s written introduction to the tales for the app, a slightly shortened and edited version of his introduction to the printed Faber edition of his translation, demonstrates that same quality of subtlety, affective appeal, and ease with language that anyone familiar with his prose writing and criticism would be accustomed to. In recounting Henryson’s characteristic mixture of “high-toned earnestness” and “wily familiarity” in his story-telling, or “the eternal present of the perfectly pitched” and the Frostian “sound of sense” in his verse, Heaney uses descriptors that could equally characterize Heaney’s own writing. One has the sense of witnessing a meeting of two kindred minds across a historical gap of more than five hundred years.

Of the various elements included in the app, its most engaging part is no doubt the audiovisual experience of the animations, with Connolly’s performance perfectly matching the melodious diction of Heaney’s writing. Heaney’s role as a poet-translator gives the app a certain gravitas (and, no doubt, marketability) and is likely to appeal to an audience familiar with the poet’s previous work and reputation, within and beyond the scholarly community. Yet Heaney’s persona, even in his recorded introductions to the translations and individual stories, at no point seeks to upstage the fables themselves or their Scottish rhymer. And while it is Heaney’s authorship of this latest translation of Henryson’s text that motivates the energies of the app, the project is also very much a collaborative undertaking, not only in its technical production, but also in its content. Scholars, including Sally Mapstone, Bernard O’Donoghue, Chris Jones, and Gail McConnell, cover different aspects of both Henryson's and Heaney's work in short interviews. The academic notes for the application are also written by Jones, an authority on medieval poetry who has previously published on Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, while the soundtrack is the work of the composer Barry Douglas, the winner of the 1986 Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition. A quick overview of the credits section of the app will give a good idea of the caliber of collective effort such a production requires. The choice of the comedian and actor Billy Connolly as the reader for the animations was, according to Heaney, based on his “[capability] of combining the […] popular with the rather more elite” (“Introduction”). Yet Connolly’s Scottish accent no doubt resonates with that same “hidden Scotland” in the poet’s Ulster background that Heaney first recognized in Henryson’s writing (“Introduction”). The original Scots version of Henryson’s work is also read on the app by Ian Johnson, an authority on medieval literature.

Touchpress’s work in developing the app is particularly successful when one considers not only the number of individuals involved in its production, but also the variety of media for which its various elements have been created. The original fables, Henryson’s 15th century text, Heaney’s translations and the animations were all originally intended for different modes for dissemination. Though this level of modal diversity is obviously not exceptional when it comes to literary apps, something particularly suitable arises in such a digital medium for the rendition of a literary work that owes its very existence to the transmission, in various oral and printed forms, of a series of communal narratives with their roots in the European folk tradition. As Heaney himself notes, Henryson’s Fables owe their existence to the “common oral culture of Europe.”

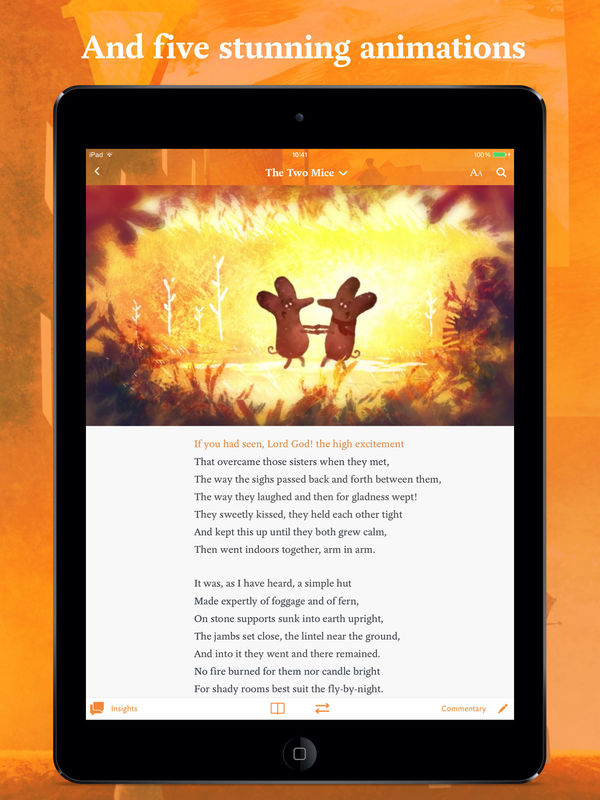

The scrolling text of the fable verses on its own or below the animation does not even attempt to replicate a book page, but its synchronized movement follows the reader’s pace (either Connolly’s or Johnson’s, or, if one wishes to use the touchscreen to scroll backward or forward, the viewer’s), with each spoken line marked in green. The app is well-executed and sleek, yet without being gimmickry for its own sake, in a manner suitable, perhaps, for a digital production of work endorsed by Faber and Faber. The nearly seamless flow of Connolly’s reading in English (and Johnson’s in Scots), the visual narrative of the animation, and the story unfolding in the text below sacrifice none of the subtleties of the oral/aural, visual, and textual modes. The split-screen view of the animation and the text also make it possible for readers and viewers of different ages and backgrounds to make the most of the experience simultaneously—rarely does an app engage both a working parent and a four-year-old so effortlessly. Perhaps the only design element to find fault with is that the desirable link to “Insights” is too apologetically placed to the lower left hand side of the screen, visible only when the reader has already navigated to one of the fables. Those interested in the scholarly commentary are likely to first look for such material in which the poet’s own introduction and other paratextual elements of the app are to be found, especially since such comments are not specific to each fable. Flickerpix’s animations are a pleasure to watch, as well. The Belfast, Northern Ireland-based company has produced animations since 2003 for CBBC, Channel 4, Sesame Street USA, Discovery, RTÉ, ABC, and the Berlin International Film Festival, as well as BBC One’s big events, Comic Relief and Children in Need. The animations also occasionally underline the coexistence of the present and the past through sly details. In “The Two Mice,” the pastoral nostalgia of the country mouse’s domicile is contrasted with the city with double decker buses; in “The Lion and the Mouse,” the poet’s encounter with Aesop with his cape and quill is followed by a mouse cheering with a giant foam hand with “#1” printed on it. The animations, like the fables themselves, are thus set in a storybook time of no specific context.

Flickerpix series producer and director David Cumming says he was particularly drawn to the potential of the app to be used for entertainment, as well as as an educational aid or a “rich academic tool.”[1] The educational aspirations of the makers of the app might appear to be in tune with the perception of the fables as didactic and morally enlightening. However, translator Laura Gibbs of Aesop’s Fables stresses that these stories were not, in their original context of Aesop’s Greece and Phaedrus’s Rome, aimed at children, but “told by and for adults,” and their didactic function is a later development. Thus, Heaney’s translation into modern English joins a long line of poets taking up the task of versifying Aesop; according to Gibbs, the moving of the fables from oral to written culture led to their being adopted by poets developing their skills in verbal craft; they were used for the “teaching purposes of grammarians and rhetoricians.”[2] Yet with his own translation, Heaney himself sought less to impress his professional literary or scholarly peers than to bring Henryson’s fables to a wider audience. While he admits that Henryson’s Scots is accessible enough for those wishing to make the effort of plowing through the original text, “people who are neither students nor practicing poets are unlikely to make such a deliberate effort” (“Introduction”). Publishing the Fables as an iPad app is thus faithful to the poet’s intent of broadening the readership of Henryson’s work. The format is perhaps not revolutionary enough to justify David Cumming’s ambitious claim of using “new technology to enrich a poetry-reading experience” to do “something new with poetry that hadn’t been done before.” [3] As far as literary apps or digital literary works go, Five Fables may not stem from the more adventurous end of the spectrum. Yet this is also one of its strengths, and the app admirably fulfills its role as an audiovisual, mobile remediation of a poetic text and its manifold versions.

Claire Lynch, commenting on Heaney's by-now famous last words, “Noli Timere,” transmitted by text message and then rapidly spread through social media across the globe, notes, “the apparent contrast between the new technology of the mobile phone and Heaney's ‘beloved Latin’ [pays] homage to the past while retaining faith in the future.”[4] Five Fables draws its strength from this same juxtaposition of modalities. While making use of the potential of new digital technologies, the app participates in the age-old transmission of culture in preserving the tradition of fables, making them accessible through not only Heaney's translations, but also the insights of those familiar with their original social, historical and cultural background in a once-bygone, but now newly re-invoked, time.

[1] Matthew Coyle, “Five Fables App Launches,” Culture Northern Ireland, accessed July 27, 2015, http://www.culturenorthernireland.org/features/literature/seamus-heaneys-five-fables-app-launches.

[2] Laura Gibbs, introduction to Aesop’s Fables, trans. and ed. Laura Gibbs (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), xi.

[3] Coyle, “Five Fables App Launches.”

[4] Claire Lynch, Cyber Ireland: Text, Image, Culture (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 1.